What’s going on with Milei-Caputo’s monetary policy?

Last December, when Milei became President of Argentina, his Minister of Economics, Luis Caputo, implemented a transitory plan to (a) clean up the central bank’s balance sheet and (b) remove all capital controls (cepo cambiario), paving the way for a more permanent monetary regime. It was implicitly suggested that by mid-2024, the transitory plan would have achieved its objectives. However, six months into the administration, the transitory plan has no expiration date, nor has the cepo been lifted.

This has disappointed many potential investors. The government has shifted from considering four to six dollarization reforms (as Milei claimed during the presidential campaign) to uncertainty about when the cepo will be lifted. Within this context, the last few weeks have seen a couple of significant events, including the release of the 8th IMF Staff Report and a notable increase in the money supply.

The IMF Staff Report

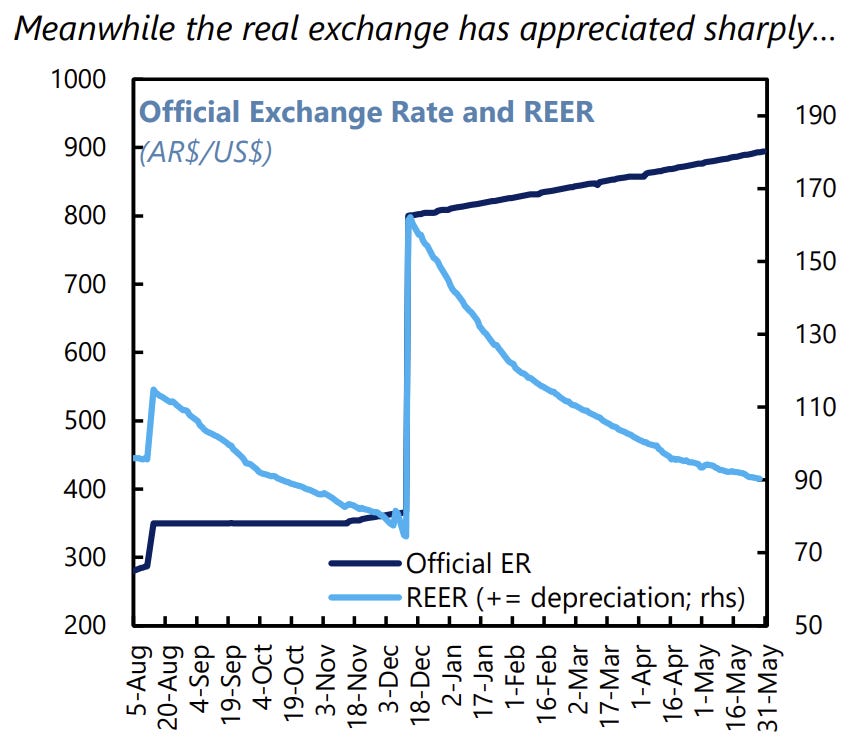

Milei-Caputo’s plan is raising serious doubts, as indicated by Argentina’s recent exchange rate volatility. The latest IMF Staff Report acknowledges that the government has met important objectives but warns of significant challenges ahead. Houston, we have a problem: your real exchange rate is on a clear path to becoming too appreciated. The depreciation gains from 400 ARS/USD to 800 ARS/USD in December are gone. The government’s acknowledgment that the central bank will lose reserves in the second half of the year is also concerning.

According to the IMF, “exchange rate policy should become more flexible to reflect fundamentals” (p. 2). The IMF observed a significant appreciation of the real exchange rate, as depicted in the report’s plot, with the real exchange rate consistently nearing the value recorded last December.

What was the government’s response to the IMF document? Milei went on TV to accuse the IMF of being a leftist organization belonging to the São Paulo Forum. For Milei, calling someone a “lefty” is a collection of insults, not just a descriptive statement. Caputo and Bausili (the central bank president) announced on Friday, June 28 (after financial markets closed, never a good sign) that they are not changing course. The government insists on maintaining a 2% monthly crawling peg while inflation is expected to stabilize at no less than 4% monthly for the remainder of 2024. Given Argentina’s need to receive more funds from the IMF, these reactions understandably create uncertainty.

