Broken money – and how to fix it.

Minutes of the Advisory Board meeting

Key Take Aways:

- Lyn’s new book, “Broken Money”, explores the past, present, and future of money through a technological Emphasizing the impact of inventions like the telegraph on monetary history, the book delves into the evolving nature of currency, from credit theories to contemporary innovations like Bitcoin, stable coins, and the potential for global competition in the monetary landscape.

- The interconnectedness facilitated by these technologies challenges the traditional silos of fiat currencies, allowing for global transactions and reshaping the future of money.

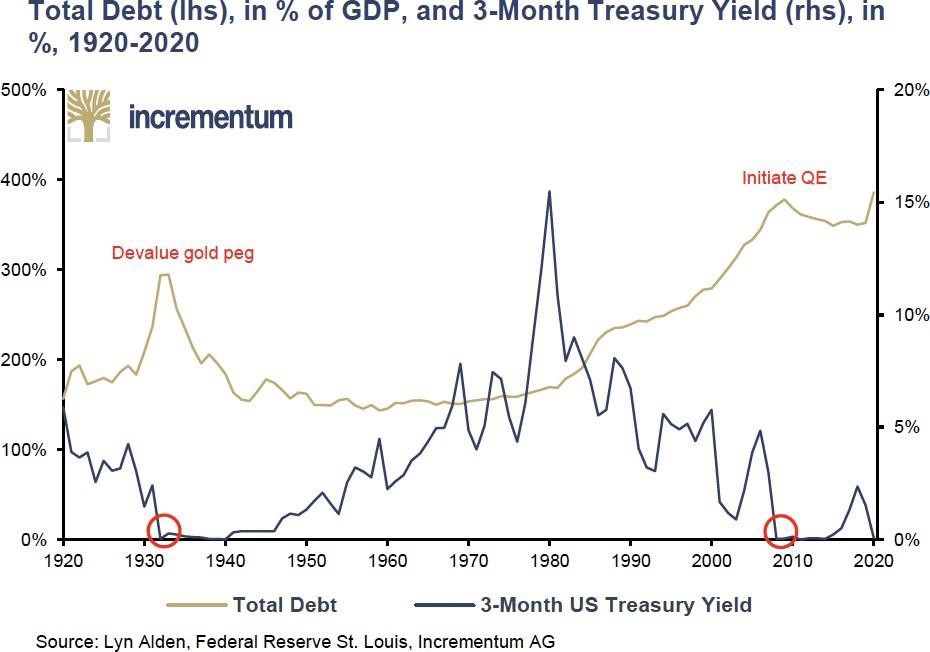

- The long-term debt cycle indicates a shift from a disinflationary private sector debt bubble to an inflationary.

- The Western world is burdened by sovereign debt and faces a fiscal challenge which is likely to be resolved through inflation of the money supply.

- Interest rate-sensitive industries are struggling while loose fiscal policies benefit those on the right side of large deficits. This creates a stark contrast in industry performance.

