Sanctions and the geopolitics of trade

The prominence of free trade as a guiding principle in shaping relationships between countries has steadily diminished since the end of the Cold War. Instead, geopolitics has begun to regain its influence. This shift has major implications for global economies and consumers as nations impose trade restrictions such as unilateral sanctions and export controls. Accordingly, the changing international trade landscape is reconfiguring global markets as economies adapt to new trade barriers and alliances.

Over the past decade, trade restrictions driven by geopolitical factors have significantly increased. A recent report from the World Trade Organization regarding the G20’s largest economies highlighted that from October 2023 to October 2024, new export restrictions affected an estimated $230 billion in merchandise exports, a sharp increase from about $121 billion the previous year.

As geopolitical rivalries evolve, new sanctions, countersanctions and other restrictive measures are expected to influence trade flows through 2025 and beyond. It has become increasingly clear that rapidly changing geopolitical dynamics could lead to unilateral trade restrictions being lifted at any moment, especially concerning the United States’ sanctions on Russia. This situation follows a joint statement issued by Washington and Moscow after their recent summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where both parties emphasized the importance of “future cooperation for mutual geopolitical interests” and highlighted “historic economic and investment opportunities.”

Seismic new shifts in global trade flows

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, global trade flows between Moscow and Western countries saw a dramatic decline. Exports from the U.S., the European Union and the United Kingdom to Russia plummeted sharply due to the imposition of economic sanctions. Between the first quarter of 2022 and the third quarter of 2024, the EU experienced a 58 percent drop in exports to Russia, while imports from Russia fell by 86 percent. The decline was even steeper for sanctioned goods, with two-way trade flows decreasing by 80 percent compared to other products. The decrease in bilateral trade between Russia and the U.S., and Russia and the UK, was even more pronounced: The UK’s imports from Russia nosedived by 94 percent, while its exports to Russia fell by 74 percent.

After several rounds of Western sanctions, Russia has shifted its trade relationships, boosting commerce with developing nations. Notably, trade flows between Russia and China jumped by 175 percent, increasing from $140 billion in 2021 – just before Moscow invaded Ukraine – to an all-time high of $245 billion in 2024.

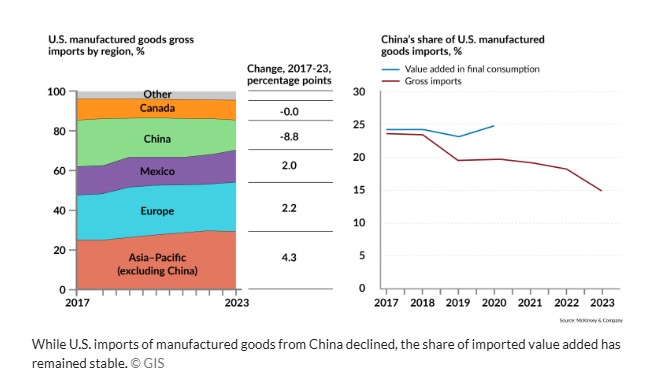

Facts & figures: The U.S. has diversified its import share away from China

The growth of trade between Russia and India has been even more substantial. According to India’s financial year data (April to March), their bilateral trade skyrocketed by 500 percent, increasing from $13 billion in 2021-2022 to over $65 billion in 2023-2024. In the current fiscal year, trade levels are expected to increase even further.

Russia’s direct trade with other Asian and Middle Eastern economies has also sharply increased, particularly with Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong. Key developing economies in the Western Hemisphere, especially Brazil, have also ramped up their business dealings with Russia. By 2024, their bilateral trade reached $12 billion, increasing from $7.5 billion in 2021.

Emerging new trade routes

As sanctions have driven Russia to pivot trade away from Europe mainly toward Asia, new intercontinental supply chains have emerged across the Eurasian landmass. A notable logistics network is the 7,200 kilometer-long International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). Initially developed in 1999 by Russia, Iran and India, this route links St. Petersburg in Russia to Mumbai, India’s financial hub, at its southern end. It passes through Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, and the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas, creating a critical connection between these nations. The route mainly focuses on transporting freight by ship, rail and road.

Western sanctions against Iran hindered progress on the project in the mid-2000s. However, following the imposition of sanctions on Russia in 2022, the INSTC regained momentum. Countries such as Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Oman, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have also started collaborating on this trade route, further enhancing its development.

Sanctions circumvention boosts unexpected trade flows

Exports from the EU and the UK to several of Russia’s neighboring countries, including Armenia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan – all members of the Russian-led Eurasian Customs Union – have increased by a third since 2022. In turn, these countries’ exports to Russia have risen by similar levels.

The emergence of new trade routes is closely connected with efforts to circumvent trade restrictions on Russia. This trend is particularly noticeable in specific product categories, where items are either partially sanctioned or closely resemble those sanctioned. These include dual-use goods, metals, minerals, technologies and equipment used in oil and gas extraction.

While trade through Russia’s neighboring former Soviet-bloc countries can be used to bypass economic sanctions, such intermediated trade can only operate on a limited scale. Nevertheless, this approach complements broader patterns of trade diversion with key partners, particularly China and Turkey.

