Peso appreciation in Argentina

The issue of peso appreciation in Argentina has been a growing concern since the beginning of the new government. The current monetary policy has chosen a monthly depreciation of 2% of the exchange rate in the face of inflation that has not yet converged to those levels. From the beginning, this spread has raised doubts about the sustainability of the exchange rate regime. A year later, concerns about the exchange rate delay have been increasing. In fact, this problem was already mentioned in the IMF’s June report of this year.

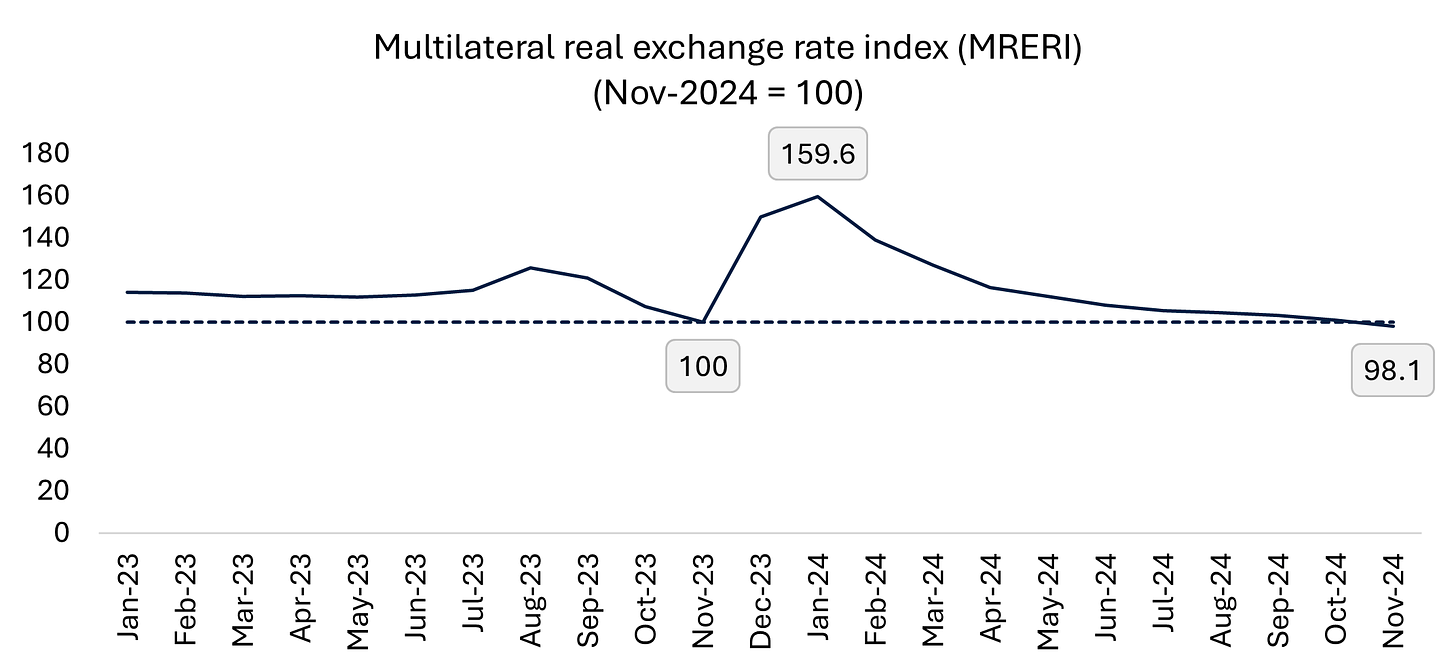

Let’s first look at the arguments that support a concern regarding the exchange rate delay. When taking office in December, the government devalues (rounding) the exchange rate from 365 to 800 pesos per dollar. From January to November, accumulated inflation was 112%, while the accumulated depreciation of the peso was “only” 20%. In terms of the multilateral real exchange rate index (MRERI), everything gained from December’s devaluation has already been lost. In fact, according to the MRERI, the peso is more appreciated than in December 2023.

As Emilio Ocampo explains in his last post, in the case of Argentina a (long) time series is not a good proxy for estimating the equilibrium real exchange rate (ER). Since variables tend to revert to their equilibrium values, a long enough time series can indicate where the equilibrium TCR would be located. This method assumes that the fundamentals and structure of the economy are constant, i.e., the equilibrium point is always the same. This is exactly the opposite of what is presented in the case of Argentina, with multiple exchange rate regimes, monetary policies, political instability, and exchange controls to mention just a few examples.

Perhaps ironically, this does not mean that a shorter time series is not useful. For example, if at a given time it is “clear” that the peso is appreciating, and after a strong devaluation the RER quickly returns to its initial values given an exchange rate control regime, the peso has likely appreciated again. This is precisely what happened in 2024. If the RER was appreciated in December 2023, why wouldn’t it be today?