On Friday, Caputo and Bausili announced their intention to finalize the transfer of central bank peso-liabilities to the Treasury through a new tool called the Regulatory Monetary Bills (Letras de Regulación Monetaria). However, they have not yet provided specific dates or details about this financial operation. It remains unclear whether the exchange of the bank’s liabilities to the new Treasury bills will be voluntary, “voluntary,” or mandatory.

The Monetary Base Incredible Expansion

Some economists are raising concerns about the growing monetary base. In response, Caputo dismissed these analysts as “intellectually dishonest,” speaking like a true politician.

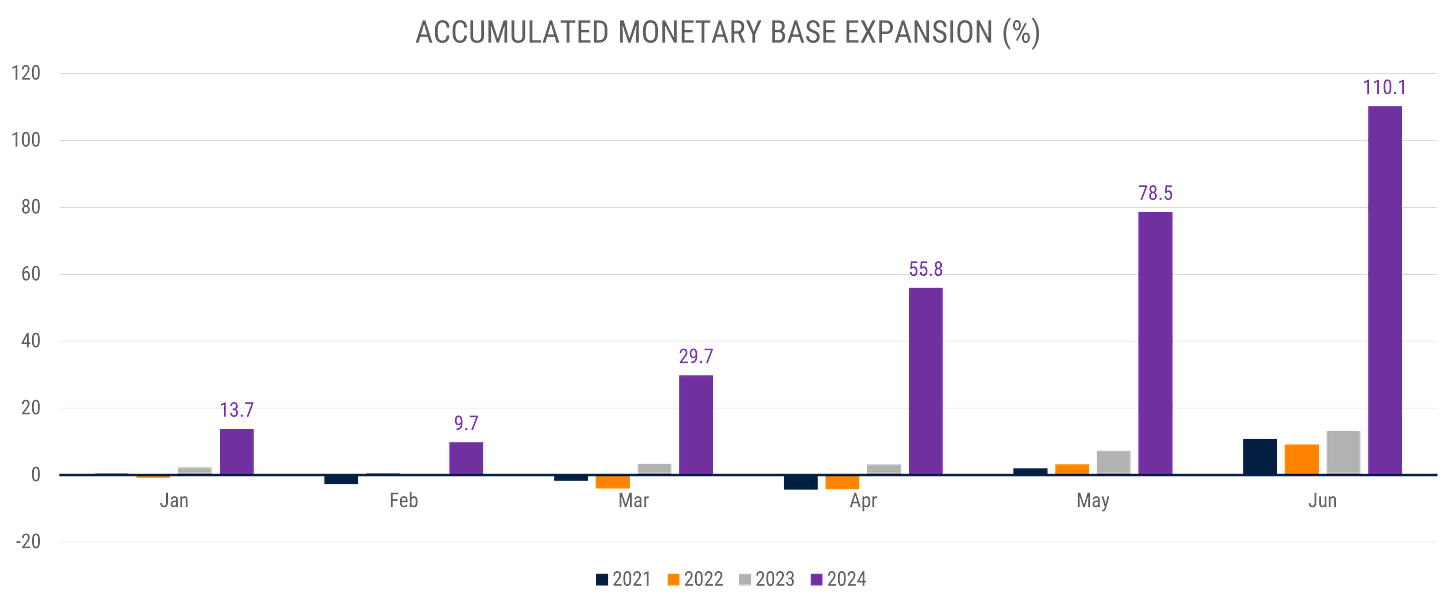

Let’s look at the numbers. The following plot shows the accumulated percent growth of base money starting in 2021. By June 2024, base money had grown 110.10%, a significantly higher rate than in previous years.

The government claims this is an expected result and not a cause for concern. This is the process in simple terms. The central bank issues pesos to pay off its liabilities as they mature. At the same time, banks use those pesos to buy newly issued Treasury bonds. As the newly printed pesos make their way to the Treasury, they become government deposits at the central bank, increasing base money (and decreasing other liabilities at the same time). The government argues this is not a concern because these new pesos remain in the Treasury’s account, reflecting an increase in money demand by the government. This effect can be observed on the central bank balance sheet. However, two qualifications are in order.

