The actuality of Gottfried von Haberler’s

Theory of International Trade in the era of Trump

Gottfried von Haberler’s contributions to international trade theory and policy have been disruptive and yet the works written by one of most prominent Austrian economists are unfairly undervalued when analysing modern events in world economy, such as the “new protectionism”. Gottfried von Haberler’s theory remains a cornerstone of modern international trade. His simple and useful idea is basically moving analysis away from labor costs to opportunity costs (e.g. the loss of other alternatives when one alternative is chosen). The actuality of Haberler’s analysis is due to the integration into standard economic curricula and its role in moving trade theory toward more realistic, multi-factor models.

Core actuality of the theory

From a theoretical perspective, Haberler replaced the famous David Ricardo’s too restrictive “labor-only model” with the principle of “opportunity cost”, defining the cost of a good by what must be given up producing it. This change allows the international trade theory to include multiple factors of production like land, capital, and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, he introduced the Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) (even if originally, he called it the ‘production substitution curve’), which is now the standard graphical tool for illustrating trade-offs and comparative advantage in economics.

Finally, unlike earlier models that assumed constant costs, Haberler’s framework explains trade under increasing, constant, and decreasing returns to scale. This makes the analysis applicable to diverse real-world scenarios, such as partial specialization where countries produce some of a good instead of entirely abandoning it.

Modern applications and context

Haberler’s studies remains essential for evaluating trade policy, especially his early advocacy for free trade as an engine for growth in developing countries. His theory helps explain modern trade dynamics, such as why an economy like India may shift specialization based on evolving comparative advantages in services or manufacturing rather than just labour-intensive goods. While “New Trade Theory” (focusing on economies of scale and firm heterogeneity) has added more nuance, Haberler’s opportunity cost still represents the base upon which these modern refinements are built.

Despite its relevance, Haberler’s theory relies on certain ideal conditions that are often at odds with today’s economy:

- Perfect Competition: the theory assumes markets are perfectly competitive, which is rarely the case in sectors dominated by large monopolies and MNCs.

- Full Employment: the theory operates on the assumption that an economy is at full employment, while trade is often affected by involuntary unemployment.

- Factor Mobility: the theory assumes factors (like labor) are perfectly mobile within a country but completely immobile between countries, a distinction blurred by modern migration and global capital flows.

Despite its limitations, Haberler’s theory remains theoretically valid also, and perhaps especially, in the ‘Trump era,’ though it is being actively challenged by current protectionist policies. While Haberler’s logic describes the economic costs of trade, modern policy often prioritizes national

security and sovereignty over the pure efficiency his theory advocates.

Why his theory still holds in the real world, despite many forces tend to retreat the economy towards protectionism? First, because opportunity cost still persists: Haberler’s core contribution—that the ‘cost’ of a product is what you give up making it—remains an inescapable reality. Even today. For example, when Trump’s administration imposes tariffs pretending to protect domestic manufacturing, Haberler’s theory shows that production factors (e.g. labor, capital) are diverted from more efficient sectors to less efficient ones, incurring a ‘cost’ in lost productivity. Secondly, also the ‘tariff pass-through’ effect does persist. Recent studies on Trump’s tariffs confirm Haberler’s warnings about the burdens of protectionism. These tariffs often lead to ‘full pass-through,’ where the costs are borne entirely by domestic (U.S.) importers and consumers rather than the exporting country. Exactly the outcome Trump’s agenda would not achieve! Finally, even critics of free trade use Haberler’s PPF to model the trade-offs of their policies, meaning that they undoubtedly believe it.

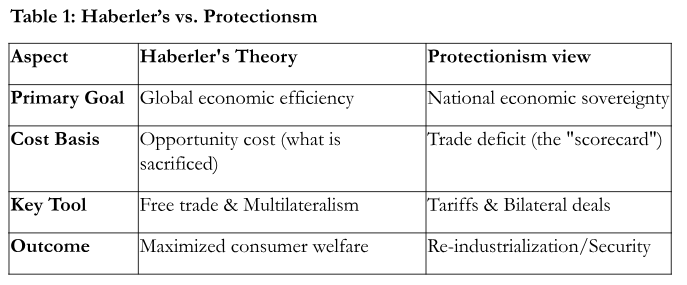

Roughly speaking, Haberler’s theory represents a challenge for new protectionism. First, because of the ‘security vs. efficiency’ trade-off: modern U.S. trade policy increasingly views trade through a security lens rather than a purely economic one. Haberler’s theory assumes a goal of maximizing global welfare through efficiency, whereas nationalist policies like Trump’s ‘American First’ policies prioritize national power and the reduction of trade deficits as a scorecard for political success. Secondly, the danger to depart from multilateralism: Haberler’s thought supported the post-WWII liberal order based on shared rules. Instead, current nationalist policies favor bilateralism and transactional deals, which Haberler

generally viewed as less efficient than broad, rule-based free trade. Finally, one of Haberler’s key assumptions is the existence of a ‘full employment’. Modern protectionism is often rooted in the belief that free trade or globalization has caused persistent underemployment in specific industrial regions (e.g. the ‘China Shock’), leading policymakers to contrast Haberler’s efficiency arguments in favor of supposed job-retention goals.

To conclude, Haberler’s theory is more than ever a valid diagnostic tool to explain why tariffs will raise prices and distort resource allocation in a non-free trade world. Although it is being rejected as a policy guide by authoritarian leaders who value other strategic outcomes more than pure economic efficiency and welfare, the pureness and avantgarde vision by Haberler is still there to guide enlightened policy-makers who believe that through free trade and liberal order a better world could be achieved.

Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers *

(* Opinions expressed are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer)