To adopt or not to adopt? Pondering the euro question

Very similar beginnings but many different outcomes today – that is how one may sum up the history of monetary and exchange rate policy in the postcommunist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Yet the colorful history of the last 30-plus years of profound economic transformation, despite its long duration and rocky character, does not provide a clear answer to whether it is worth pursuing a fully independent monetary policy at the national level in the context of an integrating Europe, or better to merge the national currency with its nearest monetary hegemon as quickly as possible – in this case, join the euro area.

The 30-plus years of “laboratory experiments” in Central and Eastern Europe with various exchange rate and monetary regimes have provided both rival camps with good arguments. The debate on the wisdom of embracing the European Union’s common currency remains open. So let us revisit this history in more detail.

Every country is a separate story

The former Soviet bloc countries in Europe had a common denominator after the bloc’s disintegration (1989-1992): they were all looking for a fundamental macroeconomic anchor, a fixed point in the period of transition to a market economy with free pricing, liberalized foreign trade and private ownership. That anchor was most often, usually at the advice of international monetary institutions, a fixed exchange rate – a system in which the value of one currency is tied to another.

While former East Germany avoided inflation and instability, the strong exchange rate drove much of its industry and labor force west.

Rates were most often fixed to the German mark – the monetary hegemon of Western Europe – or the United States dollar. Alternatively, it could be a basket of hard currencies containing the British pound, the Japanese yen and the Swiss franc, along with the abovementioned currencies. The Baltics, Bulgaria, Hungary and Poland chose this route. Before they could start, though, they had to devalue their artificial communist-era exchange rates, which did not correspond to reality.

Within a few years, however, the countries’ paths began to diverge. Former East Germany merged with West Germany, adopting the latter’s deutsch mark at a one-to-one ratio. The idea was to unite the economically disparate parts of the country through a hard currency union like Italy had done in the 19th century. While former East Germany avoided inflation and instability, the arbitrarily strong exchange rate drove much of its industry and labor force west, necessitating mammoth fiscal transfers that continue to this day.

Reluctance to go it alone

Several countries stuck to a fixed exchange rate in the form of a currency board: an extreme form of the pegged exchange rate in which a country’s money stock can be no larger than its forex reserves.

That means an absence of autonomous monetary policy and reluctance to pursue it. Such was the case of Estonia and Lithuania and partly also Latvia. These countries took a fixed currency peg to the West as an economic and geopolitical insurance policy against their giant eastern neighbor. Bulgaria, too, embraced the strict currency board regime in 1997 after the chaos and hyperinflation of the 1990s and has succeeded in remaining in it to this day.

The only country that rushed into the eurozone just before the crisis was Slovenia in 2007. It, too, had a managed floating exchange rate. By quickly adopting the euro, Slovenia also wanted to show that it did not belong to the chaotic Western Balkans. It was followed two years later, in 2009, by Slovakia, which, after the breakup of Czechoslovakia in 1993, had remained the smaller and poorer part of the former federation and struggled with the distrust of international markets during the authoritarian governments of Prime Minister Vladimir Meciar (1990-1991; 1992-1994; 1994-1998). The Slovak koruna was unstable. Replacing it with the euro was seen as the completion of the radical economic reforms introduced after the democratic overthrow of the Meciar regime.

Two Western Balkan countries, Montenegro and Kosovo, use the euro as their currency unilaterally, without the European Central Bank’s (ECB) direct permission, as they are not EU member states. The two states desired political and economic emancipation from Serbia, which, after 1989, had experienced a dreadful episode of hyperinflation.

The existing eurozone member states do not want Bulgaria among them.

Croatia, Serbia’s archenemy in the Balkan wars of the 1990s, was also in a hurry to join the eurozone following its accession to the EU in 2013. The degree of euroization of its economy was so high that any independent monetary policy would be just an illusion. And as of January 1, 2023, Croatia adopted the euro and became the 20th member of Europe’s single currency club.

Demonstrably, each of the post-communist euro area member states had its own accession story and its reasons for joining – historical, romantic and geopolitical instead of purely economic. A particular category is Bulgaria. Despite its exemplary compliance with the Maastricht criteria, for long it was not even allowed to enter the ERM II exchange rate mechanism, the antechamber to the euro area. It still does not have the euro, even though it began its journey toward it simultaneously with Croatia. Why? The existing eurozone member states do not want Bulgaria among them.