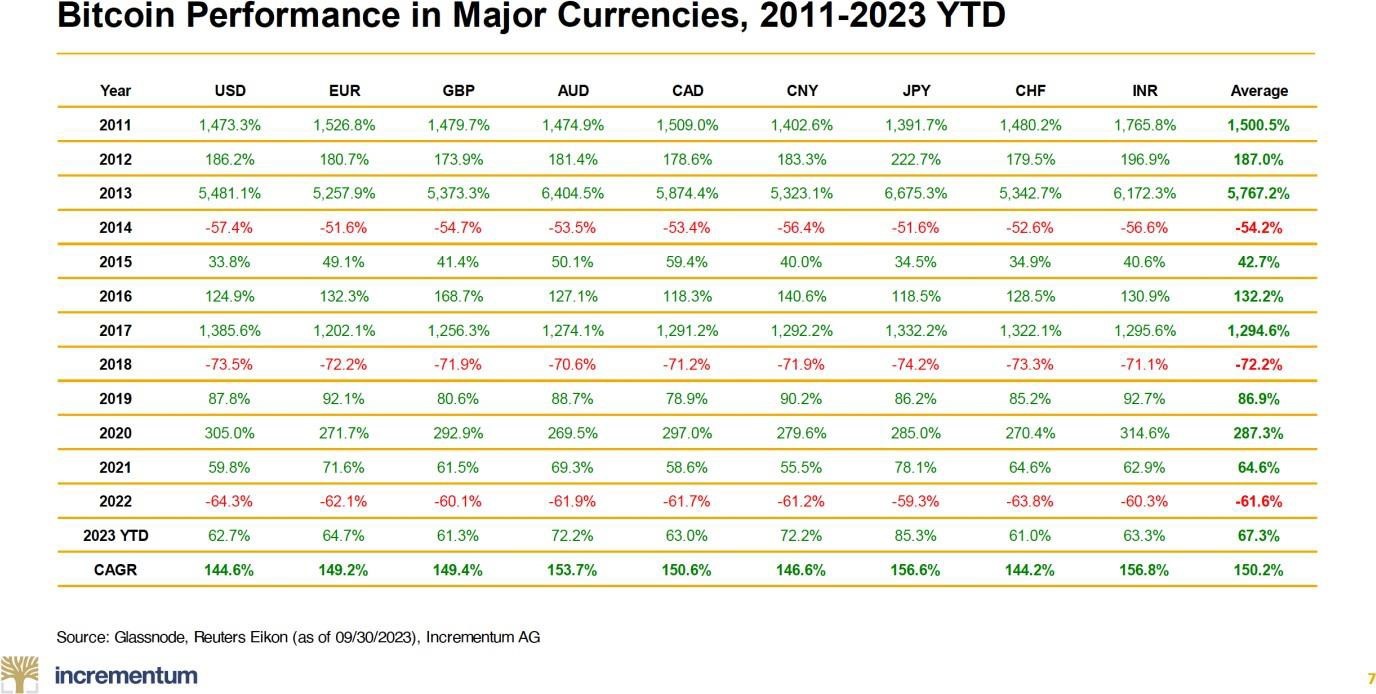

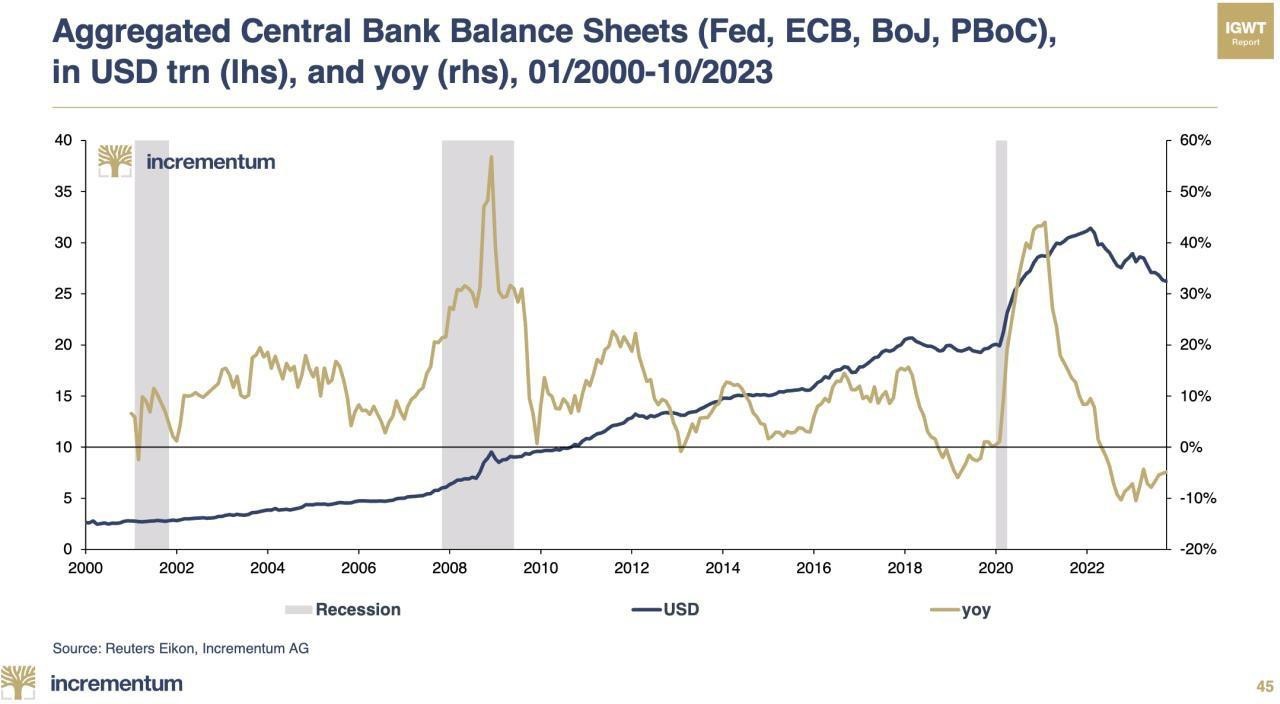

- Gold and especially Bitcoin’s performance is highly correlated to the expansion of money Your expectations of performance for these assets should reflect your views on monetary inflation.

Biography of our special guest: Lyn Alden

Lyn Alden is a widely followed macroeconomic analyst that provides research for retail and institutional investors. Her focus is on the analysis of monetary systems and energy markets.

In addition to her research publications, Lyn also serves on the board of directors for Swan.com and is an advisor to the venture cap- ital firm Ego Death Capital. In these roles, she works with investors and startup founders to help build the next generation of monetary technologies and financial services. Prior to her current work, Lyn spent over a decade in the aviation industry in a variety of engineering, procurement, and managerial roles.

Lyn’s background consists of a blend of engineering and finance. She holds a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a master’s degree in engineering management, with a focus on systems engineering, engineering economics, and financial modeling.

Ronnie Stoeferle: Ladies and gentlemen, it’s a great pleasure having you here for our Q4 2023 Advisory Board Meet- ing and it’s an even greater pleasure to have Lyn Alden here for the second time. Lyn, thanks for taking the time.

Lyn Alden: Thanks for having me back, happy to be here.

