The New Washington Consensus: What does it entail?

In late April 2023, United States National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan disclosed the new global economic guidelines that the current administration would pursue during its remaining months and, if secured, the next term.

In contrast with the past, the guidelines’ creators believe that free market-recipes are no longer good enough to respond to the challenges that the U.S. needs to meet. The newest ones are climate change and its consequences, the increasingly vulnerable supply chains and the ongoing weakening of the domestic industrial structure. Therefore, it is argued that updated vision and responses are necessary.

New priorities for the West

Looking closer, it turns out that Mr. Sullivan and U.S. President Joe Biden advocate a radical shift in the country’s trade and industrial policies, in effect a “New Washington Consensus” (NWC). The word “Washington” in the name underscores that the project has been designed and carried out by the U.S. government, while “consensus” conveys the idea that friendly countries may join in and cooperate with American policymakers. The NWC has little in common with the recommendations that Western academic circles and international organizations put together in the late 1980s to help spur growth, especially in developing countries. Known as the Washington Consensus, the recipe emphasized free trade, deregulation, tolerable taxation and moderate public expenditure.

The argument favoring government intervention in selected industries is not new. In the past, it was known as the “strategic industry” argument and led to widespread legislation giving a leg up to selected companies, projects and industries.

So, what does the new approach advocate? The guidelines do not say much about what should be done about climate change and energy transition but confirm that the government will set the agendas in these areas and that taxpayers will be asked to finance public expenditure to face the challenge.

The updated manifesto clarifies that free trade, free-market prices and deregulation are no longer priorities. Instead, international trade and market-driven specialization will become the object of scrutiny to ensure that national security is not in jeopardy. The U.S. administration explicitly names China and Russia as threats and selects physical and digital infrastructure, semiconductors and critical minerals as the main objects of the NWC approach.

Failed ideas

The argument favoring government intervention in selected industries is not new. In the past, it was known as the “strategic industry” argument and led to widespread legislation giving a leg up to selected companies, projects and industries. The European Union, the U.S. and Japan embraced that argument with abandon. The results have been mixed, to put it gently.

The advocates of this revision may be disappointed by Western economies’ performance during the past 15 years, especially in terms of productivity and when compared to some Asian economies. Yet, these proponents somehow forget to mention that this period was also characterized by increasingly intrusive regulation and massive public expenditure in most Western economies, especially the U.S. Can industrial policies and “smart” regulations perform better? Or is it just old wine in new bottles?

Emphasis on trade barriers

The emphasis on trade suggests that the NWC policy vision would not rely so much on subsidies but instead on a mix of tariff and nontariff trade barriers, such as duties and licenses. That would appeal to the policymaker for several reasons.

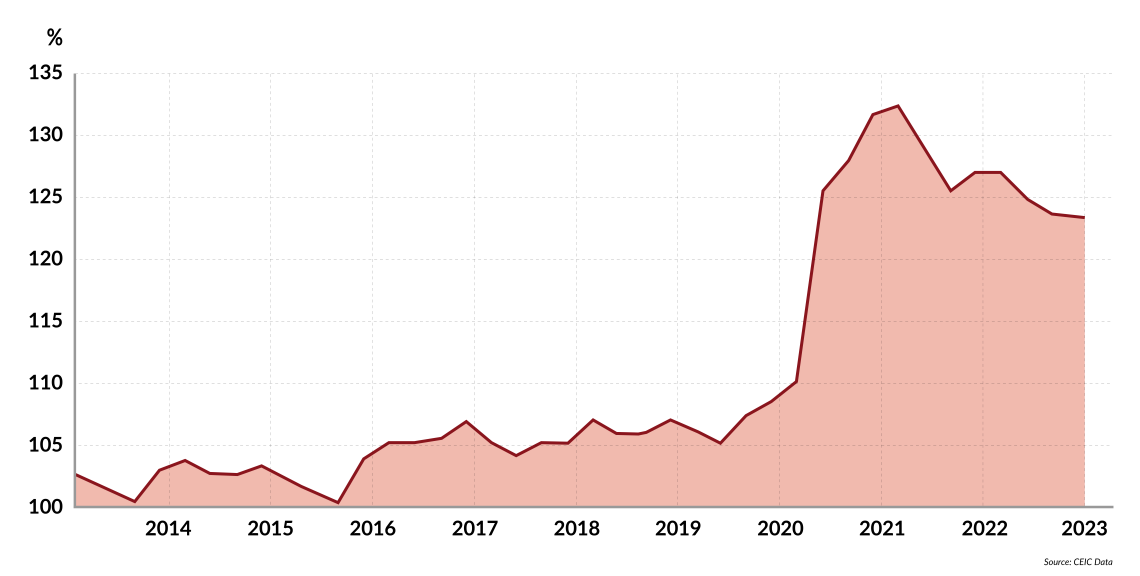

Given the parlous condition of many countries’ public finances, for example, they can hardly accommodate further significant public expenditure increases (the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio approached 123 percent early last summer).