From a fixed exchange rate to other systems

More interesting exchange rate and monetary developments occurred in the countries that are in the EU but have not introduced the euro and are not planning to do so. The EU countries that have not negotiated a currency opt-out are Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Sweden; Denmark has an opt-out.

The Swedes voted in a 2003 nonbinding referendum not to join the eurozone and the country is not under pressure to do so today, even though it remains formally obliged under the treaties to seek membership. Sweden is, however, a global benchmark of independent, self-sufficient monetary policy. It is one of the pioneers of inflation targeting and has a freely floating exchange rate. The world has been learning from its central bank. The post-communist EU countries are looking up to the Riksbank too.

Denmark, in turn, represents a paradox in this respect. It has an opt-out clause from the euro, yet it has had a strict fixed exchange rate to the euro and conducts no monetary policy of its own, only issuing its banknotes and coins.

Denmark had followed a fixed exchange rate policy since 1982, when, for macroeconomic stability, it introduced a peg to the German mark. In 1999, it merely switched to a peg to the euro, thus replacing its subjection to one institution in Frankfurt, the Bundesbank, with another in the same city, the ECB. In its reluctance to make monetary decisions, Denmark is historically reminiscent of Austria with its historical fixed link to the German mark and its perceived need to be in the euro area as soon as possible.

Poland and Hungary tried this strategy for years, only to find that it sustains high inflation and embeds it in wage and price contracts.

In contrast, the countries of Central Europe have been groping for approaches through turbulent times. After short periods of experimentation with fixed rates, Poland and Hungary moved to a crawling peg system in which a fixed-exchange-rate currency can fluctuate within a bracketed range. Under such a managed devaluation design, the region’s reforming economies could seek to stabilize their local currencies’ exchange rates against the hard currencies in a high-inflation environment.

Macroeconomics teaches us that if one country (say, Poland) has a higher inflation rate than another (say, Germany) and has a fixed exchange rate with it, the former will gradually lose price competitiveness against the latter. That leads to a currency crisis and the need for an abrupt exchange rate adjustment. Managed devaluation is intended to prevent such disruptions.

Poland and Hungary tried this strategy for years, only to find that it merely sustains high inflation and embeds it in wage and price contracts. Both countries eventually took the sensible course of trying to float freely and stabilize domestic inflation on their own.