Ronnie Stoeferle: Today is Monday, the fourth of December, gold has actually made a pretty significant all-time high, it traded above $2170 in the early hours, but then made a pretty interesting reversal. Lots of topics to discuss today with Lyn and I really look forward to this discussion. Just some housekeeping, what’s going on in our end? Quite a lot. It’s very, very busy as always before Christmas. I attended lots of lots of conferences. I did a keynote at the Dubai precious metal Summit, another one at the Precious Metals Summit in Zurich, with all the mining companies, then I visited a family office conference in Portugal.

We’re currently setting up a new fund, a very active gold fund, that invests in the whole spectrum of the gold universe, especially the mining space, but not a stubborn long only approach but rather a very active approach. So that keeps us very busy. And then obviously, our existing funds, es- pecially the two funds that combine Bitcoin with gold, doing tremendously well at the moment, so we’re quite busy meeting with new and existing clients and potential clients.

We’re already working on the 2024 In Gold We Trust report, we will put out the new chart book on gold very soon. As you know, we’ve got a quarterly Bitcoin chart book now as well. So yeah, it’s not boring over here. But I now really look forward to talking to Lyn.

Lots of people that I highly respect in the industry has extremely high respect for your work and your efforts and your views on the market that are slightly different, perhaps because you’ve got an engineering background. Let me start with your new book, it’s called Broken Money. It’s 500 pages, it’s an excellent read, I am not through the whole book, I’m somewhere on page, 270 – 280, roughly 50%, but I love it. You go through monetary history. One quote that I like where you say, gold is like the king of commodities, and like in a game of chess, the King may be the most important piece, but the queen is the most useful piece. That’s what you’re writing in regards to silver. I think that’s, that’s really nice wording, but I think it’s a must read for everybody that is interested, not only in sound money, but in our monetary system and the topics of inflation and as- set allocation in this environment. It comes highly recom- mended and a big congratulations on that fabulous book. Lyn, could you briefly explain I know it’s not easy, but what wasbthe idea behind the book? Why did you come up with the title Broken Money?

Lyn Alden: I got a lot of questions like: “Where should I start with your research, you’ve done kind of so much for so many years, and over time some of the pieces get a little bit dated, some of them change, it’s hard to know where to start?“. I wanted something kind of more holistic, that kind of summarizes my view on a lot of things and present new things that I haven’t really written about. So I can say, well, here’s where you start, you read Broken Money, and that’s helpful. Basically, I wrote the book because I couldn’t not write the book. It was my highest calling that year. It was the thing that I would get distracted thinking about that I always wanted to work on, that I would get into flow state while working on.

Broken Money, the core theme is viewing the past, present and future of money through the lens of technology. A lot of monetary history books focus heavily on the political decisions, which are important, they affect the timing of all sorts of things, which country gets ahead of another country because they made certain strategic decisions ahead of time, or things like that. But I think the bigger theme is how technology drives things, right? Politics can affect things temporarily and locally. Whereas technology drives things forward, kind of permanently and globally. If you invent refrigeration, for example, that changes almost everybody’s lives in the world, and permanently as long as we don’t have like a civilizational collapse. We never unlearn how to do refrigeration. Whereas a lot of other political decisions are more temporary, more geographically constrained.

I focus heavily on the technological aspect, especially given my combined engineering financial background. I’m not, I’m not a political historian, but viewing it through the lens of technology is helpful. I was also really fortunate to have Joachim Book be my editor. He has a master’s in financial history from Oxford. In addition to my work, a proper historian helped me research and fact check more than just edit. He played a key role in helping elevate the quality of the book to a level that’s above what I could have gotten if I didn’t have a really good fact checker and source expert.

The key theme is money through ledger technology, past, present and future, with a couple of key sub-themes in there. One key sub-theme is to look at how credit theories of money and commodity theories of money are kind of describing the same thing, but in different ways. It’s kind of like that fable of the elephant. There’s three blind men that are touching parts of an elephant, one’s touching the task, another was touching the leg and one is touching the tail, and they’re all arguing about what they’re touching. But they’re all getting a subset of the elephant. I go through that process of what is money, what is credit money, what is commodity money, and how they are interlinked. Another key theme, especially, technologically is the idea that the invention of the tele- graph had a much bigger role on monetary history than many people realize. Prior to the Telegraph, sending information over long distances, especially with high bandwidth, so anything other than fire signals in the night, was inherently a slow process, it could only move at the speed of matter. Ships, horses, and by foot. Gold and silver and physical monies and information moved at roughly the same speed, even though some paper instruments could make it more efficient for verification and traveled stuff. But with the invention of the telegraph, that speed gap completely blew open. We could now communicate worldwide, especially over decades wants these telegraph cables were actually adopted and go across the oceans and things like that, and all the technologies that have come since.

But ever since we entered that telecom age, the ability to send information very quickly around the world means we can also perform transactions around the world, but we can’t settle those instantly, we can’t just teleport gold to somebody. We increasingly relied on more and more abstraction, more and more chains of credit, and gold would more tend to be centralized and rarely taken out of the banking system, because if it’s in the banking system, if you have a deposit, rather than, say, gold coins under your mattress, you’re now part of this interlinked system. You can now send money and receive money far more readily. A big part of the book focuses on the implications of that speed gap. Some of them are good, it’s obviously good to have fast communication, the telegraph linked the world together, but it did have some negative implications for money, because it basically gave bankers and central bankers a lot of arbitraging power, for that speed gap relative to the verification and physical transport and settlement of gold.

