Reassessing the dollar’s global status

Since the end of World War II, the United States dollar has reigned as the global currency par excellence. The 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement anchored all major currencies to the dollar, which in turn was tethered to gold. However, gold was not particularly convertible, and the ceremonial link between the dollar and gold served primarily to assert that the dollar could not be manipulated and that Western economies would be based on sound money.

History has proven this to be an illusion. The gold exchange standard turned out to be deceptive; the dollar was indeed manipulated (that is, inflated) and continuously lost purchasing power. In fact, from 1960 to 1971, the dollar lost 25 percent of its purchasing power. The collapse of the Bretton Woods System in 1971 merely acknowledged the prevailing reality: the connection to gold was a sham. By 1973, all central banks declared themselves free to manipulate their currencies. As a result, between 1971 and 2023, the dollar depreciated by 87 percent.

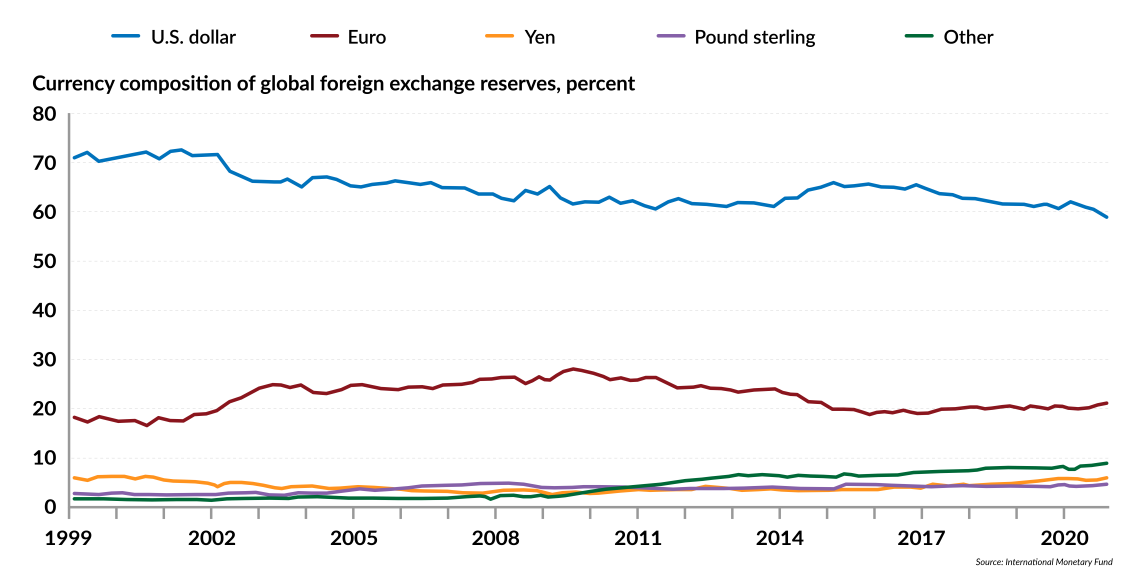

The dollar has nevertheless maintained its dominant global position. In the 1970s, inertia probably contributed to this privileged status. But it soon became clear that its role was firmly grounded in the U.S.’s prominence in global trade and capital markets, and possibly also in the fear that rival currencies would be subject to even more unpredictable monetary policies than the dollar. Unsurprisingly, at the beginning of this century, the dollar accounted for over 70 percent of the world’s foreign-currency reserves.

Looking for alternatives

In recent years, two factors have cast doubt on the dollar’s reign, and its share in global foreign currency reserves has diminished. First, the dollar’s purchasing power continues to erode. This is not a significant issue when inflation remains low and dollar-denominated assets yield positive real returns – that is when the interest rate on Treasury bonds offsets the loss of purchasing power.

Yet holding liquid dollar-denominated assets becomes problematic if doing so incurs substantial losses due to inflation. In fairness, other currencies have not performed much better. The dollar exchange-rate index shows that the dollar has outpaced a basket of traditionally reputable currencies (the euro, the yen and the British pound, which together make up over 84 percent of the reference basket). But dollar-denominated asset holders are not particularly satisfied, and they are keen to find one or more viable alternatives.

This leads us to our second point: other currencies have indeed emerged as credible competitors. Recent research by the International Monetary Fund suggests that the Australian and Canadian dollars, the Swedish krona and the South Korean won have expanded their share in global foreign currency reserves. These currencies account for a substantial portion of the shift away from the U.S. dollar. Do they a have future? Will their success encourage imitators?