First, this is not the only reason for the increase in base money. Two other factors driving the growth of base money are (a) the central bank buying Treasury bonds to sustain their price (in April) and (b) the execution of puts.1

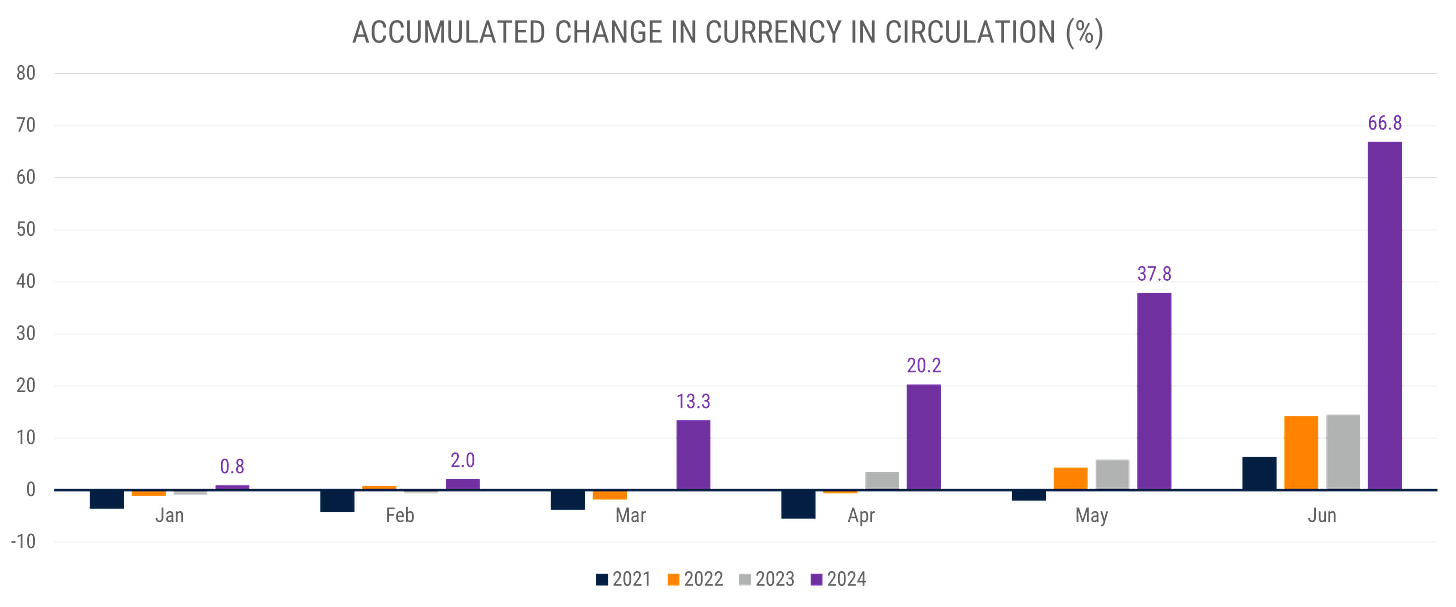

Second, currency in circulation (which is more than 50% of the base money) is also increasing rapidly.

It is doubtful that this is part of the Milei-Caputo plan. Regrettably, neither the Treasury nor the central bank has issued a document outlining the monetary plan. All we have are press conferences and TV interviews, which are not always clear on the details and, in my opinion, not always consistent.2

Even more confusing are Milei’s own words at the Llao Llao Forum (my translation and my emphasis):

The truth is, when you see our economic plan, which has a fiscal leg, a monetary leg, and an exchange rate leg, there is a nominal anchor; it is not true there is no nominal anchor. That’s another stupidity [from our critics]: ‘no, there is no nominal anchor here.’ Look, since we arrived [to the government], the monetary base practically shows no change, and we issued a lot [of pesos] to buy 12 thousand million US dollars, and [the previous government] left a little present called puts in the central bank that triggers an endogenous increase of money supply, and the also were the remunerated liabilities. How did we compensate for this? With the BOPREAL [bond] and budget surplus. As a result, the monetary base does not change. Today we have zero net reserves and the same monetary base. That is the anchor, the anchor is the quantity of money.

This talk is from April 18. By then, official numbers contradicted Milei’s statements. It is curious to see the government talk about “intellectual dishonesty.”

This material was originally published here: What's Going on With Milei-Caputo's Monetary Policy?