U.S. political divide turns tariffs into subnational economic challenge

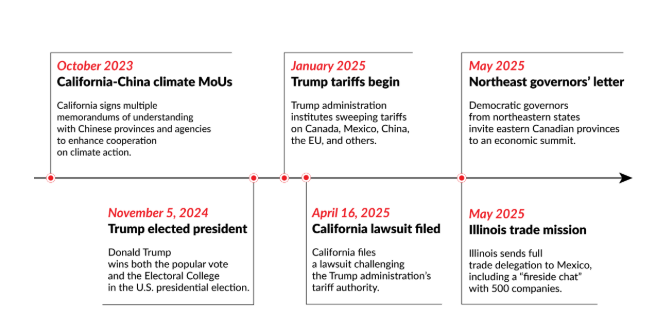

Uncertainty over tariffs and federal spending have characterized the first few months of the second Donald Trump presidency. Since taking office, the Trump administration has instituted various tariffs targeting Canada, Mexico, China, the European Union and countries worldwide. This saga has led to speculation about the prospect of an “External Revenue Service,” “to collect tariffs, duties and other foreign trade-related revenues.” United States tariffs have created uncertainty for international trading partners due to the breadth of affected industries, as well as frequently shifting exemptions and postponements.

Within the U.S., tariffs are unsettling states. At the federal level, the tariffs elicited attempts by Congressional Democrats to terminate the presidency’s powers to levy them. The U.S. Constitution grants tariff authority to Congress; however, several laws from the 1960s and 1970s effectively delegate some tariff powers to the presidency. States are generally restricted from engaging in external economic relations with other countries. Despite this, Democratic governors in California and Illinois have pursued independent economic policies that stretch constitutionality and increase uncertainty.

For foreign companies attempting to access American markets while maintaining financially viable supply chains, this polarization and constitutional tension is creating greater unpredictability. Rather than political posturing alone, subnational overtures to foreign trading partners made by states like California and Illinois represent meaningful economic dissonance between states and the national government. This increasing gap may also lead to growing subnational risks, as the U.S. begins to resemble a confederation in different issue areas.

How polarization creates subnational risk

Political polarization in the U.S. has deepened significantly over the past several decades. The American electorate has politically homogenized in different states and fractured at the individual level. In the 2009 book “The Big Sort,” journalist Bill Bishop documented how Americans have “self-sorted” into locales that match their sociopolitical values, and have coalesced into media spaces that align with their political orientation.

Beyond this geographic political homogenization into increasingly “blue” and “red” states and locales, which generally elect Democrats or Republicans, Americans themselves have become more isolated. Participation in civil society has decreased. In his book “Bowling Alone,” the political scientist Robert Putnam has documented that Americans’ involvement with in-person civic organizations, religious life and volunteer organizations has drastically decreased since 1960.

Polarization in the U.S. has not only increased since the 1990s, but has led to a shrinking population of ostensibly moderate swing voters. The Pew Research Center discovered in 2014 that 36 percent of Republicans viewed Democrats as a threat to the nation’s well-being, while 27 percent of Democrats held the same view about their Republican counterparts. This division has grown over the past decade, as studies have found that nearly half of voters from each party are now viewed as “evil” by their compatriots from the other major party. Research in the aftermath of the 2024 election found that 55 percent of left-leaning respondents now deem political violence acceptable. In the previous election, one study by the American Enterprise Institute found support for political violence among approximately four in 10 Republicans. While every study carries research biases, this data fits larger trends in the U.S.

Facts & figures: States as trade actors

As polarization has increased, so have states’ attempts to create carve-outs from national policy for their own interests. This dynamic has arguably proven most vivid with immigration. Eleven different Democratic-controlled states have attempted to establish themselves as “sanctuary” jurisdictions, limiting the ability of state and local authorities to cooperate with the federal government on illegal immigration enforcement.

Conversely, during the administration of former President Joe Biden, Republican states such as Florida and Texas took stronger stances on illegal immigration that put them at odds with the national government. Federal law not only makes immigration a federal purview, but the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause also ensures that federal power takes precedence over that of states. While immigration offers a vivid example of federal-state tension, this same conflict creates subnational uncertainty in economic policy.

The subnational risk of economic divergence

Rising tension between states has created drastically differing business environments. Red states like Florida, Texas and Tennessee not only currently have no state income tax, but also rank highly for attracting Americans from other states, while blue states such as California, New York and Illinois with relatively high state taxes are losing residents due to cost of living.

This dynamic is not confined to individuals, but includes businesses. California, which has the biggest economy of all states in the U.S. and if measured as a stand-alone country would be the fourth-biggest economy in the world, has famously hemorrhaged major businesses since 2020, with many fleeing to Texas and other business-friendly states with lower costs and less regulation. Amid the rollout of tariffs in the new Trump administration, moves by California and Illinois to signal economic independence from the federal government create potentially costly gray areas of legality.

The Constitution reserves for the federal government the sole authority to make economic agreements with other countries, which makes actions by Illinois, California and Democratic states in the northeast particularly provocative.

In each case, Democratic states made economic overtures to foreign trading partners in Canada, Mexico and China. In California, which is home to three of the largest ports in the U.S., Gavin Newsom’s gubernatorial administration sought exemptions for the state’s industries and began searching for ways to strengthen international trade ties despite national tariffs. After declaring that “California is not Washington, D.C.,” California launched a lawsuit against the federal government under the assertion that the Trump administration lacks tariff authority. California is a standout case, as the governor has made collaboration with China in the area of climate change policy a priority in subnational diplomacy.

In the Midwest, Illinois has blurred constitutional boundaries by sending a full trade delegation to Mexico as a response to federal tariffs. With bilateral trade amounting to about $32 billion annually, the mission by Illinois Governor JB Pritzker included a “fireside chat” attended by representatives from 500 different companies.

