How tariffs will shape inflation

In early 2025, inflation was about 2.8 percent both in the European Union and in the United States, barely making headlines. Until mid-March, most commentators were predicting that in the following months the figure would drop further to about 2.5 percent. Everything seemed to be under control. Very few noted that the rates were largely where they were two years ago once consumer prices started receding from the peaks seen in 2022. While the official 2 percent target is perhaps now in sight, it will not be reached soon. In fact, it could go north before long.

In recent years, central bankers have rendered the inflation target all but irrelevant. Public opinion does not pay much attention to how fast prices rise in general, but rather focuses on specific items like rent, eggs or gasoline. Inflation per se does not worry money and financial markets; instead, these markets track the effects of price fluctuations on nominal interest rates. High rates of inflation are expected to lead to tighter monetary policy and higher interest rates, which are considered a problem by businesses, households and governments. Long-term-bond holders, for example, would be punished harshly.

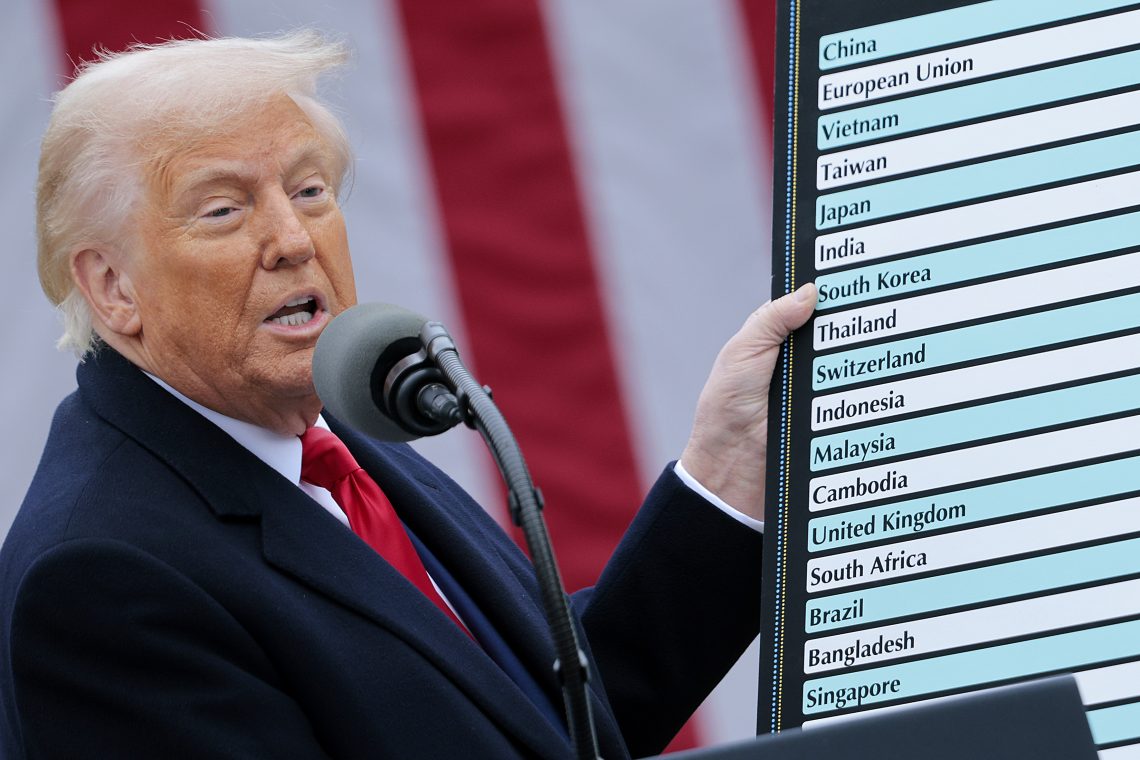

In future months, these perceptions will likely drive monetary policy, and monetary policy will affect general price levels. U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent trade measures will affect the global economy, but higher tariffs do not directly cause higher inflation. Instead, they may affect monetary policy – which in turn affects the inflation rate.

Commercial issues and price levels

Tariff protectionism disrupts trade flows. Buyers are denied the possibility of acquiring what they want at the prices at which their preferred suppliers are willing to sell. Consequently, after the introduction of tariffs, buyers may continue to purchase from their preferred suppliers but incur a tax for doing so. Alternatively, suppliers are taxed for selling to their preferred customers.

With tariffs, at least one party is subject to a tax for engaging in business transactions. Of course, buyers and suppliers can change their counterparts to avoid the tax. In that case, buyers interact with suppliers who provide inferior goods (lower quality and/or higher prices). The most competitive suppliers suffer a fall in profits, while second-rate producers benefit. Tariffs impose a tax on quality, efficiency, successful entrepreneurship and technological progress.

