PISA results: Poor education is no recipe for economic brilliance

In December 2023, PISA published the latest edition of its international report on student test scores for the year 2022. The results do not augur well for the future of Western countries as robust, modern economies and innovative societies.

PISA stands for “Programme for International Student Assessment.” The system currently covers all 38 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, plus 43 other countries worldwide. The tests measure the cognitive skills of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science and reading.

The top five scholastic performers were Singapore, Macao, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, outclassing their peers in Europe and the United States in all three areas. Singapore students led the global tables in the mathematics assessment with 575 points. They also excelled in reading (543 points) and in science (561 points).

The OECD average score in mathematics was 472 points, in reading 476 points and in science 485 points.

Some European and OECD countries like Estonia, Switzerland, Canada, Ireland or the United Kingdom had some higher-tier individual results, depending on the measure. Japan and South Korea, both high-performing Asian nations, are in the OECD while China’s participation in PISA has been limited to some geographic areas only. Nevertheless, trend analysis of PISA results reveals a decades-long decline that began well before the Covid-19 pandemic. Students in Europe and the U.S. performed poorly in 2022, and, importantly, significantly worse than in the past, especially in mathematics and reading. If confirmed, this trend will have far-reaching social, economic and, in the end, political consequences.

Facts & figures

The main question arising from the PISA scores regards the quality and characteristics of today’s educational systems, especially in the Western world. Until the late 1960s, it was generally believed that education should equip young people with adequate knowledge in the fields of language and literature, history, geography, mathematics and science.

What went wrong

In the past, selective grading that allowed teachers to assess scholastic performance of each student and identify the outstanding, good, average and poor performers served various significant purposes. It encouraged students to intensify their efforts, rewarded good performance and provided signals to their families and prospective employers. The emphasis was on cognitive skills (that is, the acquisition of systematic information), quantitative skills, problem-solving abilities and abstract and logical reasoning. These days, such grading systems are considered discriminatory, humiliating and stress-inducing.

The accepted response to problems stemming from failures at school has been welfare-state support and income redistribution.

It was also understood that the education process would develop non-cognitive skills: the ability to concentrate, hard work habits, a sense of individual responsibility, discipline and the ability to accept (and react to) setbacks. The families of students and those in charge of educational programs shared this general framework.

The picture has changed since a new generation of politicians, teachers and parents shaped by the social developments from the late 1960s to the 1980s began to alter the rules of the educational game in the 1990s. The bond between parents and teachers weakened, often becoming a source of tension. The accepted response to problems stemming from failures at school has been welfare-state support and income redistribution. Socializing has become an accepted substitute for hard work on core competencies.

The performance of schools and teachers was measured according to passing rates rather than the quality of instruction and employment opportunities available to competent students. Finally, careers in the civil service have been making cognitive skills less critical than networking and political loyalty. Efforts to adjust to the expectations and demands of immigrants (and of their children) may have also played a role.

As a consequence, in countries where the shifts listed above were pronounced, the quality of education deteriorated. Fast technological advancements also played a role. On the one hand, technology increases labor productivity, while expanded learning opportunities compensated for deficient skills. On the other hand, however, students use their smartphones and laptops for non-educational purposes while attending classes and are easily distracted by these devices from doing schoolwork. The immersive world of high-tech gadgets appears to hinder the young generation’s ability to concentrate, memorize, take notes, elaborate fragmented knowledge and develop autonomously informed critical thinking and linguistic skills.

To be sure, some Western nations recognize the in-class distractions and associated long-term risks, and are taking steps to address the issue. At the start of this year, for example, the Dutch government began phasing in a ban on mobile phones, tablets and smartwatches from classrooms in the Netherlands.

Tertiary education also lags

The PISA results leave no doubt about the drop in educational quality within the context of secondary education, the exception being Asian countries with deeply ingrained traditions of rigorous studying for imperial examinations and some less-affluent countries where improving living standards have created new opportunities and encouraged schooling.

Grading becomes increasingly generous as the schools seek to attract new students and avoid falling behind in the rankings.

Tertiary education is also in mediocre shape. Of course, having a college degree still helps: wages are higher for those with one than those without, and career prospects are brighter. Also, unemployment rates are lower among those with a bachelor’s degree or above. Presumably, this is due to the difference in quality between those with and those without a bachelor’s degree. However, the fact that higher education still confers advantages does not rule out the alarming possibility that marketable skills in the two groups are dropping concurrently.

Looking at anecdotal evidence, as the quality of secondary education worsens and colleges accept lower-performing students, curricula usually soften. Grading becomes increasingly generous as the schools seek to attract new students and avoid falling behind in the rankings. As a result, young people stay longer at school and college, their cognitive and non-cognitive skills decline and the signals (grades) that the educational system sends to potential employers become increasingly useless.

Wrong diagnosis, terrible cure

These phenomena have consequences, especially in the West, where the decline in educational quality is more pronounced. This report emphasizes resulting social tensions, pressure for more redistribution and the crises of pension systems.