While framed by the Trump administration’s tariffs, Illinois has fostered unilateral trade ties with Mexico since 1989, when it opened an office in Mexico to foster investment in the state. From a diplomatic vantage point, Governor Pritzker’s trip carried the weight of full foreign diplomacy with its inclusion of multiple CEOs and officials from the Illinois state government.

More recently, Democratic governors from states in the northeast, including Massachusetts and New York, wrote an official joint letter to six eastern Canadian provinces to invite them to an economic summit in Boston. The letter itself falls short of an invitation to formal discussions about economic treaties, something effectively forbidden to states by the Constitution, but does mimic the rhetoric of independent countries. The letter calls for a recognition of mutual “interdependence” and alludes to “centuries-old familial and cultural bonds that supersede politics.”

For foreign companies attempting to interpret seemingly mixed signals from the Trump administration and different states, these gestures add uncertainty on the surface. However, these federal-state tensions are normal in the context of American history even if they are exacerbated by political polarization. To be sure, states’ rights issues permeate American political discourse routinely, with red states being the antagonists, for example, when seeking to weaken federal authority in areas of the so-called “culture wars” regarding abortion, separation of church and state, education and more.

States challenging America’s federal government through history

From 1776 until the Civil War, a coherent “national” commercial policy was often difficult to discern. Aside from tensions between states and the federal government over slavery, fierce disagreement predominated over trade and finance. Before the 1789 ratification of the constitution, states often engaged in their own mutual tariffs and trade wars as independent states. The question of whether states had the authority to manage trade and forge agreements with foreign powers was ultimately addressed through judicial review.

The 1824 Supreme Court case of Gibbons vs. Ogden helped solidify federal supremacy in commerce while effectively negating state-backed monopoly. On the issue of relations with foreign governments, the 1840 Supreme Court case of Holmes vs. Jennison determined that official agreements between states and foreign countries were prohibited and remained the domain of Congress.

Notably, the 1994 Supreme Court case of Barclay’s Bank PLC vs. Franchise Tax Board found that as a state, California could exact additional taxation on foreign corporations in the absence of federal prohibition. The 1994 case is noteworthy given that Barclay’s argument revolved around the assertion that state taxes on foreign investment precluded national coherence on the part of the federal government.

For foreign countries and businesses asserting whether state efforts to circumvent or puncture the Trump administration’s tariffs, historical and legal precedent does not offer much clarity. Thus far, Democratic states have not signed overtly formal trade agreements with foreign governments despite the diplomatic theater. At the same time, state assertions of authority that conflict with federal law have led to tensions in other areas such as immigration, and famously came to outright hostility and violence over slavery during the Civil War.

Polarization helps fuel these conflicts, particularly as the politics of spite have spilled into the domain of policy. The 2024 election results give some hope for more unity, since Donald Trump won both the popular vote and the Electoral College.

Scenarios

Most likely: Federal supremacy and state level divergence

Historical precedent on tariff fights favors the federal government, despite underlying polarization between Democrats and Republicans both electorally and within government. The constitution makes federal precedence clear on paper, while Democratic states seeking to contest the tariffs lack the force to challenge Washington on the ground over tariff enforcement.

Indeed, such an open confrontation is more likely in an area like immigration than on tariffs. Domestically, states present increasingly divergent economic environments, posing additional considerations for foreign investors in the U.S. such as California’s automotive emissions standards that surpass federal limits and often set a stricter informal benchmark that automakers then apply to the entire country. This is much like what faces American firms operating in neighboring states abroad under varying trade conditions within trading blocs such as the European Union or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Examining the actions of Democratic states over the duration of the tariff saga to date, it is noteworthy that no formal agreement between a governor and foreign power has occurred. No free trade deal has been negotiated. While California has signed memoranda of understanding with China on climate change, these are different from binding formal treaties.

Similarly, Illinois’ large-scale trade delegation to Mexico is arguably more of an effort to reinforce existing business relations despite tariffs rather than to collaborate on circumventing them. Such meetings are useful for strategizing on lobbying the federal government to alter tariff stances and create specific carve-outs for key industries.

In sum, while there is little evidence of states attempting to escalate to open conflict with Washington over tariffs, states themselves will present increasingly disparate subnational economic environments for companies looking to invest or expand within the U.S.

Less likely: De facto confederation over time

There is a historical argument to be made for increasing confederation in policy over time if political polarization continues to grow and officials at the federal and state levels decide to pursue punitive measures or legal action against one another. Until the Civil War, America’s currency area was chaotic at best, with states and banks issuing their own notes and businesses looking to the Mexican silver peso for price stability.

Laws passed during the Civil War, such as the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864, standardized American banking and currency and brought financial coherence to the U.S. as part of larger efforts to cement federal precedence over state authority. These laws were part of a national attempt to economically break the Democratic-led Confederacy during the Civil War, and settle multiple conflicts about state authority alongside the principal question of slavery.

Political polarization has grown in the U.S. over the past several decades due to sociological changes and technological advancements. While these shifts have led to greater differences in economic performance and business environments among the states themselves, these tensions are playing out in multiple policy areas rather than being concentrated on a single issue such as slavery in the 19th century.

Despite the tumult of the past eight years, which included differences in the Covid-19 pandemic response, ideological splits on immigration and social issues, and riots during 2020-2021, no formal efforts have been made toward confederation. Ironically, these divisions are arguably hindering the emergence of a confederation due to Democratic and Republican efforts to cement power nationally and electorally rather than to separate or construct state autonomy. For these reasons, confederation is a less likely scenario.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/tariffs-polarization/