After a brief decline in 2022, Chinese exports to Russia have increased, covering a variety of products, including vehicles, machinery, electronics, metals, plastics and rubber. Notably, Russia’s demand for military-sensitive integrated circuits has soared. The influx from China has effectively replenished Russia’s electronics markets and partially addressed its technological needs. Additionally, Chinese automobiles, trucks and components have nearly dominated the Russian vehicle market, enabling China to emerge as the world’s leading car exporter in 2023.

Turkey exported goods worth $10.9 billion to Russia in 2023 while importing significantly more, totaling $45.6 billion. A similar trend can be seen in their investment relationships. Russian investments in Turkey focus on strategic and high-value sectors, including energy, metallurgy, banking and automotive industries. In contrast, Turkish investments in Russia are primarily directed toward construction, alcoholic beverages and chemicals.

Will more extraterritorial sanctions reverse new trade flows?

Since 2022, Russia has continued generating substantial oil export revenues, averaging around $665 million per day. This figure has remained steady over the past two years despite the changes in trade routes caused by sanctions.

To disrupt these new trade patterns, former President Joe Biden introduced a comprehensive sanctions package in January 2025, targeting Russia’s logistics networks with secondary sanctions. These sanctions specifically affect third-party operators such as oil and gas traders, oilfield service providers and ports interacting with Russia’s state-owned container ships. Notably, 183 vessels, referred to as Russia’s “shadow fleet,” transport oil and liquefied natural gas by sea.

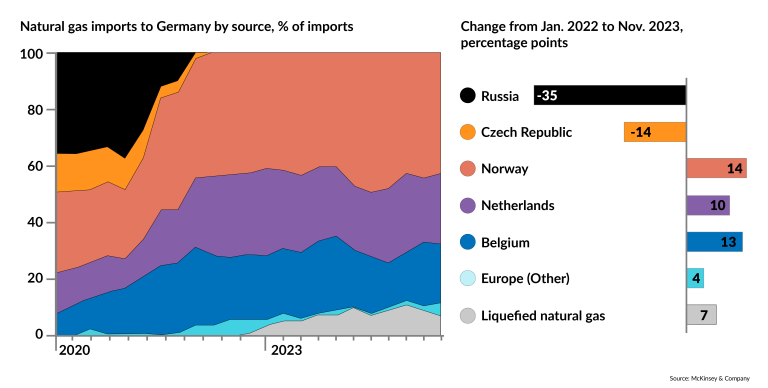

Facts & figures: Germany’s exports have shifted away from Russia

The preemptive ban imposed by China’s Shandong Port Group on dealings with Russian oil tankers, along with similar announcements from private Indian port operators and oil traders, highlights the seriousness with which these sanctions are being regarded.

Despite President Biden’s late efforts, the situation may not significantly change. In 2024, the U.S. enacted the Stop Harboring Iranian Petroleum Act, imposing sanctions on foreign entities involved with Iranian oil. Although these regulations affected many Iranian vessels, including 20 percent of liquified petroleum gas tankers, Iran’s liquified petroleum gas (LPG) exports hit a record high last year, mainly to China and India.

The extent to which President Trump will enforce, adopt or revoke sanctions against Russia, Iran and other countries remains uncertain. He has suggested imposing additional sanctions on Russian exports to the U.S. if Moscow does not engage in meaningful peace negotiations over Ukraine. However, the White House has now indicated that sanctions could be revoked as both the U.S. and Russia move toward normalizing their relations.

Scenarios

Highly likely: The West’s international trade flows will increasingly reconfigure into its geopolitical bloc

There is a growing possibility that global trade may fragment into rival blocs of nations, forming geopolitically aligned partnerships. These could be broadly classified into three groupings: Western nations, Eastern nations and the mid-aligned states of the Global Majority (sometimes referred to as the Global South). This is notwithstanding the unpredictable nature of Mr. Trump’s transactional foreign policy which may exacerbate or even contradict these alignments

More inward looking Western bloc trading flows may result, especially from increasing geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China in the future, extending the decline in their bilateral trade flows over the past few years. For example, the U.S. has moved its import sources away from China across various manufacturing sectors, increasing its reliance on other Asian economies, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Between 2017 and 2023, China’s share of U.S. manufactured goods imports declined from 24 percent to 15 percent. Notably, China’s electronics sector saw the steepest decline, falling from 50 percent to 30 percent in its U.S. import share.

While some of these changes can be attributed to the impact of rising tariffs on imports from China, that is not the whole story. Although laptops and cell phones are not subject to these tariffs, China’s share of U.S. imports for these products still declined in 2022 and 2023. Corporate entities, notably technology companies, from North America and Europe are increasingly moving production and sourcing operations out of China to alternate locations in the so-called “ABC,” or “anything but China” approach. This builds on de-risking strategies developed after Covid-19 trade disruptions left global markets without specific products made almost exclusively in China.

Additionally, countries worldwide are increasingly wary of China’s export practices as Beijing seeks to boost exports to offset its cooling domestic economy. Many nations, even those close to China, are establishing barriers to prevent Chinese dumping.