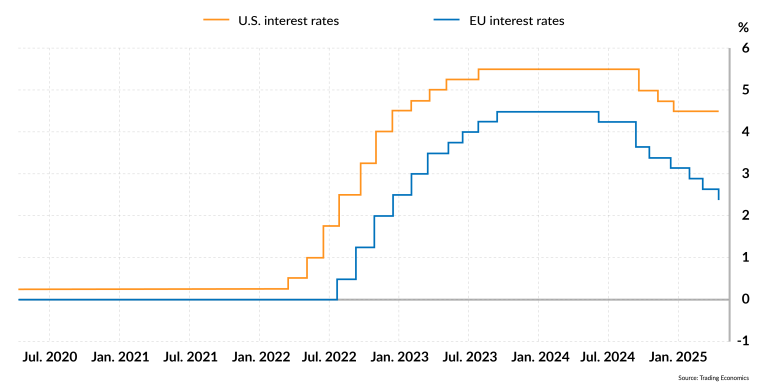

Facts & figures: U.S. and eurozone interest rates

The tariff revenues collected by governments correspond to resources that are no longer directly available to producers in the private sector. Production in the private sector drops and overall output depends on how governments spend those resources. Given the present structure and quality of government expenditure in most countries, one can reasonably suspect that a transfer of resources from the private to the public sector will not boost efficiency and economic growth.

Higher tariffs therefore violate freedom of exchange, are a tax on productive entrepreneurship and reallocate resources from private actors to the state. Note, however, that inflation is not among the immediate consequences.

But that is not the end of the story. If buyers are willing and able to spend the same amount of money as before the tariffs, then fewer goods will be purchased, or the prices of some goods drop, or people will be buying a different basket of goods. In this light, three phenomena unfold: The general price level rises because production drops and a constant amount of money chases a smaller amount of goods; some prices rise and others drop; and the general price level is no longer significant because the old basket no longer represents what people actually buy.

As a matter of fact, what really matters is the structure of relative prices.

And in terms of relative prices, there will be major changes in the months ahead. Shifts in the overall price level will be harder to assess. Prices may rise faster because of reduced output – in absolute terms or compared with the long-term trend – due to the rerouting of resources toward less efficient suppliers, efforts to redesign supply chains, and the shift of resources from the private sector to the public sector.

Greater uncertainty about the economy in general may encourage individuals to keep their assets in liquid form, which means that the demand for money may increase. If so, the excess money supply generated by weaker output can be offset or even overcompensated. Tariffs may generate either excess liquidity or liquidity shortages. Therefore, inflation can move in either direction, even if monetary policy remains neutral – whatever the term “neutral” means.

In shaping monetary policy, central bankers will take into account this uncertainty in money demand, the growing tolerance for higher inflation and the convenient option of blaming tariffs for economic problems. At the same time, they will face political pressure to increase debt-financed public spending to support export-driven industries, avoid recession, lower debt-servicing costs and fund large-scale efforts like the fight against climate change.

Scenarios

Most likely: A wait-and-see approach in Europe and easing in the U.S.

A monetary strategy that minimizes public criticism is the most likely scenario going forward, though it comes with its own hazards.

During the past few months, the money supply (M2) has increased at an annualized rate close to 1 percent in the eurozone and 1.4 percent in the U.S. Since last September, the reference interest rates have dropped from 3.65 percent to 2.40 percent in the eurozone and from 5.0 percent to 4.5 percent in the U.S.

In Europe, with the current rate of inflation there is not much room for further interest rate cuts, nor is there much need to do so. European governments find it relatively easy to finance and refinance their debt and citizens are getting used to quasi-stagnation. The European Central Bank has no urgent need to print new money to buy European treasury bills or enhance growth. For the time being, its priority is to guarantee present and future national or EU debts.

By contrast, the U.S. Federal Reserve is under pressure and could perhaps give in to President Trump and cut the reference rate to 4 percent. Big business would also be pleased with lower rates. High uncertainty could further encourage the Fed to ease its monetary policy. Instability would drive up the demand for liquidity, which would absorb at least some money printing and rein in inflationary pressures.

Lower nominal interest rates would stimulate growth in the short run and further strengthen the demand for liquidity. Monetary easing would certainly be a mistake from a long-term viewpoint, especially if the trade-policy frenzy calms down, inflation eventually picks up and Americans are no longer inclined to stay liquid. But central bankers facing political pressure in the here-and-now do not seem to be overly concerned about the long-term consequences of their actions.

Higher inflation is not around the corner and can probably be contained in Europe, but the outlook in the U.S. could rapidly deteriorate.

Less likely: Loosening monetary policy to finance excessive spending

A different scenario could materialize if central bankers on both sides of the Atlantic significantly lower interest rates and try to shun responsibility for their past mistakes and present misfortunes by laying the blame squarely on today’s tariffs. It would be a challenge to preserve economic growth while globalization crumbles and monetary policy is eased to finance grand projects in Europe and the budget deficit in the U.S.

Widespread loosening of monetary policy would be a recipe for serious trouble: The West would end up with mercantilism, massive public indebtedness, economic stagnation and increasing governmental centralization and regulation.

Least likely: Central banks stop fine tuning monetary policy

A third and unlikely scenario is one in which central bankers adopt a different strategy and become less reactive, abandoning the approach of the last 25 years – during which they manipulated interest rates, financed public debts, and provoked 43 percent and 48 percent drops in the purchasing powers of the euro and the dollar, respectively.

Central bankers could depart from this failed experiment and let economic phenomena unfold, so that prices adjust up and down and interest rates are determined by free financial markets. This would bring much-needed transparency into the economic systems, enhance policymakers’ accountability and reverse the current drive toward centralized decision-making on both sides of the Atlantic. Regrettably, these goals do not seem very appealing today, neither to political leaders nor to the public at large.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/tariffs-inflation/