It takes a somewhat technological determinist view of why not just some countries left the gold standard, but basically every single country left the gold standard. Because even though gold was a really good savings asset, that speed gap was very difficult for it to overcome. So that’s a big theme, then the last part of the book gets into things like bitcoin, stable coins, central bank digital currencies, the two main paths of a digital money future we have. The last point is, in the current system there are 160 different fiat currencies, roughly. And they’re all in these little silos, they all have a local monopoly in their jurisdiction. They have very little salability outside of their jurisdiction, except for the dollar and a few other top currencies, and that is largely enforced due to the legacy system. You can only really get money, in size, in or out of a country in two ways. One is physical ports of entry, you can bring cash or gold through an airport, obviously, you’re usually tightly limited there, usually under $10,000 worth, sometimes less. The other way is wire transfers in or out, but those are completely controlled by government and central bank regulations. They get to decide if I sent dollars to someone in another country, does that person receive them in dollars or do they get converted to local currency at the official exchange rate, whatever it might be. And even FinTech companies are just really mostly overlays on top of the correspondent bank- ing wire system. They just basically have accounts in multiple jurisdictions and can make that those go quicker, but they’re still usually reliant on the underlying banking.

With things like bitcoin, stable coins, and there’s even gold-backed stable coins. What all these technologies do is crack open these 160 different silos, and allow monies to compete globally once again. So now you can bring infinite value density of bitcoin or stable coins through an airport by memorizing 12 words for example, or if I pay a graphic designer in Nigeria, she can hold up a QR code on a call just like this, and I can pay her and she gets Bitcoin or stable coins or whatever she asked for in her invoice. She can receive it and it just goes around her local banking system, as long as, from my perspective, I’m not breaking any American laws. I can’t really necessarily hire like an Iranian graphic designer. But, as long as I’m not sending money to a sanctioned country, this is now a method to get value to someone in the money she wants, rather than being stuck with the local system. As long as she has access to email, DM’s, video and basically internet connection, she can now bypass those prior two methods. The world’s becoming more interconnected in terms of money and I think that has big implications going forward.

Ronnie: Lyn, let’s come back to a chapter that you actually wrote for our 2021 In Gold We Trust report, it was called “The Long Term Debt Cycle”, and you completely nailed it when you said that we’re seeing that long term fiscal, but also monetary policy regimes string together over the decades and they are now at some degree of a breaking point. You brilliantly described the inflationary threat that we were see- ing, I just reread that chapter and it was brilliant and spot on. Let’s do a little update to this topic of the long-term debt cycle. With the US and China, Chi- na’s not doing so well. Europe where a large part is already in a recession, while the US held up really well. On the other hand, I think the budget deficit is roughly 8% when you officially have full employment, so there’s an enormous amount of fiscal stimulus. Now we’re seeing that GDP growth for the fourth quarter is 1.2%, it’s clearly trending down. But then on the other hand, we’ve got elections coming up next year and I think it’s going to be a really nasty election campaign, and I think it’s going to be really dirty and hard to follow. What’s your view on the long-term debt cycle? Where are we and what would you expect when it comes to the US economy over the next couple of quarters? Are we entering into a recession?

Lyn: Yeah, it’s a good question. I think what makes this environment more unusual, is that on the mon- etary side, there’s so much tightening. If you’re in an interest rate sensitive industry, if you’re doing commercial real estate, if you’re doing residential real estate and you’re dependent on volumes and turnover. If you’re a small business that has to rely on bank credit for your financing, these areas are struggling greatly. If you do industry by industry basis, many of them are in deep re- cessions, and have been. On the other hand, if you’re not very interest rate sensitive, and you’re on the right side of the very large deficits, you’re pretty fine. If you’re in the military industrial com- plex, if you’re anywhere near DC, or other kinds of just real-world businesses. A key example I like to make is, if you’re an upper middle class, retiree, or near retiree, for example, you’ve built up a lot of assets, you own your own home, you might have a low fixed rate mortgage attached to it, and you own a lot of say, money market funds and T-bills and stuff like that. Higher interest rates actu- ally stimulate you, because your debt is still fixed, any debt you might have, while now you’re actu- ally making more income from your investment. The government’s interest expense is someone else’s gain. That doesn’t have the same sort of velocity or propensity to spend that a stimulus checks to a working class person would, because their income and expenses are roughly matched. If they get a burst of income, they’re likely going to spend it on consumer goods quickly.

Whereas if you’re wealthier, and you get more money, you don’t necessarily spend all of it, some of it might just be saved. However, you’re more likely to do international travel, you’re more likely to buy luxury goods, you’re more likely to help your kids and grandkids, if one of them is struggling and they have a wedding coming up, you might chip in or you might help them get their first house. So that money does enter the economy, just in a slower way. We’re seeing this really sharp diver- gence between fiscal policy, which is very loose, and then monetary policy, which is pretty tight. Ironically, the tight monetary policy feeds into the loose fiscal policy by blowing out the interest expense of the government. If you take a step back, the long-term debt cycle is fascinating and that’s part of what I started studying aggressively after 2017 to figure out how this normally works. Because if you go back and look at the prior major long term debt cycle in the US and much of the developed world, which would be the 1930s and 1940s. These debt bubbles tend to happen with a one two punch. So first, you get decades of private sector debt accumulation, very, very high leverage ratios. Then eventually when interest rates hit zero, but that’s still not enough, it all blows up.