The data paints a mixed picture. The dollar’s share has declined from over 70 percent in 2000 to roughly 60 percent today. Contrary to many predictions, however, the euro’s share has remained fairly stable at around 20 percent. The shares of the Japanese yen and the British pound have also held steady at about 5 percent each. The remaining 10 percent share includes the new competitors.

Chinese yuan

Contrary to much of the prevailing narrative, the Chinese yuan plays a relatively minor role, accounting for less than 3 percent of the total – not what one might expect given China’s status as a crucial player in global trade flows. The yuan’s significance may rise in tandem with China’s growing role as a trading partner and its influence in setting import and export prices. Yet, the international financial community, including central bankers, seems uneasy about keeping yuan in their vaults.

The yuan is not necessarily a strong currency compared to others; its exchange rate against the dollar and the euro has remained relatively stable over the past five years. Many market participants are wary of the possibility that Chinese authorities could intervene with heavy-handed manipulation, perhaps clamping down on convertibility. The current interest rates on China’s government bonds are not particularly attractive (2.7 percent for the 10-year bond and 2.1 percent for the two-year bond), and the issuer is not regarded as top-tier (rated A+ by Standard & Poor’s).

The fundamentals explain why. The main drivers of global currency status are the size of the currency area, the extent of government debt and international trade and the quality of the central bank backing it.

Facts & figures

Demand for top currencies by central banks

Country size matters for one major reason: those who frequently transact in global currencies want their trades to not disrupt the monetary equilibrium of the global currency. In other words, those who hoard reserve currencies want to be price-takers and deal with a relatively stable exchange rate. No one wants their sale or purchase of a global currency to precipitate a decline or increase in its purchasing power. Similarly, no one wants to hold foreign currency reserves whose purchasing power is subject to the whims of third parties.

Contender status

A global currency necessarily comes from an economy with a large gross domestic product (GDP), since larger GDPs typically coincide with more substantial money supplies. Today, and for the foreseeable future, only three monetary areas are large enough to sustain a global currency: the U.S., China and the eurozone. Russia has never been a viable alternative, and India will likely need at least a decade to build enough weight in terms of GDP and international trade flows.

Public debt is also relevant. A large share of foreign-currency reserves is not held in cash but in highly rated government bonds. In line with the price-taking principle, buyers typically prefer to purchase securities that enjoy a broad market, one not significantly influenced by individual buy or sell decisions. In this light, large debtors are rather attractive.

The world has to settle for the least objectionable option rather than the ideal.

However, these large debtors must also be of high quality. A central bank holding vast amounts of euro-denominated treasuries cannot afford the risk of France or Germany defaulting, or asking for debt rescheduling or restructuring. The ideal currencies should be issued by large, moderately indebted countries that are fully integrated into the global capital markets. China is less than ideal in this respect.

The reputation of central banking is the last item on the checklist. This factor relates to the manipulation of money and credit (interest rates). Monetary profligacy ultimately leads to inflation and affects the quality of reserves as a store of purchasing power. Similarly, meddling with interest rates affects the price of securities, which again, affects the reserves’ ability to preserve their purchasing power. Over the past decades, all major banks that aspired to achieve global currency status have failed.

Scenarios

The world economy does not currently offer a viable global currency. This is perhaps inevitable, since we live in a world characterized by paper money and heavily regulated finance and banking. Consequently, any reserve currency is vulnerable to manipulation by policymakers, often motivated by questionable or shortsighted agendas.

Central bankers are certainly eager to see their currencies acquire global currency status, since the issuing country effectively exchanges (intrinsically worthless) paper money to the world for goods and services. Yet, all potential candidates satisfy just one or two of the above criteria. The world has to settle for the least objectionable option rather than the ideal. It appears that the privileged position of the dollar is not really threatened. Inertia matters, and any successful competitor must show up with more credibility than the Federal Reserve.

This is not the case for the euro or the renminbi. The dollar has certainly lost some of its appeal, largely due to ineffective central banking and excessive regulation. Nonetheless, global central bankers’ recent attempts to diversify risk have been limited, and have favored currencies like the Australian dollar and the South Korean won, which are closely tied to the dollar and are unlikely to significantly increase their market share.

This material was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/dollar-global-status/