What seizing Russian assets

could mean for the West

In a nutshell

- Conflict fatigue is prompting new approaches to fund Ukraine aid

- Seizing Russian assets could undermine Western currencies

- The West cannot easily avoid hard financial choices over the war

For more than two years, Ukraine has been defending itself against the onslaught of the Russian invasion. For just as long, the West has been implementing a series of actions in support of Kyiv: from economic and political sanctions against Moscow and a reduced dependence on Russian energy supplies, to direct military and financial aid for Ukraine and support for the country’s refugees.

Russian money in Western countries

The G7 countries have also backed the freezing of some 260 billion euros worth of Russian foreign exchange reserves. These funds are owned by Russia’s central bank and denominated in Western currencies. A key chunk of the total, some 190 billion euros, is denominated in the euro and currently deposited in the Euroclear settlement and deposit system in Belgium.

Unlike many other large countries in the world, Russia has a significantly smaller proportion of its reserves in United States dollars than it does in euros. This may partly have developed under an assumption that, in the event of any crisis, reserves in euros would be somehow safer and more inviolable for Moscow than dollar reserves, because European leaders would be less aggressive toward Russia than the Americans. It may also owe to reasons of prestige and status around the euro, and to practical circumstance, given that Europe has conventionally been the main customer of Russian energy, largely paying its bills in euros.

The Russian elite was surely aware of a basic truth in managing foreign exchange reserves: the reserve is effectively located outside its own territory. Its existence always implies a direct financial link to the country in whose currency the reserve is denominated. The golden rule of foreign exchange reserve management is thus to never have reserves in a country with which you intend to go to war.

A tempting magic wand for Western leaders

This is exactly where the story of frozen reserves gets interesting. As the Ukraine conflict drags on and turns into a war of attrition, conflict fatigue is setting in among Western allies, and the willingness to continue supporting Kyiv is diminishing in some corners. A war of attrition also wears down the will and resolve of Ukrainians themselves. Yet the defense of Ukraine needs this support no less urgently today than it did at the outbreak of the war.

That discrepancy between will and necessity has led some to seek creative ways of funding Ukraine’s war effort – such as turning the temporary freeze of Western-stored Russian assets into a full-scale, permanent seizure.

The political logic behind such a move is seductive; why shouldn’t the costs that Russia is exacting on Ukraine be recouped out of Russia’s very own resources? And why should the West have to borrow or pay anything out of its own tax revenue when there is such a big pot of Russian money available?

A decision that might raise legal and policy concerns if made within a single given country can be much easier to swallow when made on a pan-European level.

Not for the first time, the G7 countries flirted with this idea at the end of last year, but cautiously admitted that it was an interesting but legally complex course of action. Yet, to some extent, the idea has already been translated into actual policy. In February, the European Council effectively decided that the proceeds from the frozen Russian assets – though not the assets themselves – would be “separated” from the principal. These funds will become the basis for further financial assistance to Kyiv and for Ukraine’s future recovery and reconstruction. Surprisingly, this move has not caused much of a stir.

But it should. This was a significant, precedent-setting decision on the seizure of assets, even if only applied to accrued interest. Indeed, last year these revenues were just under 4.5 billion euros, and this year they will add up to around 3 billion euros. That is no small sum – roughly a year’s expenditure on the defense of this author’s home country.

The risky game of asset seizure

Even though in this decision the EU limited itself only to the revenues of frozen Russian assets, embracing the principle of asset seizure carries some risks. For one, there is the question of legitimacy. A pure confiscation of assets would certainly be acceptable, and even legally permissible, if Western countries were directly involved in a full-scale war against Russia. Similar confiscations took place during World War II, for example, on both sides. The West, however, is not at war with Russia; to the contrary, it seeks to avoid war, and for good reason. In that case, however, the confiscation of property becomes a legal problem under the rule of law – which does still govern Western states, even if Russia does not adhere to it.