In statistics, when values change at an aggregate level, the distribution of their components often becomes more dispersed. For example, fast growth of gross domestic product (GDP) may lead to a broadening of the difference between the top and the bottom income earners. That does not necessarily mean that the poor become poorer. Often, the top performers are simply rewarded more than those who trail behind.

Regardless of their causes, increases in inequality lead to louder calls for income and wealth redistribution. Policymakers are often happy to oblige.

Similarly, the overall drop in educational standards does not preclude some top students leaving school highly qualified, perhaps because they had come across excellent instructors or their family environment helped them develop their cognitive and non-cognitive skills. When this happens, the gap between the top and the bottom performers widens, as does income inequality.

Income inequality can be, in fact, problematic in contexts dominated by the rhetoric of “social fairness,” and the notion of social justice requires that the haves compensate the have-nots. Regardless of their causes, increases in inequality lead to louder calls for income and wealth redistribution. Policymakers are often happy to oblige. They ride the wave to obtain electoral success.

Not surprisingly, more redistribution tends to lead to more government expenditure and higher tax pressure. In other words, poorer education leads to more redistribution, more taxation, lower net-of-tax incomes and weaker incentives to acquire and require satisfactory educational standards. This vicious circle is difficult to break, let alone reverse.

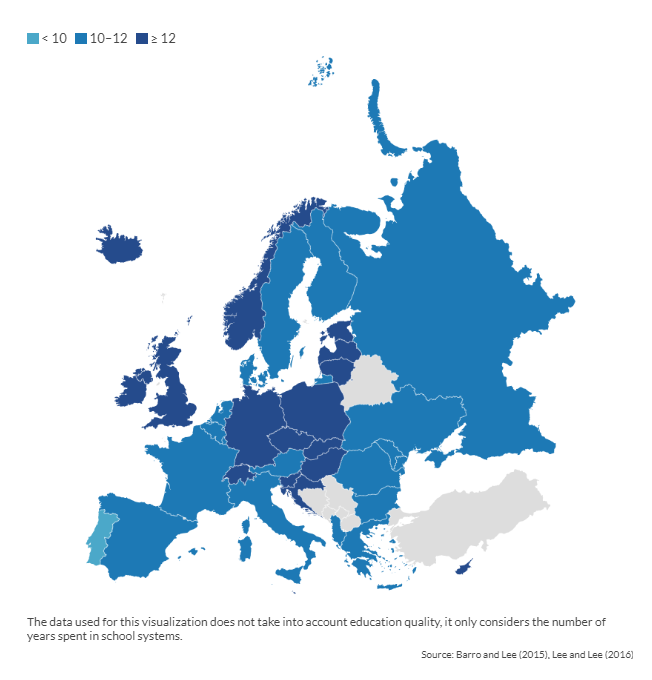

The outlook for pensions also is deteriorating. During the past 30 years, the average length of schooling has increased significantly. For example, in Germany and France, it was 9.0 and 8.3 years in 1990, respectively. It reached 13.1 and 11.9 years in 2020. Now, if average skills remain the same (or deteriorate) and the length of schooling is extended, what are the consequences of entering the labor force later? Either pensions become smaller, social security contributions must grow or the retirement age is delayed.

Facts & figures

All these phenomena already seem ubiquitous. They add to current demographic trends, which will be hard to change. Fast technological development could be the much-needed magic wand to make relatively poor human capital productive. However, as of now, economic policies in most Western countries stem from priorities that often stifle private investments and entrepreneurship, especially in Europe. Technological progress can still be vibrant, but it does not generate much growth in productivity in these circumstances.

The mechanism described above will unfold its full consequences over years, not months. The fact that this situation does not draw much immediate attention makes it even scarier.

There are only two ways Western educational systems can reverse the current trend and offer more appealing prospects.

Scenarios

Can the West buck the trend and offer different perspectives? The OECD has proposed 10 remedies, including such generalities as “ensure high-quality education staff,” “limit the distractions caused by using digital devices in class” and “build strong foundations for learning and well-being for students.” None of the recommendations addresses the origins of the crisis of state-run educational systems.

There are only two ways Western educational systems can reverse the current trend and offer more appealing prospects.

Allowing private schooling to flourish

This would open the way for educational entrepreneurs and managers to enrich their diverse proposals and allow parents to choose their preferred sets of teachers and curricula. And, naturally, to assume personal responsibility for their choices.

Bringing about radical reforms in state schooling

This would require a fundamental update of the very notion of education and how the bureaucracies assess the quality of schooling.

Most likely: No change, steady decline

Regrettably, neither of these solutions is in sight. Instead, the vicious spiral that links poor education to inequality, social tensions, more government intervention and, finally, low productivity and stuttering economic growth will likely dominate the future of many Western countries for years to come.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/worsening-2022-pisa-tests-results-oecd/