Three countries’ case

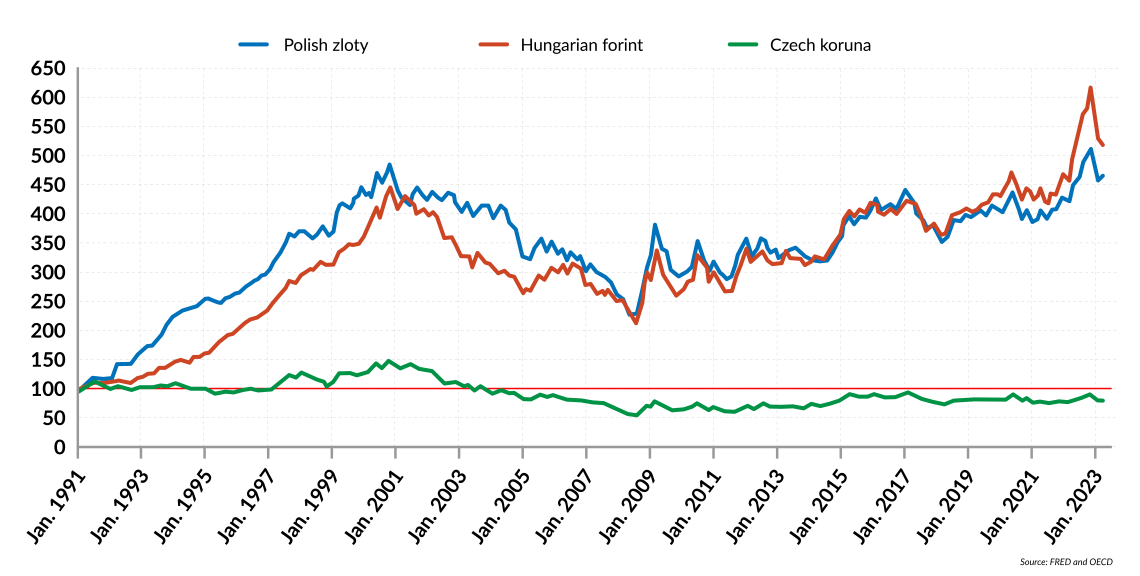

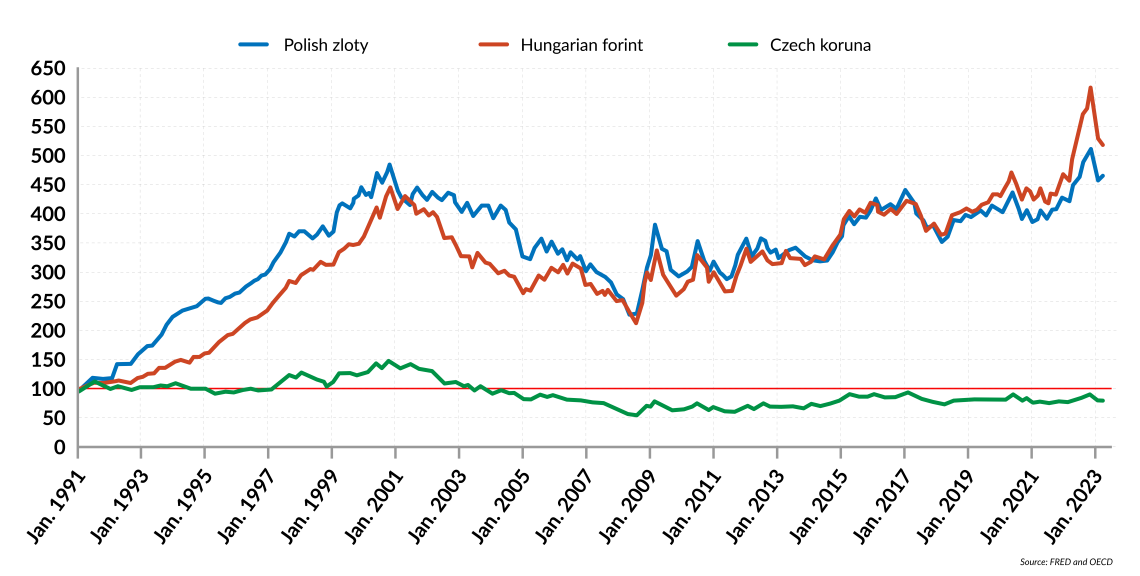

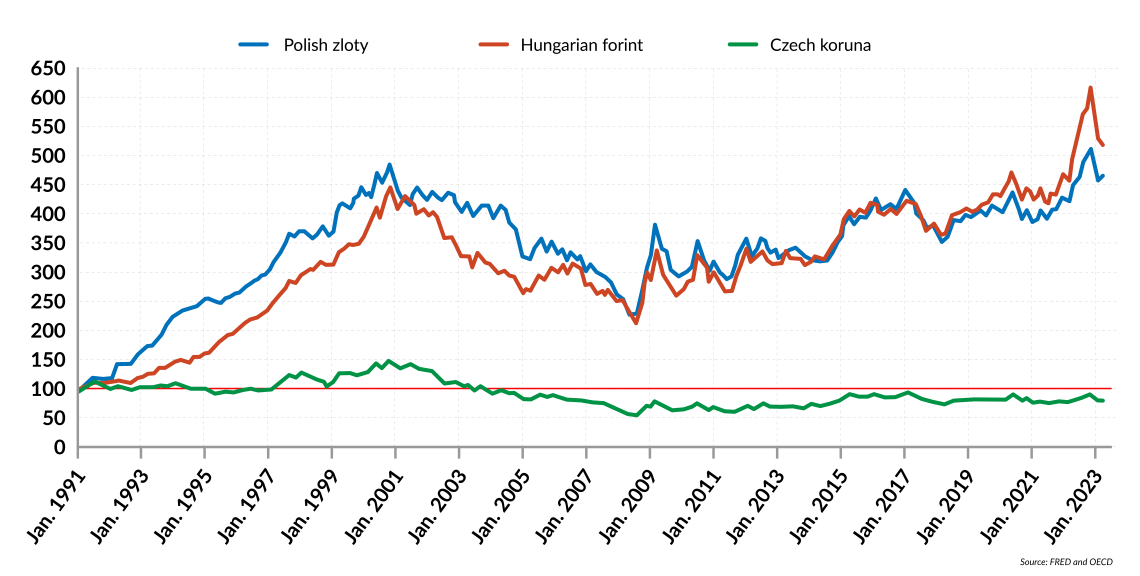

Facts & figures: different currency exchange rate outcomes

This approach, called inflation targeting, has been applied by Poland since 1999 and by Hungary since 2001, although each with a different ability to achieve low and stable inflation (Hungary is systemically weaker in this regard and used to being viewed as a high-inflation, high-debt country).

