Russian geopolitics and European security

After United States President Donald Trump’s bilateral meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Alaska, a summit was held in Washington, D.C., with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy and the leaders of major European countries, NATO and the European Commission.

The staging of these meetings was already significant. Alaska, once Russian territory, sits where the U.S. meets geographically with the Russian Federation – and far from Europe. The symbolism was clear: two major powers were speaking directly, without the involvement of Europe’s middle powers. For Mr. Putin, this was highly important. He has never forgotten former U.S. President Barack Obama’s unfortunate 2014 remark that Russia was just “a regional power.” Restoring pride is necessary if one wants to lay the groundwork for a ceasefire without capitulating to all of Moscow’s demands.

Now Ukraine and its Western supporters face the dilemma of how to end the bloodshed without conceding too much. Ahead of the summit, Mr. Zelenskiy told European allies in Brussels: “We need real negotiations, which means we can start where the front line is now.” He and European leaders agreed that a ceasefire was the prerequisite for negotiating a final agreement.

For Europe, the only way to build an equitable neighborhood and long-term security is through credible deterrence.

The summit in Washington emphasized the importance of European unity, particularly regarding objectives and security guarantees, including the possible stationing of European troops in Ukraine. Negotiations are expected to follow.

It does not appear realistic that Russia can be forced to withdraw. European countries – despite their far larger economies and populations – lack the military strength to enforce it. The likely outcome is therefore a ceasefire roughly along the existing frontline, freezing the conflict and turning occupied territories into de facto, if not de jure, Russian holdings. Frozen conflicts, however, tend to become permanent.

Russian geopolitics

Russia’s geopolitical goals are simple in their broad objectives but complex in detail. The Kremlin seeks to maintain great-power status, push adversaries as far from its borders as possible and prevent foreign influence on internal affairs and culture.

The complexity lies in Russia’s composition and geography. It is a vast, multiethnic, multireligious country with the longest borders in the world, many of them shared with states of very different cultures and governance systems. With only about 140 million people spread across an enormous landmass, much of it sparsely populated, Russia is as much an Asian country as it is a European one.

Moscow has growing interests in Asia and the Arctic, priorities reinforced by Mr. Putin’s pivot east. Still, its ambitions in Europe remain crucial. Centuries-old fears of invasion from the West and restricted access to open seas have deeply shaped Russian strategy. This sense of destiny – whether as the “third Rome” or, in Soviet times, as the torchbearer of Marxist revolution – has often translated into territorial claims. This partly explains the invasion of Ukraine, and any “success” there will likely embolden further action.

A ceasefire will certainly include a “no-NATO” clause regarding Ukraine. Yet Russia’s ambitions extend further. Moldova’s breakaway region of Transnistria, on Ukraine’s western border, identifies with Russia and hosts Russian troops. Crimea has restored Russia’s position on the Black Sea, but it remains an inland sea.

In the Baltic, Russia’s situation worsened after Finland and Sweden joined NATO. Murmansk in the Arctic is now Moscow’s only free outlet to the Atlantic, but Russian ships disembarking there must make the long journey around the northern tip of Norway. Pacific ports like Vladivostok lie too far from Russia’s core population and industry to be viable alternatives.

For Moscow, limited sea access is not just an economic concern but a strategic military one, pushing it toward a stronger submarine fleet. Yet Russia still views Estonia and Latvia – former Soviet Republics that are now independent countries and NATO members – as vulnerabilities. Both lie close to St. Petersburg, Russia’s second-largest city and an economic hub. Moscow could eventually aim to reoccupy them, as well as build a land bridge to the Kaliningrad enclave wedged between Poland and Lithuania.

The Caucasus is another sensitive area. Georgia remains a priority for Moscow, which seeks to install client regimes there. Armenia and Azerbaijan are also critical, with Baku’s Caspian location and trade routes through Iran to the Indian Ocean giving it particular significance. Here, Russian and Turkish interests frequently clash.