That’s generally a disinflationary environment because credit is being defaulted on which destroys part of the broad money, banks are failing and that’s a very disinflationary environment.

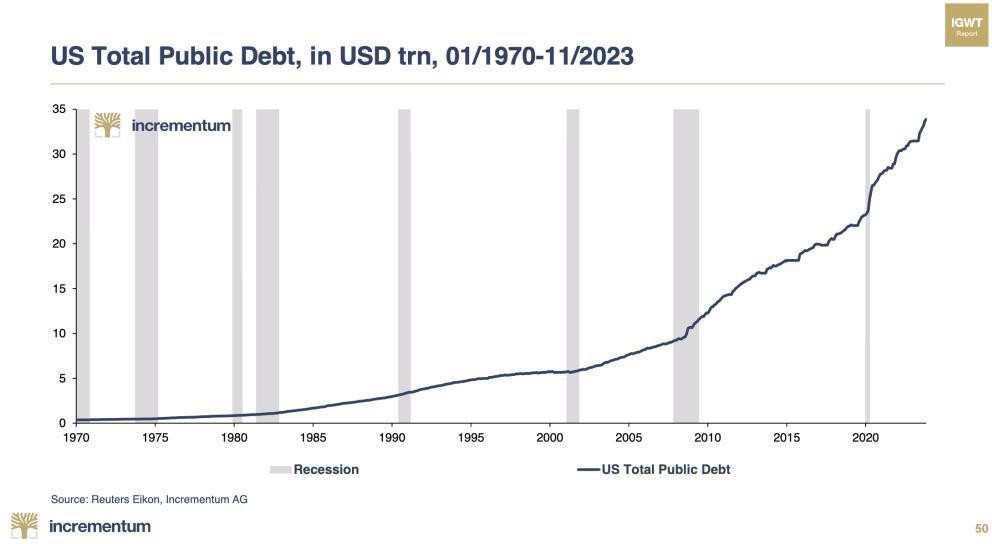

What happens is that becomes intolerable to people, and there’s rising populism and everybody focuses on what to do about the popped bubble. No one focuses on why the bubble was caused in the first place, but the end result is then basically printing a lot of money, a lot of that debt eventually gets transferred to the public sector. Usually there’s bank recapitalizations, there are stimulus programs there’s decreased tax revenue from economic stagnation, while expenses are still often relatively fixed or increasing. A lot of that debt doesn’t de-leverage nominally as much as you’d expect, and a lot of it gets transferred onto the public sector. Then, a decade or two later, when the public sector is over leveraged, that’s a very different environment. That tends to be more inflationary environment, because whenever they run into an inflation problem, the normal approach by a central bank is to raise interest rates. But if there’s so much public debt, that actually blows out their interest expense even more, and that increases the fiscal deficit, which can be stimulatory and inflationary. That’s the environment that we find ourselves in, which is that the whole 2008 crisis, and the decade that followed was the disinflationary private sector debt bubble, and a lot of that debt was transferred to the public sector in terms of bank recapitalization to stimulus programs, and it hurt tax revenue and all that kind of thing.

Now we have a demographics issue, so the baby boomers are retiring and they’re consuming but not producing as much anymore. That’s a strain on the system, both in terms of Social Security, Medicare, and just overall consumption relative to workers to produce them at least until technology can fill that gap. A sovereign debt bubble as it starts to become untenable, starts to actually be inflationary. The way to think about that is, the United States the past 40 years saw higher and higher debt as a percentage of GDP, and lower and lower interest rates. That combination actually kept interest expense pretty static, especially relative to percentage of GDP. The problem is that when you hit zero, and then you start going sideways or up in terms of interest rates, while the debt as percentage of GDP is still increasing, and it’s still very large deficits, that’s when you start to run into a fiscal spiral, because you’re paying higher interest expense on your large debt and deficits.

That’s where the United States find itself and the US also has a trade deficit structurally. You’re at very large twin deficits, double digit percentage of GDP twin deficits, which are a recipe for a problem. Now, that’s offset by the fact that the US has the global reserve currency. By default, central banks around the world hold the currency. They’re not buying Chinese yuan, they’re not buying Indian rupees, they’re not buying Canadian dollars. There’s very strong network effect around the dollar, in that region a little bit the Euro, a little bit in in say, the UAE currency, but mostly the dollar.

So, you have that global demand. There’s also something like $13 trillion in official BIS estimated dollar denominated debt, which is all basically inflexible demand for dollars, servicing that debt, any hope for paying that debt back, is all demand for dollars globally. There’s this tug of war between the United States running this big fiscal train wreck, while there’s still demand for its currency, and then the rest of the world slowly trying to get off of that, with the caveat that network effects are very powerful. If we all if you all agree that we don’t want to be in Twitter or X anymore, we want to go build this other system. It’s hard to have that happen in critical mass. If we all decided we don’t want speak English anymore, we want to speak Mandarin, that’s going to be incredibly unlikely. So, however you measure it, it’s very hard to do and it takes time. Languages don’t break, but financial things can break. Language is probably the hardest network effect to change, finance is not that hard but it is a very hard thing to change.