However, the pioneer in autonomous monetary policy is the Czech Republic, another country that does not use the euro as its currency and where support for it is relatively low. It did not undergo a switch from a fixed rate to a crawling peg, and its exchange rate regime ended, textbook-style, in a currency crisis and a significant debasement during the Asian turmoil in early 1997. However, the Czech economy did not suffer from such high inflation in the 1990s as Poland and Hungary, so its return to equilibrium did not take as long.

Following that experience, the Czech central bank abolished the fixed rate, introduced a float and adopted inflation targeting. Because the setup was successful for many years, with inflation low and the national currency appreciating, there was no grassroots demand to adopt the euro. That contrasts with Poland and Hungary, where higher inflation and higher nominal interest rates led to growing interest in loans denominated in lower-interest currencies such as the euro and Swiss franc. That ended in disaster in 2008. During the financial crisis, the depreciation of the zloty and forint ballooned the debt of Polish and Hungarian households: they suddenly had to outlay more in zlotys and forints for their loan installments set in in euros and francs.

Hard awakening in 2008

To sum up, it is hardly surprising that the countries with autonomous monetary policies within the EU show a limited desire to enter the eurozone. That group ranges from the strongly eurosceptic Swedes and Czechs to the more Europhile Hungarians (who apparently also see the euro as insurance against their irresponsible homegrown politicians).

However, under Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Hungary amended its constitution, which now says that the forint is the country’s currency. The fundamental law must be amended again if the euro is to be adopted.

The discourse on joining the euro club has been altered by the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent Great Recession. The crunch revealed that the eurozone was not necessarily a group of better and more stable economies. It broke its rules and was more indebted than those that stayed out. At the end of Q3 2022, the average debt of the euro area countries was 93 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), as against only 85 percent for the EU as a whole. Yet the criterion on sound public finances in the EU’s core treaties remains the well-known, legislatively enshrined 60 percent.

Lessons from monetary history

All this historical context offers good insight into the debate on autonomous vs. completely nonautonomous monetary policy. First, there is no universal model. Second, factors other than purely economic or monetary ones inform the choices of monetary regimes.

Third, there is no clear answer to whether autonomous monetary policy is better than a fixed exchange rate or monetary union membership. It depends on how well or poorly other parts of the system work in a country.

If economic policies fail in a country, not even the euro can save it from trouble (like in Greece). If everything works satisfactorily, the euro is unnecessary (like in Sweden). Monetary policy is only one adjustment mechanism. If it does not function, other mechanisms – a flexible labor market, fiscal policy – must assume its role. If they are not available, changes in the economic environment will hurt, as monetary policy cannot soften shocks and smooth things out.

The choice of monetary policy can affect the pace or level of growth, but it cannot set a country’s direction.

Fourth, the 1990s economic miracle in the postcommunist world happened regardless of the countries’ particular monetary policy choices. Aside from large parts of the former Soviet Union and the war-ravaged Western Balkans, the remaining former Soviet bloc states have experienced explosive wealth increases roughly three to seven times over the last 30 years. The choice of monetary policy can affect the pace or level of growth, but it cannot set a country’s direction, which is determined by its core economic policy.

Fifth, if a country is satisfied with a given monetary regime, do not expect it to change things. According to the old American wisdom, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

The question of whether to adopt the euro does gain, at times, some traction in public debate. However, it is not a substitute for resolving the fundamental issues of optimal domestic policies to increase the general welfare and ensure economic and political stability.

Scenarios

Two scenarios emerge. The first assumes that the geopolitical effects of the world breaking into competing blocks (and, in the EU’s case, its centralization tendencies) will be accompanied by persistent inflation and governments’ fear of having to bear the costs of fighting it on the national level. The desire to spread these costs across borders to a larger community will lead most of today’s non-euro EU member states to adopt the common currency within five years. This author sees the probability of this scenario materializing at about 40 percent.

The second scenario assumes that the upswing in inflation will not persist and that the war in Ukraine, with its pressures on energy, food, currency and other markets, ends before long. The desire to retain the monetary policy autonomy and not “give in” to collective decision-making will trump the centralistic, political pressures to expand the euro area further. The probability of this scenario is 60 percent.

The original report was published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/euro/