A comment on PISA and W. von Humboldt’s education ideal

True education is not about filling the mind with knowledge, but about training it to think.

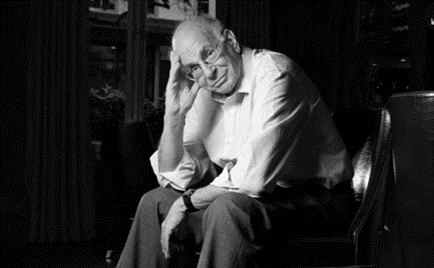

Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835)

TAKE AWAY

Though participating 15 year old students must be able to apply their accumulated knowledge to solve problems, the kind of input/output methods used in the PISA Study always have been controversial. The recently published Study again has received a great deal of attention during the past months. Not only the bad reports about rapidly dropping performance levels in public schools on most counts, but especially within the exact sciences was a shock in several EU countries. Also the appalling illiteracy in multiple subjects and an increasing disposition to use violence among young people has alarmed the public at large.

The critical allegation that today’s school systems are turning out illiterates, failures and sometimes even morons more readily than any talented, well-educated individuals was hard to miss. Have the minds of the rising generation already been polluted by the ‘politically correct’ general language of classroom instruction and utterly confused by the ideologies of ‘Woke’ or ‘Cancel Culture’ to be able to learn how to think? Or are the present national curricula indeed liable to the trendy reinstatement of Marxist doctrines that well over a century ago were firmly driven back into the circles of cranks and demagogs?

However, a real and lasting education comprises more than just the acquisition of knowledge – individuality and personality as well as the development of talents play an equally decisive role. Therefore, Wilhelm von Humboldt defined individual education as ‘the continuous interaction of the theoretical understanding and the practical will’.

Program for International Student Assessment

In spring of 2022 worldwide well over 600,000 15-year-old students from 81 countries took part in the famous PISA Study (Program for International Student Assessment). The PISA tests are designed to show the general reading skills as well as logical thinking and problem-solving skills in mathematical tasks and the basic knowledge in the natural sciences taught. Some information about each student’s background, self-image or learning strategy is also collected. Regardless of the grade level attended, all participating 15-year-old students are checked. This fact strongly influences the significance of the PISA results, as for example in Sweden students who barely spoke Swedish at the time were not invited to take part in the tests.

These huge data sets are then collected, analyzed, evaluated and adjusted by school experts and statisticians who assume that they are thereby measuring the amount of knowledge students have absorbed and reproduced in a given time. At any rate, results are then assembled and meticulously compared (school performance comparisons) with the respective output of such nations, which are hardly equal in their economic or socio-political structure like China (PRC), Denmark, Uzbekistan, Germany, Singapore, Liechtenstein or Finland, among countless others. In other words, as with all empirical educational research, not only the meaningfulness of the PISA Study with its focus on the selective output of basic skills and employability, i.e. the ability to survive in the labor market, is limited. The results also generate too little practical suggestions that schools or the respective administrations could use for their work.

Following the publication of the study in the participating countries, the findings are typically met either by jubilance, indignation or by a somewhat spoiled national pride in the respective state-run education administrations. Alarming headlines in various newspapers and the social media predictably cause a nationwide outrage and lead to politically motivated finger pointing, special parliamentary sessions and for a short time to superficial public debates. Sadly and ominously in most of these discussions, not only the venerable concept of ‘Bildung’ is conveniently ignored. The intensifying philosophical disorientation of today’s students paired with the lack of an ethical frame are also shrewdly kept out of the debate as much as possible. As the PISA study does not provide an indication of the actual general knowledge of the students it seems the emphasis is on the in- or decrease of economically usable human capital and on its importance for the economic growth and performance of the participating countries. Thus the PISA-Study’s pragmatic understanding of modern education fittingly discounts the vital tradition of a well-rounded education matching the development of a unique personality, a lifelong learning approach and the avoidance of a limiting specialization. However only a comprehensive educational attitude can foster a student’s talents, develop the ability to be curious to explore and to be perceptive of and engaging with her or his own fellow citizens and the society at large.

Have the minds of the rising generation already been polluted by the ‘politically correct’ general language of classroom instruction? Are the utterly confused and narrow-minded ideologies of ‘Woke’ or ‘Cancel Culture’ already brainwashing an entire age group? Or are the present national curricula indeed liable to the trendy reinstatement of Marxist doctrines that well over a century ago were firmly driven back into the circles of cranks and demagogs? It might be useful therefore to recall and briefly summarize the main points of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s classic Bildungs-Ideal.