That’s the dilemma we find ourselves in, which I think that the developed world, because there’s so much sovereign debt now, and then especially the United States which is running very large fiscal deficits, is likely to have above target inflation for a while. I think it’s only going to go below their inflation targets during recessions. Basically, whenever they’re not in a recession, whenever they’re in a period of economic expansion, it’s likely to have inflation associated with it, because there’s very large fiscal deficits and then there’s very tight commodity supply side, infrastructure supply side worker supply side, these things are constraints against those very large fiscal deficits. Europe has its own issues, where there’s generally fewer fiscal deficits but also less energy security. Japan, they’re kind of on their own drum where they have better energy security than Europe because of better policies. They don’t really shoot themselves in the foot as much as Europe does with its own energy security, but they have very high public debt, so they’re in the same trap where if they raise interest rates, ironically it can potentially be pro inflationary. Because if you have 250% debt to GDP and you raise interest rates, you’re actually pouring more and more money out into the private sector. Somewhat offset by the fact that you’re also pulling some Japanese capital home, because Japan has decades of accumulated trade surpluses, they have a positive net international investment position, they’ve invested over the world. Raising interest rates is kind of a two-edged sword for Japan, because if they raise interest rates it makes, especially Japanese people more likely to be fine holding their currency, relative to FX hedged foreign currency and things like that, foreign bonds. But it also means that the deficits are going to completely blow out, because their interest expense becomes untenable. So that’s basically the whole Western world, including Japan, in this context of the whole developed, Western aligned axis is just facing a long-term fiscal issue, which is, I think, ultimately resolved by inflation.

Ronnie: In your book you’ve got a section on the on the fiscal spiral, and you mentioned the possibility for the government to revalue their gold in order to recapitalize the balance sheets. First of all, how exactly would this work and do you think that we’re already close to such a historic decision, or is this still five or 10 years in the future?

Lyn: I would say it’s probably in the five+ year range. These things are nonlinear, though. So, I wouldn’t be shocked if it happened three years from now, or 10 years from now. I don’t think it’s going to happen in the next year or two. Every country has a different legal structure for how it works. But for example, in the United States, and Jim Rickards and Luke Gromen has talked about this. I’ve went, and looked at the Fed manual myself, just to kind of see the text and see how it works. But basically, in United States, we have the Treasury general account. That’s basically the federal government’s checking account, when they issue bonds, the money shows up in this account, and when they spend money, it comes out of this account. That account has varying cash levels based on what’s going on. In the United States there’s enough legal structures in place that you can’t just print money without creating associated debt with it. Money comes into existence largely because of debt, that’s how they’ve structured the system. But one of the very few workarounds is a gold revaluation. So, if the Treasury instructs the Fed to change the official price of gold, then basically that fills the TGA up by that amount. That’s basically creating money without creating associated debt. Instead, what they’ve done is devalue their currency officially. For starters, they could increase it to the current price of gold, right. So instead of being $42 an ounce, they could make it $2000 an ounce and that gives him several 100 billion dollars to spend without increasing debt. When that happens, it’s pro liquidity, it’s pro inflation, it’s stimulatory, it’s a mild currency devaluation.

Ronnie: That’s like the deficit of a couple of months these days. It doesn’t really move the needle.

Lyn: Exactly, so the next step would be saying: “Okay, well, official gold price is now double” and that doesn’t necessarily affect things right away, but what it does is, now the government has like a trillion dollars to spend, without issuing debt, that’s a decent amount of stimulatory inflationary type of monetary expansion. It would probably be good for gold, Bitcoin, commodities, real estate, equities, and not great for cash or bondholders. That’s basically the reason why it’s nonlinear is because if that happens, that can instantly change everyone’s perceptions domestically and globally. At those small numbers, the effects are material, but not huge. But if you’re a foreign creditor nation holding a lot of treasuries and they do that, that’s the kind of thing that can change the reserve currency system in a similar way to freezing Russia’s reserves after the invaded Ukraine. These are kind of like historic moments that a lot of countries of the world say “wait a second”. There’s more risk here than I had thought the prior day, right. So that’s basically a mechanism that any country with gold in its central bank or balance sheet can do, they can revalue their currency relative to gold, they all have their own legal mechanisms, either written or implied, that they can turn to.

That can kind of reset the problem and then you can raise rates from there to get back to a period of kind of real, real rates and austerity. But then the question is, have you permanently destroyed trust in that, right. The 1971 event damaged trust, but it didn’t permanently destroy trust. In the second half the 70s and in the 80s they got the world to accept treasuries and dollars again. That’s the gamble that they would have to do. I think we’re still a long way off, because before they would do something like that, they’re going to drain the reverse repo facility and then there’s other kind of levers they can pull, they can change the leverage ratio for banks to allow banks to hold more treasuries, the Fed can go back to slowly accumulating treasuries and saying it’s not QE, it’s for financial stability, or they can hand wave things for a while and it still has material effects, it’s still pro liquidity when they do things like that. All being average, is pro inflationary, pro liquidity and only when things get truly messy, I think, would they risk resorting to that gold lever, if they even pull it? I mean, there’s all sorts of mechanisms they can do from yield curve control to gold revaluation. But these are historic things that have happened in the past, have happened in our parents and grandparents’ lifetimes, that we assume it’s crazy to even talk about today. But I think that these types of things will be happening in our lifetimes.

