The quantum race is on — and Europe can’t afford to lose again

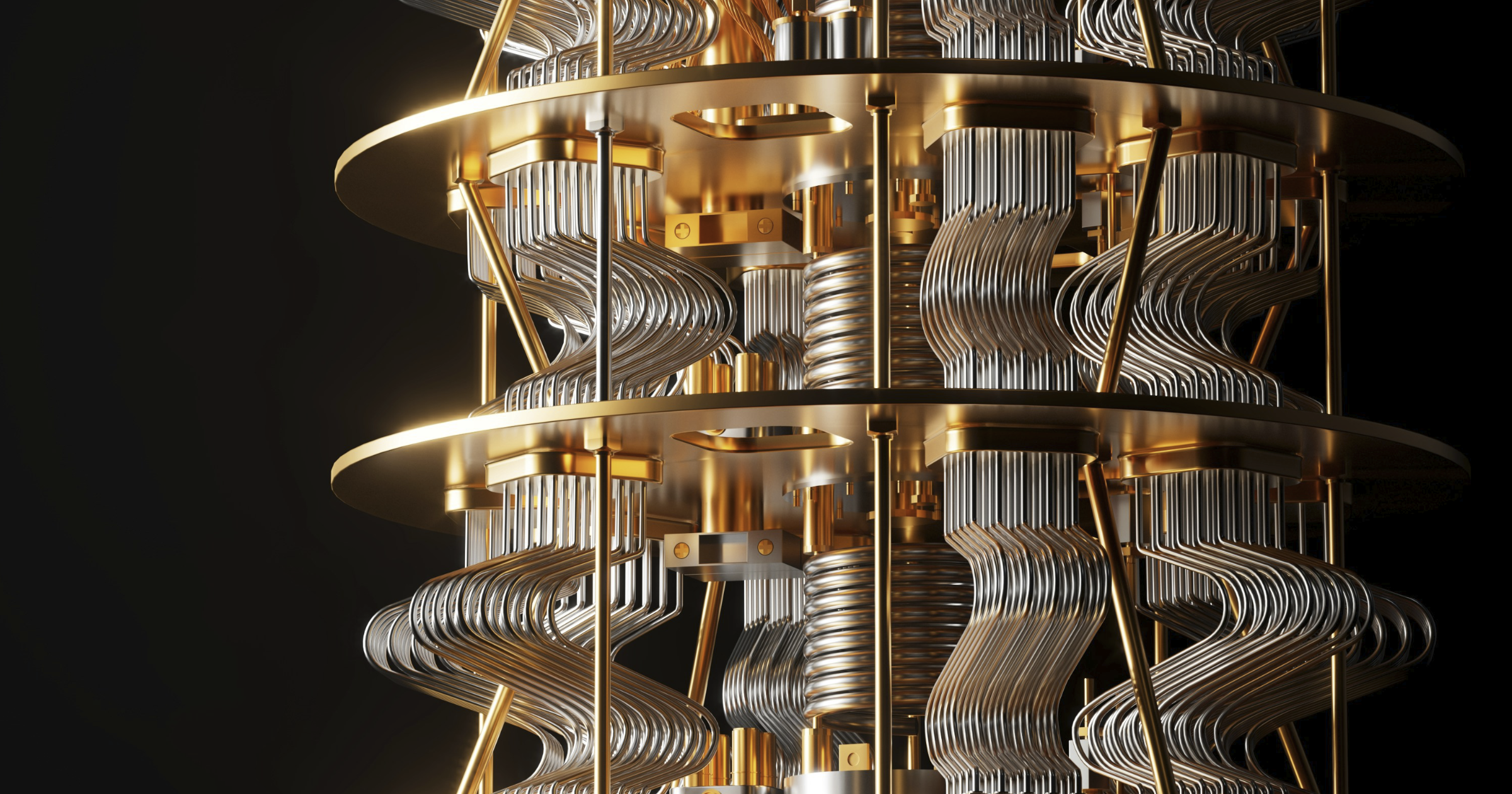

Europe once again stands at the edge of a technological revolution—this time, in quantum computing. Widely regarded as the next tech frontier, quantum promises capabilities far beyond today’s supercomputers, with applications in drug discovery, battery development, communications, navigation, defense, and cybersecurity. As the United States and China race ahead in artificial intelligence, Brussels sees quantum computing as its second chance to lead the next digital wave. The stakes could not be higher; quantum technologies are rapidly transitioning from theory to real-world applications.

