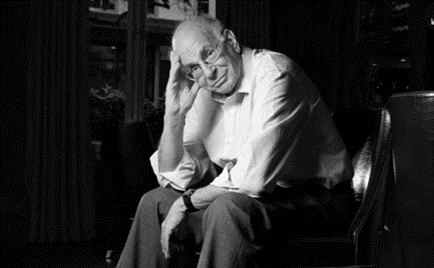

James McGill Buchanan (1919-2013). A Short Appreciation 10 Years after his Death.

It is 2023, and lest we forget one of the most seminal minds of our times, we should briefly recall the important life and work of James McGill Buchanan who died 10 years ago on January 9, 2013. Buchanan belonged to that long past generation of American social scientists whose extensive work arose from the comprehensive view of interdependent academic disciplines.

The governor’s grandson and WWII officer

It was not hard to tell from the charming melody and the tone of his language, that Jim Buchanan was a ‘Southerner’. Born near Nashville in the US state of Tennessee, he grew up there on a ranch that had been in the family for several generations. His grandfather, John P. Buchanan, served as governor of Tennessee during the late 1890’s. In his autobiography Better than Plowing and Other Personal Essays (1992), Buchanan offers some wonderful insights into his winning personality, his growing up in rural Tennessee during the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s and the development of his ideas. In WWII he served as an officer in the US Navy under Admiral Nimitz in the Pacific war theater and was decommissioned in 1946.

Buchanan began to study economics and wrote his master’s thesis at the University of Tennessee. However, he continued his studies at the University of Chicago where he met not only Milton Friedman (1912-2006) but also his teacher and Ph.D. supervisor Frank Knight (1885-1972). The later succeeded after only a few weeks into his courses to rid Buchanan of his socialist ideas and his naive thinking of a distributive welfare state. But not only Frank Knight’s direct scientific influence made Buchanan one of the leading liberal (European sense) thinkers of our time. Buchanan was also strongly influenced by the works of great Italian financial theorists such as Lottini, Davanzatti or Galiani.

Only unanimous taxes and government spending can be justified.

In particular, however the works of the Swede Knut Wicksell (1851-1926) determined Buchanan’s early thinking, especially Wicksell’s taxation doctrine, which states that only unanimous taxes and government spending can be justified. This stands in sharp contrast to today’s welfare state, in which taxes are used almost exclusively as an instrument of redistribution and as a charitable, solidarity contribution. For Buchanan taxes are exclusively prices for the provision of public goods, because there is no connection between an individual tax liability and the individually received state benefits. However, since politicians usually want to be re-elected and because they try to make themselves popular and sometimes indispensable with tax gifts and all kinds of promises (at the expense of the general public), they reject simple tax systems that have the same effect on everyone. Even if this insight can already be found in Machiavelli’s The Prince, in B. Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, or in Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, Buchanan managed to prove here that this political self-interest in representative democracies usually leads to grave state and socio-political problems. The individual citizen has to make these contributions to finance those tasks that the state then makes available to everyone in the supposed interest of a collective well-being that has hardly ever been defined. He distinguishes here essentially between two eminently important democratic levels: While the rules of a constitution are discussed, negotiated and passed on the first level, the second is about preserving individual freedom by complying with and enforcing these rules.

An author of seminal books

Increasingly, Buchanan began to focus on a hitherto largely neglected part of economics by developing the new subfield Constitutional Economics. Together with his friend and colleague Gordon Tullock (1922-2014), Buchanan published The Calculus of Consent. The Logical Foundation of Constitutional Democracy in 1962. In this seminal book Buchanan and Tullock break with past theories of political science in their analysis of democratic decision-making processes. They approached the basic problems of politics, using the technical tools developed in modern economics and game theory. This book was a breakthrough and soon became a classic within the field of political economics. By discussing political institutions similar to the way economists discuss the market they established Theory of Public Choice. They begin with the individual as he participates in the processes through which group choices are organized. Government is treated as a co-operative endeavor on the part of any number of people of differing tastes to increase their abilities to reach their separate individual objectives. As in economics, the basic question becomes one of efficiency—which set of governmental institutions will best serve the individual ends of the citizens. This work represents a major step towards formulating a scientific theory of democracy.

In his almost equally famous book The Limits of Liberty. Between Anarchy and Leviathan (1975) Buchanan shows how these political processes undermine the understanding of democracy and how the current welfare states degenerate more and more into haggling democracies (Schacher-Demokratie, F.A. von Hayek). Asked for a short description of the Public Choice approach, Buchanan once famously replied with the well-known reference to the fox, which should not be left to guard the chicken coop.

In his multiple works on the methodology of economics, such as What Should Economists Do? (1979) or in his much-neglected book Cost and Choice (1999), Buchanan criticized the widespread approach that categorizes economics as a science of choice or the allocation of scarce resources. Firmly based on the foundation of Austrian Economics, he argued convincingly that economics is a theory of the realizations of goals, and not a goal-choice theory. Individual assessments and targets are therefore always subjective and lie beyond scientific knowledge. In the 1990s, Buchanan successfully introduced the concept of ‘generalized increasing returns’ into the free trade debate. For Buchanan, increasing international networking is leading to an ever-widening division of labor and thus to ever greater productivity with higher growth. This insight not only influenced the globalization debate, but just as profoundly the discussion about work ethics or the legal limitations on working hours.

1986 Nobel Prize in Economics

Long overdue, James Buchanan was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Economics for developing the Contract Theory and Constitutional Foundations of economic and political decision-making. The beautiful complete edition of his work, which the private Liberty Fund (Indianapolis) began to publish several years before his death, contains not only his 30 books but also some 300 essays and other sundries on economics and social theory. Buchanan’s extensive work arose from his deep knowledge and comprehensive humanistic understanding, which unfortunately proves increasingly rare among US social scientists. The inner coherence and systematic development of his oeuvre, his honest scientific approach and his seminal academic influence, but not least his restrained humor, so typical of a ‘Southerner’, are legion.