There are three arguments why the crawling peg of 2% would not be problematic. The first is that inflation converges to 2% per month, at which point the nominal exchange rate and inflation will move at the same pace. The second is that given the reforms carried out by the government, there is a new equilibrium exchange rate and therefore it is not necessary to modify the nominal exchange rate. The new balance TCR means a more appreciated weight. The third is that the BCRA (the Argentine central bank) is buying reserves. It seems to me that the three arguments are problematic, or at least not enough to maintain that there is currently no exchange rate delay.

The first, clearly, is not an equilibrium condition. If at the time that inflation and the exchange rate converge at the same rate there is the peso is appreciated, then the appreciation remains “constant.” Therefore, if there is a problem of an appreciated peso, the convergence of the inflation rate to the crawling peg does not make the disequilibrium disappear nor does it imply that it can be exited without any problems. The government’s idea of reducing the crawling peg to 1% once this convergence occurs suggests a new round of peso appreciation and reveals that the government sees the exchange rate as a tool to control inflation.

The second argument has a problem of magnitude and timing. It is not obvious that the reforms seen so far can explain such a strong shift in the RER. The government has indeed made progress on many deregulations, especially from Sturzenegger’s office. The fact that these deregulations are necessary does not mean that they are sufficient to explain the necessary shift of the new RER. An economy suffocated with taxes and corseted with strict capital controls cannot grow in a sustained way no matter how many regulations are eliminated (it can rebound after a tremendous collapse of economic activity). This is the problem of magnitude in the second argument. In the 1990s, the Menem government carried out several privatizations, implemented an exchange rate regime that was considered credible, and opened up the economy. So far, the government has increased taxes, has not privatized any state-owned company, and the economy remains under strict capital controls. There is still a long way to go to argue that the reforms made so far are of great magnitude. It is important not to confuse taking the first steps in the right direction with having reached your destination.

The timing problem has to do with the time it takes for a change in productivity to materialize so that it can explain a new equilibrium RER. Investments must come in large proportions and be completed, which takes time. The current human capital is similar to that of 2023. The fact that government policies indeed to another equilibrium RER does not mean that the new equilibrium value is the current one. Added to this, timing is another problem. The equilibrium RER does not depend only on the productivity of the economy, it depends on the expected productivity. The probability that the reforms that are being seen will last in the medium and long term is very low, given that the probability of a left-wing populist being elected again is very high. While the laws in Argentina do not guarantee stability, the fact that the current reforms are implemented via decree does not contribute to that credibility.

The third argument refers to the expected behavior of reserves when the peso is appreciated (a cheap dollar). With a demand for dollars greater than the supply, it is to be expected that the BCRA will lose reserves when selling them in the market. The argument itself is curious, given that the BCRA accumulated reserves at the same time that the peso appreciated under the Martínez de Hoz’ “Tablita”. Today there is an energy surplus that helps finance the increase in the demand for dollars for tourism and cards. In other words, it helps to sustain a lagging exchange rate. There are two other reasons to take into account. One is the remarkable success of the tax amnesty, which implied an inflow of dollars as gross reserves of the BCRA. The other is the influence generated by the carry trade. In other words, ceteris paribus, with an appreciated exchange rate, the BCRA loses reserves. However, the ceteris paribus condition is not met, where the tax amnesty and attractiveness of the carry trade help to offset the impact of the backward exchange rate on reserves.

Every time Argentina tried to control inflation by delaying the exchange rate, it ended up in a crisis. Milei supporters should be careful not to get too excited too early and fall into the “this time is different” syndrome. How to get out of this imbroglio, in a country where the regulated exchange rate ends in crisis and a flexible exchange rate regime is unstable? One option is to achieve a genuine increase in the demand for pesos. I am referring to an increase in the demand to hoard pesos for the pesos themselves, not a demand for pesos to obtain profits in dollars (carry trade). Is this change in peso sentiment doable in Argentina? Another option is to implement a formal de jure dollarization of the economy. By dollarizing financial assets, the problem of “stock” (overhang) is eliminated. According to the government, the “stock” problem prevents them from getting out of the clamps. Counterintuitively, dollarization requires fewer dollars than eliminating the exchange rate clamp.

The concern about the exchange rate delay is reasonable. A forced and disorderly exit from the crawling peg may have an impact on the midterm elections, seriously affecting the political power the government needs to move forward with the reforms that are still needed. The government may run the risk of becoming a lame duck in the middle of the presidency if an exchange rate delay unleashes a political cost before the elections. The other option is to maintain capital controls until after next year elections.

This material was originally published here: https://economicorder.substack.com/