Europe’s security dilemma

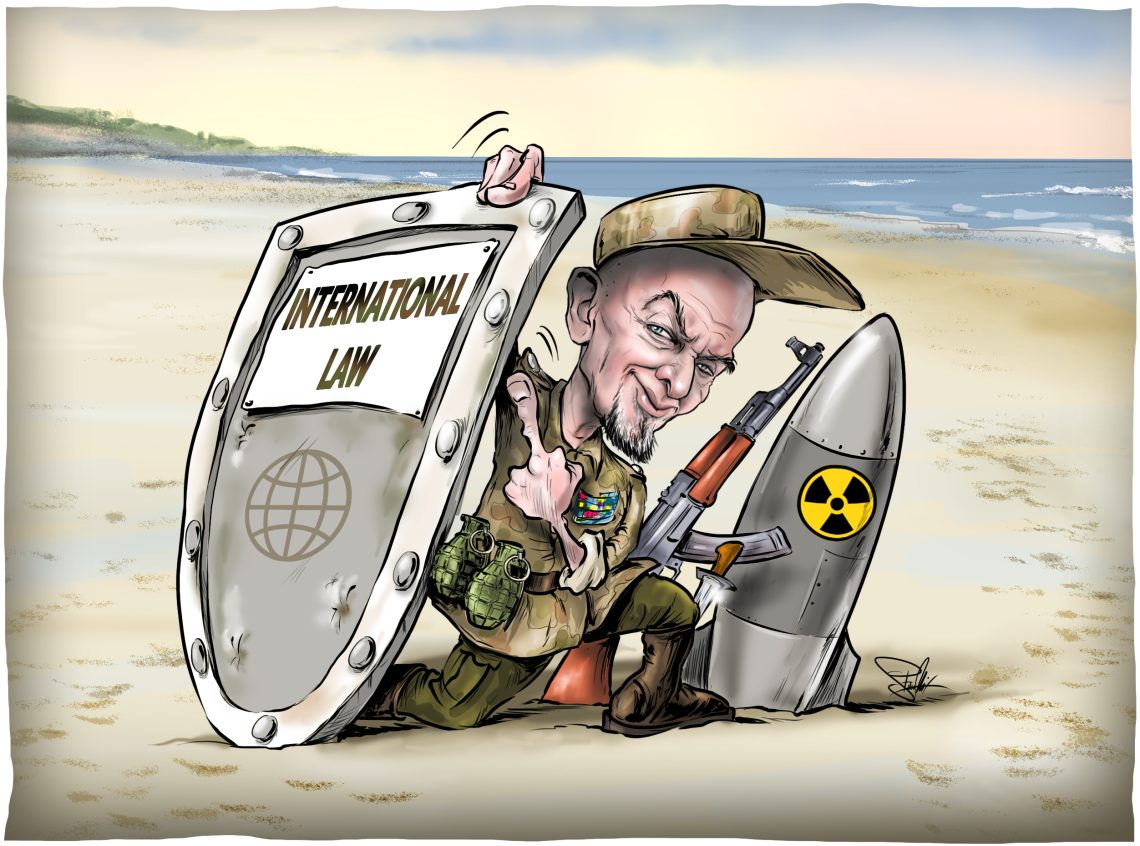

Russia’s geopolitical ambitions are not new, nor would they vanish even with a change of regime in Moscow (an outcome many in the West dream of). For Europe, the only way to build an equitable neighborhood and long-term security is through credible deterrence: strong defenses, coupled with a clear willingness to respond decisively to aggression, even abroad. Visible, harsh deterrent measures, even stronger than NATO’s Article 5, must be implemented. Europe’s weak, lukewarm response to Ukraine in 2022 can never be repeated.

Europe has nearly 500 million people compared with Russia’s 140 million, and its economic and industrial strength is roughly nine times greater. Yet power must be backed by resolve. At the same time, Europe should avoid interference in Russia’s internal politics while shielding itself from subversion.

This comment was originally published here: