The European Central Bank’s monetary policy is under pressure

Europe’s economy has recovered from the dislocations and restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic, but the overall picture remains disappointing. During the past decade, the average annual growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) in the European Union was about 1.5 percent, and preliminary estimates for 2023 are below 1 percent. Some believe that the outlook for 2024 is better (+1.4 percent), but that would hardly be satisfactory.

Facts & figures

Fragile public finance conditions burden many European economies, while high taxation and pervasive regulation stifle entrepreneurial spirits. The quality of education is low, and demography puts a lid on the resources available for investments (senior citizens tend to save less than working-age individuals).

However, European policymakers do not appear overly concerned. Instead, they celebrate their success in taming inflation and, seemingly, avoiding a recession.

Facts & figures

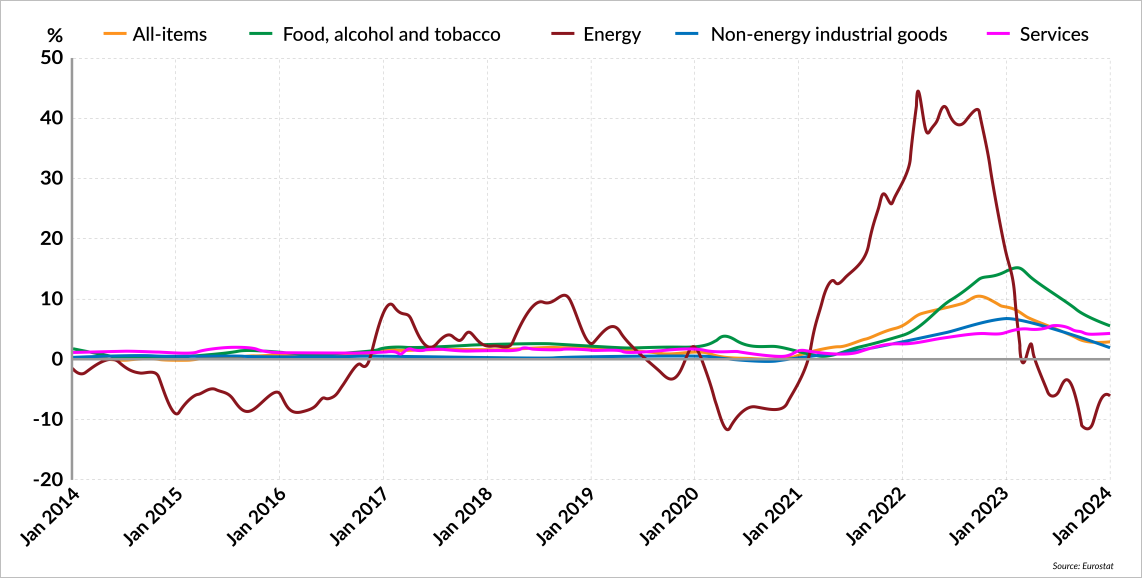

Inflation in the eurozone

Governments are planning to direct very significant amounts of taxpayer money toward grand long-term projects, such as the green energy transition and the electrification of transport. They are persuaded that forthcoming technological advances will open new opportunities for exciting regulatory activities.

Brussels’ economic policy wound up relying on the only instrument it trusted: monetary policy.

Yet the EU authorities do not offer prescriptions for enhancing economic growth. Technocrats in power seem to believe that most troubles are local and do not require structural changes, let alone free-market solutions. In practice, Brussels and the major member states are happy to post positive growth figures, no matter how small, and to keep refinancing their outsized public debts (taking out new loans to pay off existing arrears).

Monetary policy highwire act

This approach is understandable. Over the years, European policymakers have transformed the highly successful free-trade zone across Western Europe into a regulatory maze dominating most of the old continent. As a result, Brussels’ economic policy wound up relying on the only instrument it trusted: monetary policy. However, monetary and credit policies are difficult to apply well. If, on the one hand, the policy is too strict, high interest rates may choke investments and put heavily indebted households into serious trouble. For example, this phenomenon already characterizes the United Kingdom, and Brussels has taken note.

On the other hand, if monetary policy is too generous, it triggers inflation, which stifles investments, financially harms broad groups of the population (especially wage earners) and blasts public finances – as is happening in Europe today to the likes of Italy and France.

In principle, the best monetary policy is no monetary policy. Although markets are imperfect, tweaking the price signals – interest rates are prices of money – leads to distorted decisions with long-lasting consequences. This explains why monetary authorities should rather sit tight and limit their activities to checking whether financial institutions cook their books, and letting the market know if they do.