To seize the opportunity, the European Commission has launched an ambitious Quantum Strategy, pledging to make the EU a global leader in quantum by 2030. Yet the plan relies heavily on top-down programs—public funding, flagship initiatives, export restrictions—the same central planning that has long undermined Europe’s competitiveness by favoring uniform directives over innovation.

Instead of unlocking entrepreneurial potential, Brussels risks stifling progress through complex regulations and bureaucracy, which can discourage experimentation and slow startup growth. If Europe does not change course, it could once again fall behind—turning its quantum leadership opportunity into a lost one.

Why Europe Risks Falling Behind

Europe is already a global powerhouse in quantum research. Its universities and research centers consistently produce world-class work, with 34 of the world’s top 100 quantum computing universities based in the EU, just behind the U.S., with 37. Yet this scientific strength has not translated into market success. Europe captures only 5% of global private investment in quantum technologies, compared with over 50% in the U.S. and 40% in China. As a result, many of Europe’s breakthroughs are commercialized abroad, with startups relocating to countries where capital and scale are more easily secured.

This isn’t just about quantum. We’ve seen this story before. Europe played a pivotal role in the development of AI, yet Silicon Valley and Chinese giants now dominate the field. Of the world’s ten most powerful AI companies, eight are American, one is Chinese, and one is Vietnamese—none are European. This demonstrates that while Europe excels at discoveries, it struggles to scale them into global businesses.

Several structural challenges help explain this persistent gap. First, Europe’s tendency to regulate emerging technologies too early and too aggressively stifles innovation. In AI, for example, sweeping rules were imposed before many European firms had even entered the market, while U.S. and Chinese competitors surged ahead. As a result, over 80% of global AI investment now flows to the U.S. and China, while Europe captures just 7%. If policymakers repeat this mistake, quantum could meet the same fate.

Second, Europe’s capital markets remain fragmented. U.S. startups can raise $100 million from a single fund. European founders, by contrast, must patch together financing from multiple national and EU programs, making it hard to scale. As a result, many promising quantum firms have relocated to the U.S., where private investment tripled last year, while in Europe, it fell by 40%. The shortage of European venture capital capable of leading large rounds leaves the continent’s quantum sector financially vulnerable.

Third, talent is a critical bottleneck. Europe trains world-class quantum researchers, but many are tempted to leave for higher pay and better opportunities abroad. Today, Europe has only a third as many quantum-skilled professionals as the U.S., with only one qualified candidate for every three quantum job openings. Europe risks a ‘quantum brain drain’, where its top talent moves abroad instead of fueling the next wave of technological innovation.

Underlying all these challenges is a more profound issue: Europe’s overreliance on central planning. The EU’s Quantum Strategy reflects this mindset, favoring bureaucratic direction and government subsidies over market dynamism. Some member states have gone further, imposing export restrictions on quantum computers—a move industry leaders warn will stifle collaboration and slow innovation. Central planning has never produced global tech champions, and there is little reason to believe it will now.

Stop Planning, Start Enabling

If Europe wants to lead in quantum, it doesn’t need more industrial strategies—European bureaucrats need to get out of the way. That means cutting red tape, lowering taxes, simplifying access to capital, and making it easy for startups to hire and expand across borders. Most importantly, Europe must embrace a culture that celebrates risk, rewards results, and lets competition decide what technologies succeed.

The potential is enormous. Quantum computers could one day crack current encryption, process vast datasets in seconds, and design new drugs in minutes. Some forecasts estimate the sector could generate up to €780 billion in value over the next 15 years. But this value won’t be captured by those who write the best strategy papers. It will go to the countries that build ecosystems where bold ideas can flourish, scale, and evolve into global companies.

Europe has the science and the researchers. What it lacks is freedom for innovators to build, compete, and thrive. Without that, the continent risks being confined to the laboratory: producing breakthroughs, while others turn them into successful industries.

The quantum race won’t wait. If Europe doesn’t act now, its next missed opportunity could be its most costly yet.

This material is a result of a new collaboration between the Institute for Research in Economic and Fiscal Issues (IREF) and the European Center for Austrian Economics Foundation (ECAEF), focused on publishing a series of articles on economic and fiscal topics. It emphasizes our commitment to independent thought, academic freedom, and critical inquiry. The original was published here: https://en.irefeurope.org/category/publications/online-articles/