Europe’s innovation problem: Failure to develop growth-enhancing breakthroughs

In July, the European Commission published its “European Innovation Scoreboard 2024” (EIS), “a comparative assessment of the Research and Innovation performance of EU Member States, other European, and selected third countries.” At first sight, the main results offer a somewhat comforting picture. The scoreboard, overall, shows that the European Union countries do innovate. In 2024, they are ahead of China and Japan, and while they still trail behind South Korea, they are steadily closing the gap with Canada and the United States.

Yet, other sources show a different picture. For instance, the economic growth in the EU remains sluggish, with high-technology exports making up around 19 percent of manufactured exports in 2022. For the same year, Germany stood at roughly 16 percent, lagging behind the U.S. (about 20 percent), China (approximately 27 percent) and South Korea (about 36 percent). High-tech exports refer to products that require substantial investment in research and development, spanning sectors such as aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments and electrical machinery. So, what should we make of these figures?

The difficulty with measuring innovation

Measuring innovation is complex and making good use of the results is even more challenging. The EIS considers a large set of variables, among which are the number of doctorates in science, the prevalence of digital skills, the amount of private and public investments in research and development-related activities, the number of patents and trademarks, the volume of high-tech exports and environmental sustainability. The countries under consideration are ranked based on aggregate total scores for each variable.

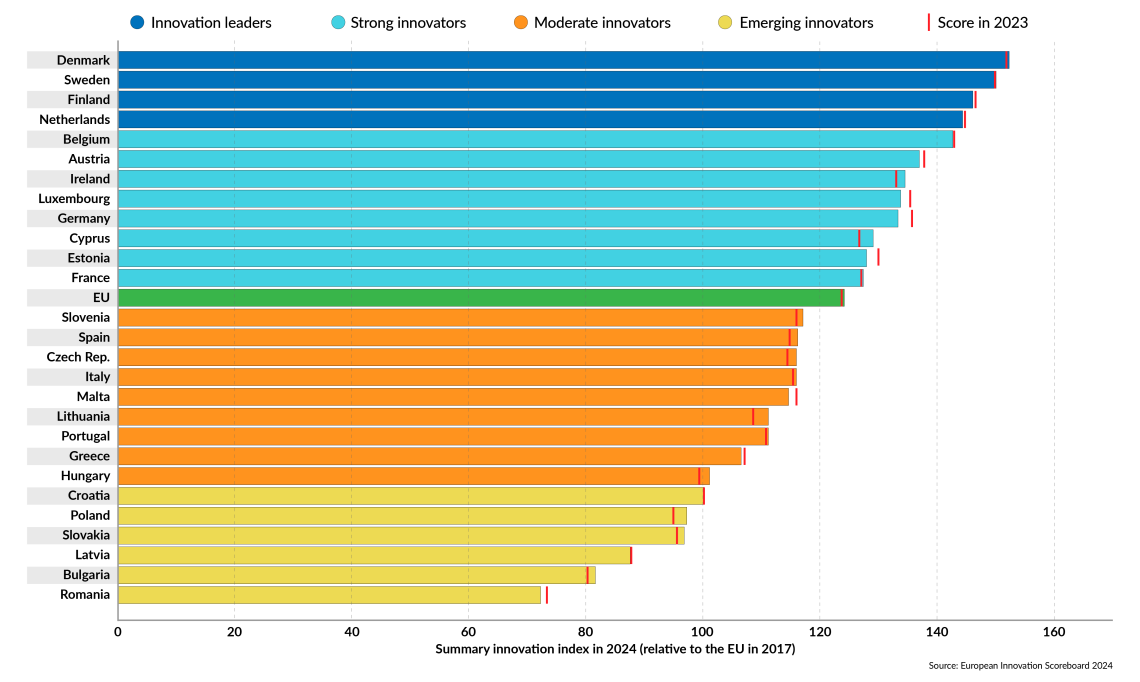

The Scandinavian economies dominate the EU list and have significantly improved their score over the years. Among the large countries, the innovation intensity in France and Germany is above the average but has made little progress over the past six years. According to the EIS, the leading countries within the EU have lost momentum, but Europe remains a strong innovator. The underlying message is that Europe does not suffer from dramatic structural problems and that its lackluster economic performance will improve before long.

Facts & figures

The EU’s innovation performance in 2024

The nature and purpose of innovation

To better understand the situation, it is helpful to distinguish two different lines of reasoning. One is the nature of innovation, and the other is the purpose of innovation.

In general, there are two interdependent categories of innovation, each characterized by different drivers. The key players in this first category are scientists, engineers, skilled craftsmen and designers. They drive innovation by creating new goods and services using the latest machines and technologies. In the past, the transition to high-quality steel or the advent of the microchip were such examples.