Von Humboldt had never attended school himself

Prussia’s crushing defeat at the hands of Napoleon I in the twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt in October 1806 and the resultant humiliating occupation prompted King Friedrich Wilhelm III to initiate a general program of radical military and societal reform in Prussia. Gerhard von Scharnhorst (1755-1813) was appointed to head the military reform commission and Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein (1757-1831), acting on exceptional powers granted by the King had been entrusted with carrying forward a vigorous societal restructuring and recovery program. Stein’s reform program embraced decisive steps toward a thorough reorganization of the Prussian government, the emancipation of the peasants, the creation of local self-government and a total overhaul of Prussia’s education system. For the latter task vom Stein had chosen Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) to undertake this enormous task, not because of his specific training, rather due to the quality of his mind. W. von Humboldt, who had never attended school himself and had abandoned his studies after just four semesters, with some reluctance accepted his appointment as Director of Public Worship and Education, an influential section in the Prussian Ministry of the Interior. Although he only lasted some 15 months in the department, this short period of time was enough for him to draft several comprehensive memoranda (school plans) which, taken together, are classic pronouncements of the application of his Bildungs-Ideal to education and thus are the substance of Humboldt’s education program. In far less than one and a half years he shaped the structure of a modern university, founded the Universität zu Berlin (later Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität) and made the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814) its first rector.

Mindless memorization

By following today’s teaching methods of hammering home facts, rules and numbers, education looks almost to be only possessed by those who can cleverly reproduce this stored knowledge at the right time and place. Most centralized school systems are similar to vocational or professional training and may even be viewed as a sort of a utilitarian enterprise that prepares students collectively for particular ways of earning a living later on. Wilhelm von Humboldt described this traditional teaching and learning method as a ‘mindless memorization’ and mocked it even as among the most useless tools to handle one’s life. In his ‘Bildungs Ideal’ he distinguished these methods sharply and markedly from a comprehensive education based on a lifelong learning process with a connection of a student’s self with the real world.

The timeless significance of Humboldt’s ideal thus can be found in his definition of education. For him a real and lasting education comprises more than just the acquisition of knowledge – the development of individuality and personality as well as of talents play an equally decisive role. Schooling for him does not mean transporting any material, rather it is a connection of a student’s self with the outside world. Thus he defined individual education as ‘the continuous interaction of the theoretical understanding and the practical will’. Learning should strive for making both more similar to each other. This process of individualization through which young people can develop their own personality requires a sensitivity to the objects that characterize their physical and social environment. Because only the outside world conceivably embraces diversity, the student individually must produce education in a subjective manner, and thus needs the connection to the surroundings. Instead of simply imparting knowledge, Humboldt placed the well-rounded education of children. In other words, he refers to education as the acquisition of a system of morally desirable attitudes through the transmission and attainment of knowledge. This is done in such a way that people can choose, evaluate and define their position within the reference system of their own history and standing in their social world. Thus, they acquire a personality profile and gain orientation in life and action. Only through a process of individualization, people can develop their own personality.

According to Humboldt’s perception of schooling, the teaching subjects must be ideal in their structure and challenge the basic intellectual abilities of the young human being. The objects of education are readily found in traditional culture and are mostly based on the great, unique creations and discoveries of humanity, which thinking people incorporate in an active, critical process. The topics must not indoctrinate the mind, rather they should stimulate the imagination of young people and deepen their views and feelings.

Children are born with a wealth of talents and abilities that needed to be awakened and developed. Since most skills often only reveal themselves at a later time, a foundation had to be created on which all special talents, be they artistic, scientific or manual, could be further developed. Although Humboldt understood well that a child would later have to earn a living, for him these necessities were not the purpose of the school, quite the opposite. Schooling for him was the formative space through which kids passed before being exposed to the immediate needs of their respective daily life. In the classroom the future craftsman, the aspiring scientist or a would-be teacher should get to know a free spiritual world of wonders. And even kids from the humblest background should be allowed to stay in school for a while before life puts ‘its shackles on them’, as Humboldt phrased it. Accordingly, young people may not unnecessarily be burdened with the real worries and social constraints of everyday life at school, instead they should learn to discover these worries and constraints, the should immerse themselves into the phenomena of their surroundings and mature without too many early concerns. In other words, Humboldt suggested that they should be granted time to develop a beautiful or not so impressive character, grow to a full human being or at least to a decent person, and should not be molded from early on to be only a highly specialized professional or worse, a submissive, obedient or dreary fellow citizen. Only life and parents would do all this, and the school had no preemption. Thus education ought to unleash and exercise all human powers, both mental and emotional. In Humboldt’s view thinking and learning are not only objective processes as has been claimed since the Enlightenment – they are also individual and highly emotional activities. As both take place in the head of a single person and never are collective, both individual mind and spirit must be trained, educated and encouraged.

Development of individual thinking

To summarize, for Wilhelm von Humboldt the inclination towards higher things, towards ideality, is innate in human beings. He wanted to attain the uniqueness, the specialness that characterizes normal people and he sets the individual strictly apart from the collective. The education of the whole person and the development of individual thinking he placed at the center of his Bildungs-Ideal. By acquainting young people with the world of ideas and wonders, with vanished cultures and by learning about seminal invention or making them curious to understand great discoveries, most adolescents learn to perceive their own mind and experiences and thus gain essential insights for life. In this way they become aware of themself, develop individuality and grow to be a personality.

Individuality lies in the specialness and the urge for ideality in the innate striving for self-perfection. Humboldt considered the basic powers of a human being to be reason, feeling, imagination and perception.