The EU’s moderate reindustrialization strategy

Over the past two decades, the European Union has experienced deindustrialization (a reduction in industrial capacity), partly due to the shift of manufacturing overseas, which has created strategic vulnerabilities. This issue is particularly pronounced in essential sectors such as batteries, semiconductors, renewable energy, aerospace and defense. The Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also exposed deep supply chain dependencies on China and other third countries.

Persistent contraction in manufacturing

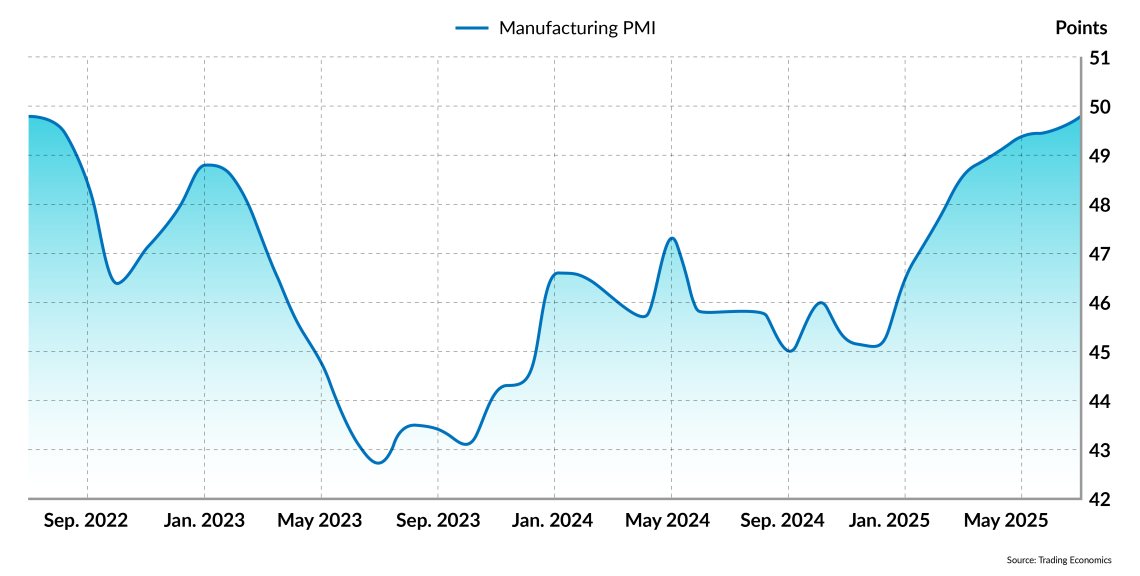

In the face of these trends, the EU has encountered a worrying long-term decline in manufacturing activity. This is primarily reflected in the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) surveys, which serve as forward-looking economic indicators. Furthermore, monthly production data, which reflects past performance, shows a continued downturn across the region.

The Eurozone Manufacturing PMI, compiled by S&P Global, is derived from monthly questionnaires sent to a panel of manufacturers across Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Austria, Ireland and Greece, covering about 3,000 private sector companies. It was in a state of contraction from July 2022 to June 2025.

Germany, the industrial powerhouse of the bloc, has been particularly hard-hit. Its manufacturing PMI surveys have remained in the 40-45 range from early 2023 through early 2025. This figure is notably below the neutral threshold of 50 (indicating neither growth nor contraction), highlighting a downturn in industrial production. Similarly, the manufacturing PMI for the entire EU has remained under 50 throughout much of 2023 and 2024, pointing to a contraction across the trading bloc and signaling a decline in industrial production.

Even though services often absorb jobs lost in manufacturing, they tend to be in sectors with low productivity.

However, it is worth noting that since June, the manufacturing sector in the eurozone has begun to show tentative signs of recovery. The Manufacturing PMI rose slightly to 49.5 in June from 49.4 in May, marking its highest level since August 2022. Still, it has remained below the crucial 50 threshold for the 29th consecutive month.