Ronnie: Nobody would have expected 18 months ago that the Federal Reserve would be able to raise interest rates that aggressively without completely crashing markets. I just had a look at most of the 2024 outlooks, and it’s goldilocks. All over everybody’s super optimistic, soft landing, S&P goes to $5000, 10-year treasuries going down to 3.2%, something like that. So, everything’s fine again. But I think in the end it’s all about the credibility of central bankers. Somebody once said that central bankers are the high priests of our monetary system. At the moment, everybody believes that they manage it really well. Lyn, two more things that I would love to discuss. We’re running out of time, but two questions, first of all, regarding Bitcoin, we’ve got the halving coming up, and there’s prob- ably lots of ETFs being issued, probably at the beginning of next year, and I think this will probably be the next stage of adoption, especially in the mainstream financial world where if you’re in financial advisor you can say well, all this stuff with the wallets and that’s too complicated, but if there’s actually an ETF or Bitcoin ETF issued by Blackrock or Fidelity, that’s actually something that I can recommend to my clients. So, a brief outlook, what’s your take on Bitcoin at the moment? I know that there’s still very few people that actually like Bitcoin and gold, we get lots of criticism from the gold camp but also from the Bitcoin camp. It’s a very emotional discussion, from my point of view gold has a pretty long track record as money and as monetary insurance, while Bitcoin is hardly a teenager. But so far, it’s doing tremendously well. So, a quick view on Bitcoin and then also, what excites you most for next year, for 2024? And what worries you the most for the next year in terms of investments?

Lyn: Yeah, so I I’m one of those people that likes both gold and Bitcoin, for different reasons. I think they serve different purposes. For Bitcoin, I think there’s a number of factors that are shaping up to give it the next bull market. Basically, the spot ETF can add demand for it. Any sort of commodity futures ETF generally has problems with performance when compared to the underlying commodity, and they’re not super attractive. Bitcoin in over the market trusts is also not super attractive to advisors. So, an actual exchange listed spot ETF by a major financial asset manager is a big deal for accessing tens of trillions of dollars of capital that’s currently not really allowed to invest in Bitcoin related products, other than maybe some miners or MicroStrategy around the margins. So that is a new source of demand. The halving takes away half of the new supply, and then the other factor is that during bear markets, the fast money all leaves and the long term convicted money keeps buying. So more and more Bitcoin ends in strong hands. People that buy and rarely sell, they literally take cold storage of it, and do all that, and that ends up tightening the market. Basically, a lot of the liquid supply has been taken off, and it only takes a small amount of new demand to come in, and the price starts moving a lot, because I’m not selling my bitcoin at current prices.

I’m like a price and inflexible holder, there’s a very big band for where I would consider actually selling some bitcoin, and there’s a lot of people like that. That’s the hodl-wave cycle that it goes through. The other factor is that in my research, Bitcoin is the asset that is most closely correlated with global liquidity. There’s a couple of ways to measure that, Michael Howell from Cross Border Capital probably has the most sophisticated liquidity metric, the one I use is simply global M2 denominated dollars. If you look at global broad money supply, denominated dollars, you’re basically measuring how much credit creation is happening, how much money printing is happening, how’s the dollar doing relative to other major currencies, which matters because so many countries have dollar denominated debt, as the unit of account for the world, in many aspects. That is highly correlated with Bitcoin, when that’s going up, normally bitcoin is going up, when that’s going down, normally bitcoin is going down. Especially when you look at these things in rate of change terms. Having a view about liquidity helps if you are trying to have a positive and negative view on Bitcoin. So overall, I view 2024 as a mixed environment. There are some industries that are absolutely suffering and other ones that are just like “recession? What recession?” So, people are debating between hard landing and soft landing, I’ve been referring to it as an emerging market landing, which is if you look at an emerging market with a recession, what does it look like? Well, as the prices usually go up in local currency terms, they don’t do well in dollar terms or gold terms, usually, people are still relatively employed, but with a general sense that things aren’t going well, like their overall purchasing power is not great, even though it doesn’t feel like a developed market recession. In a way it’s like this big disinflationary cycle and you have mixed systems where if you’re an emerging market corporation that is defaulting on your dollar debt, you’re having a bad time. Whereas if you’re an emerging market exporter, and you’re selling things for dollars, and you’re hiring people that you pay in the local devaluing currency, you’re doing fine. It is like a very different type recession; it feels very different.