Facts & figures

U.S. government debt, % of nominal GDP

Moreover, public opinion more readily accepts trade barriers, perceiving them as a reward to patriotic producers and a cost inflicted upon foreign, possibly unfriendly exporters.

Finally, such measures do not require that an omniscient bureaucrat predict scientific developments and risk taxpayers’ money by picking future winners. Instead, public expenditure would focus on “infrastructure.” Competition would still be the name of the game for the rest of the economy but harnessed by a commercial regulatory framework aiming to encourage and reward the righteous who contribute to high-tech-driven growth and national security.

From the Biden team’s viewpoint, the benefits of free trade have been overestimated.

This vision amounts to a gravestone to the WTO and all post-World War II efforts to promote free trade. The NWC is feasible only for very large countries or highly integrated blocs of countries. The cost of strategic autarky would be intolerable for a small economy.

Imperative to contain rivals at all costs

The answers to these objections would be straightforward, Mr. Sullivan asserted in April. From the Biden team’s viewpoint, the benefits of free trade have been overestimated: the Western world is now facing challenges unknown to free-trade supporters of the past, and new challenges require new policies. In brief, the world is moving toward geopolitical blocs, and the NWC would ensure that the U.S. is not left behind.

China, the argument goes, has shown the way by combining high-tech policies with intercontinental political initiatives. The NWC reaction would include U.S. technological leadership with a Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) scheme that is as expensive as the Chinese Belt and Road project but allegedly “transparent, high standard, inclusive and sustainable.”

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Will the NWC come true, and if so, what can we expect? To repeat, there is nothing “new” here. During the past 15 years, the ratio between world trade and world GDP has slightly declined (it is currently about 57 percent) interrupting a very long trend: the ratio was 25 percent in 1970.

Return of mercantilism

This phenomenon has little to do with supply shocks or disappointing results. Nontariff barriers have been on the rise all along. Heavy government regulation has also been with us for quite some time. The regulatory burden continues to expand, and although business and growth are suffering, public opinion is asking for more redistribution rather than more economic liberty. In short, mercantilism has already returned, and the NWC does not change its essence. Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), French King Louis XIV’s finance minister and best-known mercantilism proponent, apparently has the last laugh.

Prosperity-killing side effects

No matter how the Biden administration slices or splits it, their approach will stifle entrepreneurial spirits, slow innovation and harm technological progress and growth. History shows assuredly that economic freedom, not strategic regulation, is the key to prosperity. The emphasis on national security and semiconductors does not alter the proposed policy’s destructive impact. Entrepreneurship does not depend on national security and the resources going to semiconductors may discourage innovation in other industries.

Of course, the NWC underscores the need to reduce an economy’s vulnerability where there are no safety nets against potentially hostile counterparts. There is no way to compare the cost of economic interdependence and that of mercantilism. After all, and this is the logic of the NWC approach, the role of government includes protection against foreign aggression. Protection requires technological autarky and dominance, and these must be accepted and attained whatever it takes.

Dissenters will be brushed aside, and U.S. allies will have to comply. However, one should not be fooled: all the other items mentioned in the manifesto – climate change, equality, good middle-class jobs – are eyewash. Climate change and inequality have little to do with the poor performance of American manufacturing. Changes in the atmosphere have been with us for millions of years, and the middle class is thinner and thinner because some in society advance while others are crushed by poor education, oppressing taxation and choking regulation.

Price system as an alternative

One may still wonder whether regulation and protectionism (or selected protectionism, as the NWC advocates would call it) are the only answers to geopolitical threats and a way to shield the U.S. or the West from eventual harm.

For example, could not the U.S. authorities in charge of national security operate according to market principles and abstain from regulating trade flows and industries? Could not they choose to purchase goods and services from companies with production facilities on the U.S. territory, pay high enough prices to persuade current and potential suppliers to innovate and accept given clauses, and possibly prioritize producers that are in a better position to honor their commitments should a geopolitical crisis break out?

In other words, there is no real need to tamper with international trade. The price system would work better – and offer more transparency – than regulation. More importantly, from a geopolitical viewpoint, the U.S. allies and other potentially friendly countries would not get the impression that the NWC is an attempt to force them to integrate into a bloc of opaque nature, the scope of which is possibly unlimited.

What is most likely to happen?

The likeliest scenario is that the NWC will see intense implementation. The American taxpayer will be expected to fund more infrastructure projects and possibly more government investments in strategic industries. At the same time, the NWC will make the WTO into an empty shell and create tensions within the Western bloc. Europe will suffer, and its high-tech investors will flow to America.

Moreover, the American approach is unlikely to win over many friends in developing countries. And what about China? Many of its high-tech industries have grown thanks to imitation, industrial espionage and penetration of the U.S. and EU governmental and private business information systems. It is unclear how the NWC will tackle the issue.

Much also depends on how the American electoral campaign will evolve. Perhaps the NWC is just an attempt to persuade the West to cooperate more effectively with the U.S. (the Russian sanctions have been a sour experience for Washington), and perhaps the U.S. free-market electorate will eventually wake up. But hopes are dim, and the silence of major international organizations – IMF, World Bank, OECD – does not bode well.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/new-washington-consensus/