Some Western nations are finding that trade relations between rising geopolitical rivals can also be a potential source of economic vulnerability. A clear example is the significant disruption of Australia’s coal, wine and barley exports to China since 2021, following Beijing establishing barriers to some goods and services from Australia.

Conversely, geopolitical hostility has affected several Western nations’ imports of key resources. Germany, in particular, faced a major challenge in recent years due to its heavy reliance on Russian energy exports. Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine led to a complicated and swift reconfiguration of Germany’s international trade routes. Berlin’s reliance on Russian natural gas has since plummeted, from around 35 percent of its energy imports in January 2022 to less than 1 percent in 2023.

As a result, Germany has turned to alternative sources, increasing its gas imports from Norway and bolstering these supplies with liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the U.S. Germany’s manufactured exports have also dramatically shifted away from Russia, with increased shares going to the U.S. and nearby developing European economies.

It remains possible that a potential trade war with the U.S. could markedly disrupt closer trading arrangements between Western-aligned nations.

Also very likely: Trade flows from Western and Eastern blocs will reconfigure toward Global Majority economies

The growing influence of the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) coalition – especially with the addition of new member states such as Indonesia, the UAE, Egypt and others – presents a counterweight to Western trade and regulatory dominance of the global trading system. During the 2024 BRICS summit, member nations proposed an alternative global payment system to diminish their reliance on the U.S. dollar. If successful, this could pave the way for parallel trade networks that challenge the long-standing dominance of the G7 advanced economies and call into question the effectiveness of their unilateral sanctions.

Moreover, as geopolitical rivalry between the U.S. and China escalates, mid-aligned Global Majority economies have stepped in to fill the resulting trade vacuum. For example, Mexico has increased its share of U.S. imports, surpassing China and becoming the U.S.’s largest trade partner. This shift exemplifies the concept of nearshoring, where a company relocates its operations to a nearby country, often with a shared border. Even so, President Trump has significantly complicated the emerging role of nearshoring, as Mexico and Canada have been threatened by substantial U.S. tariffs on all imports, in addition to sizeable tariffs on specific industries.

Southeast Asia has also captured a portion of China’s exports that would have previously gone to the U.S., reflecting the idea of friendshoring – the formation of supply chain networks that prioritize countries viewed as political and economic allies.

The economies of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), along with Brazil and India, are increasingly engaging in broader trade across the geopolitical landscape. Vietnam, recognized as a high-growth economy with a mid-aligned status, has not only boosted its exports to the U.S., but is simultaneously strengthening its trade and investment ties with China and Europe. For example, in January, Vietnam and the Czech Republic upgraded their relations to a Strategic Partnership to bolster mutual trade and investment.

For some observers, the U.S. transition to importing goods from Vietnam is seen as simply redirecting trade from China, offering little added value from Vietnam itself. China and the U.S. remain intricately linked through supply chains that have simply grown longer and more complex.

In 2023, while Mexico became the largest import partner for the U.S., particularly in the transportation equipment sector, a significant share of the component parts still came from China. More controversially, Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers are expanding their presence in Mexico, positioning the country as an export hub for the U.S. This strategy allows them to bypass existing U.S. tariff barriers on China. In turn, one reason behind the Trump administration’s threats to impose high tariffs on Mexico is to curb China’s growing corporate influence and trade connections with the country.

Like the U.S., China has been redirecting its trade focus toward mid-aligned Global Majority states. Between 2017 and 2023, as China experienced a decline in its export share to the U.S., this was balanced out by increased exports to ASEAN economies. This economic bloc has become China’s largest bilateral trade partner in recent years, surpassing the EU.

China has also increased its imports from ASEAN countries, the Middle East and Latin America. At the same time, it has scaled back imports from U.S.-aligned nations, including its traditionally larger trade partners such as the EU, Japan and South Korea. Due to these reconfigured trade flows, developing economies, including those from geopolitically aligned Eastern and mid-aligned Global Majority groupings, accounted for over 50 percent of China’s goods trade in 2023, up from 42 percent in 2017.

Another example of an Eastern bloc state trading more with a Global Majority counterpart has been Russia’s burgeoning trade with India, especially in the energy sector. The share of India’s energy imports from Russia jumped from just 2 percent in 2017 to over 25 percent by 2023. Correspondingly, India has boosted its exports of refined petroleum products blended with Russian crude oil. These flows have primarily targeted markets in the U.S. and the EU while carefully navigating potential sanctions.

As geopolitical tensions rise, trade flows are expected to be further reconfigured. This economic shift will likely benefit economies in the Global Majority as productive capacities move away from the competing Western and Eastern blocs into these more aligned intermediary jurisdictions. However, President Trump’s fast-unfolding and unpredictable transactional approach to international relations and willingness to unleash tariffs on friend and foe alike will likely complicate trends in these recently emerging trade flows. Accordingly, tariffs may overtake sanctions in becoming key drivers of geopolitical and geoeconomic forces going forward.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/sanctions-trade-routes/