I think that developed countries are going through a similar type of landing, which is that I don’t think it’s like a big 2008 style disinflationary crash. Instead, it’s this high nominal environment, but that depending on where you are in the economy, it can feel like a recession, or it can feel like not a recession. Generally, my view on Bitcoin and gold is constructed for the next two years, rather than a 12-month time frame, I like to give myself a 24 month timeframe, because that’s how long I think this next liquidity cycle could take to play out, maybe even three years. But I expect basically Bitcoin to do well, I expect gold to do well, I’ve been tracking gold see if we break all-time highs, it has. Now the question is, can it stay above it? Can it retest it and hit a higher low and keep going from there? It already has in most other currencies? I consider them at different speeds. So for example, I do expect Bitcoin up from gold over the next say two years. But of course, you’re taking on more volatility to get that potential outperformance and so I expect both assets to do well at their own speeds. I’d also look at certain emerging market equities, you have to obviously be very selective. I’m generally constructive on Latin America overall and certain parts of Southeast Asia. I think that those are the types of areas where I think that there’s, there’s value and opportunity.

Ronnie: Lyn, thank you very, very much for your time, now is the time to say where we can find you what services you offer. Let us know a little bit more about what you do and where we can find you.

Lyn: Sure, people can check out www.lynalden.com, I have a free newsletter that people can sign up for, it is actually pretty in depth. Then I also have a low cost paid research service, Lyn Alden premium, if people want more regular updates about the markets or specific investment opportunities. Then lastly, check out Broken Money on Amazon or elsewhere. If you want an overview over just how money works, and a lot of things that people maybe haven’t considered.

Ronald-Peter Stöferle, CMT

Ronni is managing partner of Incrementum AG and responsible for Research and Portfolio Management.

He studied Business Administration and Finance in the USA and at the Vienna Univer- sity of Economics and Business Administration, and also gained work experience at the trading desk of a bank during his studies. Upon graduation, he joined the Research department of Erste Group, where he published his first In Gold We Trust report in 2007. Over the years, the In Gold We Trust report became one of the benchmark pub- lications on gold, money, and inflation.

Since 2013 he has held the position as reader at scholarium in Vienna, and he also speaks at Wiener Börse Akademie (i.e. the Vienna Stock Exchange Academy). In 2014, he co-authored the book Austrian School for Investors and in 2019 The Zero Interest Trap. Moreover, he is a member of the board at Tudor Gold Corp. (TUD), a significant explorer in British Columbia’s Golden Triangle and a member of board at Goldstorm Metals (GSTM). He is also an advisor to Matterhorn Asset Management, a global leader in wealth preservation in the form of physical gold stored outside the banking system.

Mark J. Valek, CAIA

Mark is partner of Incrementum AG and responsible for portfolio management and re- search.

While working full time, Mark studied Business Administration at the Vienna University of Business Administration and has continuously worked in financial markets and asset management since 1999. Prior to the establishment of Incrementum AG, he was with Raiffeisen Capital Management for ten years, most recently as fund manager in the area of inflation protection and alternative investments. He gained entrepreneurial experience as co-founder of Philoro Edelmetalle GmbH.

Since 2013 he has held the position as reader at scholarium in Vienna, and he also speaks at Wiener Börse Akademie (i.e. the Vienna Stock Exchange Academy). In 2014, he co-authored the book Austrian School for Investors.

About Incrementum AG

Incrementum AG is an independent investment and asset management company based in Liechtenstein. Independence and self-reliance are the cornerstones of our philosophy, which is why the four managing partners own 100% of the company. Prior to setting up Incrementum, we all worked in the investment and finance industry for years in places like Hongkong, Frankfurt, Madrid, Toronto, Geneva, Zurich, and Vienna.

We are very concerned about the economic developments in recent years, especially with respect to the global rise in debt and extreme monetary measures taken by central banks. We are reluctant to believe that the basis of today’s economy, i.e. the uncovered credit money system, is sustainable. This means that particularly when it comes to investments, acting parties should look beyond the horizon of the current monetary system.

Cautionary note regarding forward-looking statements

THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN INDEPENDENTLY VERIFIED AND NO REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED IS MADE AS TO, AND NO RELIANCE SHOULD BE PLACED ON, THE FAIRNESS, ACCURACY, COM- PLETENESS OR CORRECTNESS OF THIS INFORMATION OR OPINIONS CONTAINED HEREIN.

CERTAIN STATEMENTS CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE STATEMENTS OF FU- TURE EXPECTATIONS AND OTHER FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS THAT ARE BASED ON MANAGEMENT’S CURRENT VIEWS AND ASSUMPTIONS AND INVOLVE KNOWN AND UNKNOWN RISKS AND UNCERTAINTIES THAT COULD CAUSE ACTUAL RESULTS, PER- FORMANCE OR EVENTS TO DIFFER MATERIALLY FROM THOSE EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED IN SUCH STATEMENTS.

NONE OF INCREMENTUM AG OR ANY OF ITS AFFILIATES, ADVISORS OR REPRESENTA- TIVES SHALL HAVE ANY LIABILITY WHATSOEVER (IN NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) FOR ANY LOSS HOWSOEVER ARISING FROM ANY USE OF THIS DOCUMENT OR ITS CONTENT OR OTHERWISE ARISING IN CONNECTION WITH THIS DOCUMENT.

THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFER OR INVITATION TO PURCHASE OR SUBSCRIBE FOR ANY SHARES AND NEITHER IT NOR ANY PART OF IT SHALLFORM THE BASIS OF OR BE RELIED UPON IN CONNECTION WITH ANY CONTRACT OR COMMITMENT WHATSOEVER.

Copyright: 2023 Incrementum AG. All rights reserved.