According to Eurostat, in 2024, manufacturing accounted for 19.7 percent of the gross value added (GVA) generated in the German economy, and about one-third of the contribution from services. Additionally, Germany’s industrial sector is larger than that of other major EU economies, where on average, manufacturing accounts for only 15.6 percent of GVA across the European bloc.

In 2024, the proportion of GVA generated by manufacturing in other European manufacturing centers was 16.6 percent in Poland, 16.3 percent in Italy, 11.7 percent in Spain and 10.6 percent in France. Manufacturing generates approximately two-thirds of total factor productivity growth in the EU. As a result, even though services often absorb jobs lost in manufacturing, they tend to be in sectors with low productivity. The qualitative effects of deindustrialization on employment and economic growth could be more damaging over the long term as productivity declines or stalls.

Manufacturing jobs are also more stable and better paid on average than those in other sectors of the economy. Monthly earnings for manufacturing workers are 5 percent higher than the general average in the EU.

Manufacturing is vital to Europe’s economy in several other ways. It accounts for over two-thirds of EU exports and two-thirds of the financing for total private sector investment in research and development (R&D) across the continent. Manufacturing therefore serves as a powerful engine for growth, providing higher-quality jobs.

Facts & figures: The EU’s Manufacturing PMI

In contrast to the contraction presented in recent years’ PMI data, the long-run value of manufacturing production in the EU has increased significantly, rising from 1.3 trillion euros in 2000 to over 2.7 trillion euros in 2023, according to the World Bank. Yet, from 2008 to 2023, the EU lost 2.3 million manufacturing jobs, according to the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), with Germany alone losing 200,000 jobs in 2023 due to high operating costs and weak demand.

The ETUC claims that the full scale of this employment decline is obscured by short-term contracts and reduced hours, which could indicate as many as 4.3 million manufacturing jobs have been lost since 2008. Clearly, these developments are part of a broader long-term trend in advanced economies.

Nevertheless, manufacturing employment provides a positive boost to the rest of the economy. Research conducted at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre shows that for every job created in manufacturing, up to two additional jobs are created elsewhere in the economy.

This multiplier effect is even greater in innovative high-tech sectors. For every new software designer, five additional jobs are generated in the supporting services ecosystem. Creating jobs in advanced high-tech industries enhances capabilities, leading to a virtuous cycle of innovation and investment that can maintain high living standards in advanced economies.

U.S. and China’s state-led industrial policies

The United States and China have adopted distinct but increasingly assertive approaches to support their domestic manufacturing sectors through government-led policy initiatives. Both countries recognize manufacturing as critical to economic resilience and global competitiveness, and they have intensified their industrial policy efforts in recent years.

The U.S. has seen a marked shift toward more proactive industrial policy, driven by concerns over supply chain vulnerabilities and economic competitiveness with China. The passage of major legislation in 2022 such as the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides subsidies for the green industry, represented a pivotal shift in the country’s industrial strategy.

These laws provided substantial support totaling hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies, tax credits and R&D funding aimed at bolstering domestic manufacturing in critical sectors, particularly semiconductors, clean energy and advanced technologies.

In a radical overhaul of these policies, which were introduced under the Biden administration, U.S. President Donald Trump has touted tariffs as an alternative and more effective means of driving widespread investment in American manufacturing. He has also aimed to secure several hundreds of billions of dollars in direct investments from agreements concluded with allied trade partners such as the EU, Japan and South Korea. These investments would be channeled into revitalizing the U.S. strategic industrial base, including semiconductors, critical minerals, energy infrastructure, pharmaceuticals and shipbuilding.

Mr. Trump has promoted his tariff and inward investment dealmaking policy alongside domestic deregulation and tax cuts, arguing that these measures will further stimulate investments, leading to significant job growth in the manufacturing sector and enhancing domestic technological prowess. Although economists have expressed concern about tariff-induced price hikes for U.S. consumers, President Trump has reiterated that any short-term pain will be worth the long-term economic and industrial gains.