Entrepreneurs take center stage in the second set: They utilize the existing technical expertise to meet the demand for cost-effective production methods. For example, this happened with the transition from the workshop to the large plant or the global fragmentation of production processes. Moreover, entrepreneurs tap into available resources to address the needs that traditional producers have often overlooked. New products are created daily.

Three questions follow: What is the purpose of innovation and how much of it is considered optimal? What determines the presence of innovators? Do policies to boost innovation make sense?

Regarding the purpose of innovation, today’s rhetoric emphasizes two issues: security and economic growth. Many believe that defense requires high-tech equipment and relying on external suppliers poses risks. Therefore, domestic innovators are crucial to securing reliable, domestic high-tech equipment. We also often assume that innovation guarantees effortless growth. By this view, innovation is desirable and investing in it ensures that future benefits are available to the entire community.

Public discourse often mentions the above arguments, yet they are flawed. The argument about security is tempting. Policymakers are happy to promote expenditures, and countless domestic manufacturers are ready to pretend they are potential producers of high-tech military equipment and therefore eligible for subsidies. Meanwhile, the public is ready to believe that innovation in the military industry has significant benefits for civilian sectors.

However, helicopter money showered by incompetent policymakers on self-proclaimed defense innovators makes little sense. Successful innovation requires a vibrant entrepreneurial environment in which the military and civilian industries interact. Heavily subsidized laboratories and prototypes – “innovation” – hold little value if the entrepreneurial milieu does not guarantee that entrepreneurs can produce these prototypes on a large scale at reasonable costs, which they can update and improve over time. The ability to engage in adaptation and incremental innovation is often more important than the talent to produce scientific breakthroughs.

EU authorities will continue to highlight innovation only if and when it justifies or emphasizes the positive outcomes of the present expenditure programs.

One can say something similar about the link between innovation and growth. Growth depends on the efficient utilization of resources. Efficiency depends on competition and more generally, economic freedom. A competitive environment encourages innovation – acquiring new knowledge and entrepreneurial activities. Growth follows. The free market decides how much effort companies must devote to research and develop new knowledge, in which directions they must apply entrepreneurial talents, and how quickly they must react to their mistakes. The result is successful innovation. Failures to perceive and follow market signals amount to a waste of resources. This makes the notion of “desirable innovation” void.

Europe does keep its youth at school for longer periods, which perhaps has positive effects on the skills of its labor force and the generation of scholars. It may also succeed in enhancing scientific research and developing prototypes. However, these efforts do not necessarily imply competition and efficiency. They often fail to lead to growth-enhancing innovation, let alone military capability. The “social awareness” of the well-educated youth in Europe and the questionable results of the EU’s shift toward clean energy technology are prime examples of this.

Scenarios

Most likely: Overestimation of Europe’s role in global innovation

The most likely scenario stems from the relatively optimistic picture described by the EIS. From this perspective, EU authorities may think that the media vastly overestimate the danger that Europe’s contribution to global innovation and technological advances is declining. This complacent attitude will de facto kill the debate about what went wrong with European backwardness and stagnation and justify the current emphasis on sustainability, energy and digital transitions, traditional industrial policies and the fight against inequality. EU authorities will continue to highlight innovation only if and when it justifies or emphasizes the positive outcomes of the present expenditure programs.

Moderately likely: Resource reallocation to small and medium-sized companies

A somewhat likely scenario involves efforts to tackle the lack of innovation seriously. In line with EU tradition, this approach will divert resources from the existing major projects to finance innovative entrepreneurship, mainly focusing on small and medium-sized companies. While this may be politically tempting, it would prove useless and fraught with issues. The results would be modest at best, as subsidies hardly promote innovation. Small and medium-sized companies struggle to develop breakthroughs and transform them into marketable products and services. The strategy would also prove problematic, because de-financing the current grand projects is almost impossible. The commission would lose face and major business interests would go to great lengths to protect their current privileges and subsidies.

Least likely: Centralized regulation and lighter bureaucracy

A rather unlikely scenario draws on the recommendations of the so-called Draghi Report, named after its author, former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi. The report focuses on the poor performance of EU producers and advocates for increased spending, lighter bureaucracy and more efficient and centralized regulation. If the commission takes Mr. Draghi’s advice seriously, it will transfer more policymaking powers from the periphery (the authorities of EU member states) to the center (Brussels). Mr. Draghi (and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen) claim that more centralization will lead to better regulation and more effective enforcement. Of course, the commission will eventually deliver neither less regulation nor lighter bureaucracy since these elements are the very backbone of EU governance and the raison-d’etre of its vast and expensive apparatus. Innovation, therefore, will fall victim to centralized regulation.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/eu-innovation/