However, central bankers are usually appointed in the hopes that they do something – helping the politicians pursue goals that they are unable to attain otherwise and looking the other way when necessary. Over more than a decade, central bankers performed as expected. Indeed, until mid-2021, these officials thought they had it all: they engaged in money printing, manipulated interest rates downward and increased financial market regulation.

In other words, they neutralized the consequences of the potentially explosive mix of high public indebtedness and low economic growth by buying treasuries with the newly printed money. At the same time, they offset the pressure on prices by sterilizing the extra money put into circulation by reducing the so-called money and credit multipliers, the mechanism through which the newly printed money is transformed into easy credit for the private sector.

However, the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank (ECB) now knows that it has run out of luck. Pumping more money into the system could be dangerous, possibly even killing the euro – especially if the market fears or anticipates future inflation.

The ECB’s shift in monetary policy communication

This explains why the ECB has become uncharacteristically cautious. Now, it insists that the war against inflation is not finished. Its leaders hardly miss an opportunity to declare that monetary policy will remain rigorous and that expectations of an imminent drop in interest rates are premature.

There is still much excess money in circulation, and it will not be absorbed by the system soon.

Many highly indebted companies across the EU are not pleased. Yet, the discontent is limited and leaves open the question of whether current monetary conditions in the EU (and the euro area in particular) are indeed tight. According to the data, bank lending to households and companies in the eurozone is almost stagnant in nominal terms (0.5 percent growth on a yearly basis) but is falling if one considers inflation. Moreover, real interest rates in the euro area have almost reached their average historical level of 3 percent.

Monetary conditions are neutral by these broad measures. This matches consumer behavior. Although households and companies are confident that interest rates will not rise further, they remain cautious. Many are already overexposed and do not believe that the future justifies taking much risk.

In fact, there is still much excess money in circulation, and it will not be absorbed by the system soon. For example, at the end of 2023, the eurozone M2 money supply (the sum of currency in circulation and overnight deposits, plus longer-term deposits) reached about 15 trillion euros, up from about 8 trillion in 2008 and 10 trillion in 2015. This liquidity means that any inflationary spikes would find plenty of fuel.

Current monetary conditions are consistent with “normal times” (the historical averages). However, there is still much liquidity sloshing around, and the financial balance sheets of governments, households, financial and non-financial companies are fragile. It would not take much to rock the boat. This could occur if, for example, the economic climate suddenly changed and monetary authorities felt obliged to intervene with countercyclical actions. These possibilities correlate with three different scenarios, which are presented here in decreasing order of probability.

A soft recession in Europe is even more likely if geopolitical tensions increase, supply bottlenecks constrict, protectionist threats from the United States become true and the Chinese economy further slows down.

Scenarios

More likely: A soft recession before the end of 2024

The first scenario runs contrary to the optimistic predictions of, for example, the International Monetary Fund. The poor structural situation of selected key economies justifies this hypothesis. Germany is particularly vulnerable to protectionism and to the waves of old and new Asian high-tech competitors (including China, India and Vietnam). France is experiencing ongoing labor-shortage difficulties (relatively early retirements and unfilled vacancies) that are hurting its manufacturing industry. The Italian economy has been stagnating for the past 20 years, and no structural reforms are in sight.

A soft recession in Europe is even more likely if geopolitical tensions increase, supply bottlenecks constrict, protectionist threats from the United States materialize and the Chinese economy further decelerates. Will the ECB stay put, freeze the money supply and possibly let real interest rise further? This author supposes that it will not, especially if inflation approaches the 2 percent benchmark. Under overwhelming political pressure, a new season of monetary manipulation would be launched. For a while, stock markets and treasury ministers would breathe a sigh of relief, but the fundamental problems saddling European economies would not go away.

Less likely: Gradual improvement

Under the second scenario, government and ECB business-as-usual policies continue, the old continent stagnates or grows at a snail’s pace (less than 1 percent a year), inflation slowly declines, and the public finance situation stabilizes or improves slightly. That would probably be the preferred set of conditions for European central bankers, who would resort to the old recipe: cut the lending rate by about half a percentage point by the end of this year, and keep the credit market in check by fine-tuning regulation (through explicit rules and moral suasion).

The least likely: A burst of growth

A third scenario features scores of good news: international tensions and trade barriers abide, and, in the aftermath of the 2024 elections in Europe, Brussels engages in deregulation and less intrusive central intervention while having second thoughts about how to go about the energy transition and global warming mitigation. Economic growth accelerates by leaps and bounds, and monetary policy is no longer a priority: interest rates remain stable at the current levels, and nobody really cares if credit expands. Local and central authorities are too busy taking credit for the strong performance of the economy to be bothered by monetary policy nuances.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/inflation-recession-growth-monetary/