In China, Beijing has long relied on state-led industrial policy as a central mechanism for guiding economic development. Major initiatives include Made in China 2025. Launched in 2015, the program aimed to advance China’s position in the global value chain by promoting domestic innovation. It also sought to reduce reliance on foreign technology in 10 priority sectors, such as robotics, aerospace, electric vehicles and semiconductors.

Under this model, state-owned enterprises, local governments and state-backed investment funds have played key roles in achieving policy objectives. The Chinese government has also allocated substantial funding toward infrastructure, R&D and expanding manufacturing capacity. While these initiatives have enabled rapid industrial upgrades, they have also faced criticism for disrupting global markets and compromising fair competition.

Both the U.S. and China are increasingly prioritizing the reduction of external dependencies and securing of technological leadership. This has driven a broader trend of “de-risking” and selective decoupling in global supply chains.

Reindustrialization as an economic imperative for the EU

The EU’s manufacturing slump, as indicated by PMI data in Germany and the broader eurozone, arguably signals a deepening structural decline. To slow the pace and scale of deindustrialization, the EU has launched one of its most ambitious efforts to restore industrial capacity in strategically important areas. The measures, which collectively serve as tools for import substitution and are framed around the concept of “open strategic autonomy,” are integral in developing a moderate and gradual reindustrialization policy.

Regarding supply chain resilience, the EU’s post-pandemic industrial strategy focuses on reducing dependence on foreign suppliers, especially in critical sectors like pharmaceuticals, semiconductors and clean energy technologies. To achieve this, the Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe of 2020 and the European Chips Act of 2023 aim to increase domestic production capacity, minimizing disruptions caused by external shocks.

The EU is likely reshaping its industrial landscape toward a more self-reliant and increasingly protectionist future.

The European Green Deal, although primarily an environmental policy, acts as a de facto industrial strategy by directing investments toward sustainable technologies and reshoring production. Key elements include the Net-Zero Industry Act of 2023, which establishes benchmarks for EU-produced clean tech, aiming to produce 40 percent of the bloc’s renewable energy equipment locally by 2030. It resembles U.S. subsidies under the IRA, though with less direct financial support.

Meanwhile, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) levies tariffs on imports of carbon-intensive goods such as steel, cement and aluminum. CBAM shields EU industries from cheaper, high-emission foreign competitors while incentivizing low-carbon production within the eurozone.

The Green Deal serves dual purposes: advancing climate goals while strengthening the EU’s industrial base through targeted subsidies, regulatory incentives and trade protections.

Similarly, public procurement rules have increasingly favored an “EU-first” approach in strategic sectors. The International Procurement Instrument of 2022 allows the European Commission to restrict third country access to EU member government contracts.

The latest iteration of an EU-first policy is the new Security Action for Europe. The 150-billion-euro defense fund includes a strong “buy-European” requirement. Non-EU suppliers can only be included sparingly and conditionally, depending on formal partnership agreements. For instance, the recent EU-U.S. trade deal may see the bloc acquire more weapons from the U.S., although no specific amount was affirmed for potential purchases of American defense equipment.

The EU has also implemented stricter and more comprehensive trade defense policies. These include anti-dumping and anti-subsidy measures, especially targeting Chinese imports in sectors such as electric vehicles and solar panels. Its most prominent policy tool in this area is the Foreign Subsidies Regulation of 2023. This legal instrument examines foreign state-backed companies that distort the EU market, thereby indirectly protecting domestic industries.

The Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), adopted in 2023, is arguably a cornerstone of the EU’s reindustrialization agenda. It aims to secure access to minerals essential for green and digital transitions, such as lithium and rare earths, by reducing reliance on China (which supplies 98 percent of the EU’s rare earth imports) and other non-EU countries.