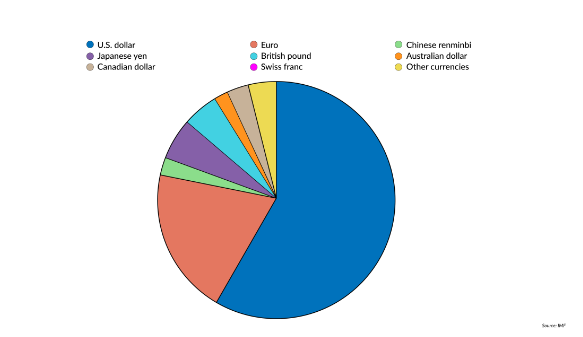

Looking at the global holdings of foreign exchange reserves shows the long-term dominance of Western currencies, chiefly the U.S. dollar. The share of world reserves for the euro is around 20 percent. The combined share of the “Anglo-Saxon” currencies – the U.S., Canadian and Australian dollars and the British pound – continue to account for more than two-thirds of all reserves worldwide, despite small fluctuations over time.

Yet these four countries are home to just under 6 percent of the global population. If we add the euro and the Japanese yen, we can say that combined, the currencies of economies home to less than an eighth of the world’s population account for well over 90 percent of global foreign exchange reserves.

Facts & figures

Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves, 2016-2024

Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves, end of 2023

One of the main reasons for this state of affairs is that these countries are based on the rule of law – on the enforceability of legal obligations and the predictability of legal systems. Political decisions to seize assets would be strongly incompatible with these principles; indeed, they fundamentally undermine them.

Moreover, confiscation would disproportionately affect the euro, because the dominant part of Russia’s reserves is euro-denominated. The risk of undermining the status of a safe reserve currency thus primarily concerns the single European currency. As an unintended consequence, this may further reinforce the reserve role of Anglo-Saxon currencies. One wonders whether this is what European leaders want.

For European integration realists – who, unlike the romantics, can sense the limits of how deeply the EU can feasibly integrate – the European Council’s reasoning presents further risks. It encourages the worst integrationist instincts in those who want to achieve their goals regardless of the necessary means. A decision that might raise legal and policy concerns if made within a single given country can be much easier to swallow when made on a pan-European level, overlooking domestic barriers.

The need for sustainable funding

The approach of seizing assets also reinforces the unfortunate political conviction that money can be found without having to persuade weary voters – without having to deal with the thorny issues of budget priorities, or having to choose between producing “more butter or more weapons.” Yet realistic prioritization must be the foundation for sustainable support for Ukraine. Once governments create the false impression that it is “no big deal” financially, because there is money floating around somewhere that can easily be summoned at no cost, they go down a seductive and dangerous path – one they may be tempted to follow again at any time in the future.

These dilemmas are particularly painful for those who are convinced of the justice of the Ukrainians’ struggle for their country and their people. Even (or especially) with these convictions, one should adhere to the basic principle valid in both medicine and economic policy: first, do no harm. In this case, the damage that asset seizure does to the rule of law in Western countries may be greater than any proceeds from the property seized.

When it comes to aid to Ukraine, the European Union can be remarkably hypocritical and paradoxical in its thinking. In virtually all EU countries, it is taken for granted that the most effective market-based aid – such as buying cheaper Ukrainian grain or other agricultural products – is unacceptable. After all, it would endanger European farmers. Although it might be easier to find political support for temporarily increasing subsidies to local farmers than for military and financial aid to Ukraine, it is hard to follow that logic, whether psychologically or politically. The desire to escape from this difficult political reality is what leads to policies like the seizing of Russian assets, which are certainly popular in the short term but risk doing more harm than good in the long term.

Scenarios

As the EU and other Western countries struggle to balance support for Ukraine with competing domestic political considerations, two scenarios present themselves with roughly equal, 50/50 likelihood.

Seizures of Russian assets

The first is that the West’s willingness to support the defense of Ukraine will gradually erode further as the war wears on. This will make financial and material resources increasingly difficult to find and the political will for direct support increasingly rare. There will be more interest in finding ways to circumvent this fading public support through seemingly risk-free financial engineering, such as the seizure of foreign exchange reserves. Similarly, there will be further interest in relying on additional, common EU debts so that they do not have to be dealt with by individual states and polities. This could threaten the credibility and financial position of the EU.

The policy fades away

The second scenario is that the pursuit of purportedly risk-free financial engineering will fade away. This could happen due to a stabilization of the conflict or the imposition of a ceasefire. Alternatively, support for Ukraine through more well-considered means may get a “second wind,” if the conflict evolves to pose a clearer and immediate existential threat to the West, or if Russian brutality raises a new wave of spontaneous support among European electorates.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/russian-asset-seizure/