The CRMA mandates that by 2030, the EU extracts at least 10 percent of its annual consumption of critical raw materials, processes 40 percent and recycles 25 percent. This decreases dependence on foreign suppliers while fostering domestic mining and refining industries. By ensuring stable access to critical inputs, the CRMA reinforces the EU’s industrial base, particularly for green technologies like batteries and wind turbines, where raw material dependencies pose a strategic risk.

Lastly, in April, the European Commission launched an automated “import surveillance” system that monitors monthly trends in volumes and prices to identify product surges and signal potential trade diversion from high-tariff markets. Launched amid global trade turbulence – namely U.S. “reciprocal” tariffs and Chinese counter-tariffs – the tool addresses genuine redirection risks.

While the import surveillance tool is presented as a transparency-enhancing and data-driven measure, its critics warn of a real risk of leaning toward protectionism. The swiftly implemented tariff pipeline, arising from the tool’s operations, could effectively bring back trade barriers disguised as technical surveillance, which may ultimately undermine the principles of a free market.

Considering these measures, the success of the EU’s piecemeal approach to reindustrialization depends on balancing open trade and strategic self-sufficiency. Nevertheless, the EU’s policies show that reindustrialization is being pursued through regulatory and investment frameworks rather than tariffs and unpredictable trade ultimatums. In doing so, the EU is likely reshaping its industrial landscape toward a more self-reliant and increasingly protectionist future.

Scenarios

Most likely: The EU continues its policy of moderate reindustrialization

The EU is moving toward reindustrialization, but it is shaping up to be a distinctly European approach – more cautious, focused on climate and guided by regulations. While it may not be as radical or brazen as the U.S. strategy, key sectors such as green technology, semiconductors, defense and raw materials will increasingly receive targeted support. Therefore, one can expect an evolution in its approach, not a revolution.

For example, the EU has recognized the challenges posed by China’s heavily state-interventionist trade and industry policies. However, it is unlikely that Brussels will adopt the aggressive and broad approach that Washington has taken in imposing arbitrary tariffs on its trading partners. Nor is the EU likely to pursue trade agreements to pressure third countries into excluding Chinese entities from their international supply chains. However, the extent to which the EU complies with Washington’s requirements on economic security vis-a-vis China as part of their trade deal will be telling.

The reasons for the EU’s more nuanced approach are twofold.

First, the EU, as a collection of supranational bodies and a multi-member trading bloc with legitimacy rooted in a consensus-based and rules-driven system, is predisposed to supporting a global trading system built on a shared acceptance of rules.

Second, while some factions within the EU may support a more interventionist and confrontational stance toward China, these perspectives are not the majority among member state governments or within key democratic institutions, such as the European Parliament.

At the same time, the EU will strive to establish new trade agreements that enhance market access with key partners such as India and China. If this access does not materialize, the EU will probably implement targeted restrictive measures.

Less likely: The EU adopts a more radical U.S.-style of reindustrialization

It is not yet certain whether the EU will continue a nuanced and segmented approach to reindustrialization in the long term. Rising populism and concerns about deindustrialization, particularly in France, Germany and Italy, are prompting governments to adopt more proactive industrial policies. There is increased focus on protecting manufacturing sectors that have largely lacked state support for decades.

Election results across the EU, from the largest countries to the smaller ones, show that a post-World War II political centrist order is fragmenting. Amid this chaos, new radical ideas are increasingly becoming mainstream.

Many observers have speculated that President Trump’s reset of trading relationships and his focus on revitalizing the U.S. manufacturing sector stem from a distinctly individual approach. The hope is that these policies will not endure beyond his tenure, leading to a return to the post-war status quo that prioritizes liberal economics.

The years to come will reveal whether this materializes or if the populist wave that contributed to President Trump’s two electoral victories across the Atlantic will further penetrate EU member states. This movement may push for a more protectionist approach to trade and a stronger effort toward reindustrialization in Europe.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/eu-reindustrialization/