A global future with lessons from the past

2023 will be remembered for its tumultuous wars and fervent activism, yet it was marred by a wide lack of outcomes, potentially rendering it a “lost year” in history.

The tension between Western powers and their adversaries, China and Russia, persisted without fundamental shifts despite lots of strategic maneuvering. Conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, the Horn of Africa and the Congo trudged on unabated.

In the welfare states, especially Europe, the question of immigration loomed large with no clear answers. The pursuit of decarbonization and climate protection saw grand gestures and sweeping commitments. However, progress was entangled in red tape and bureaucratic complexity, overshadowing – even hampering by dogmatic policies – real and strong advancements by business.

There was relief as the dark clouds of a threatened recession dissipated and inflation moderated. Yet the calm may be short-lived as the core issues of mounting debt and an overstretched bureaucracy loom larger, with technocratic meddling in economic affairs exacerbating the situation.

Superficially, little has changed, echoing the sentiment of King Louis XVI of France, who on the eve of the storming of the Bastille, penned a dismissive rien – “nothing’’ – in his diary. It was a clear failure to recognize the circumstances that triggered the French Revolution.

The world is undeniably in crisis. Yet crises can be catalysts for either rapid decline or significant improvement.

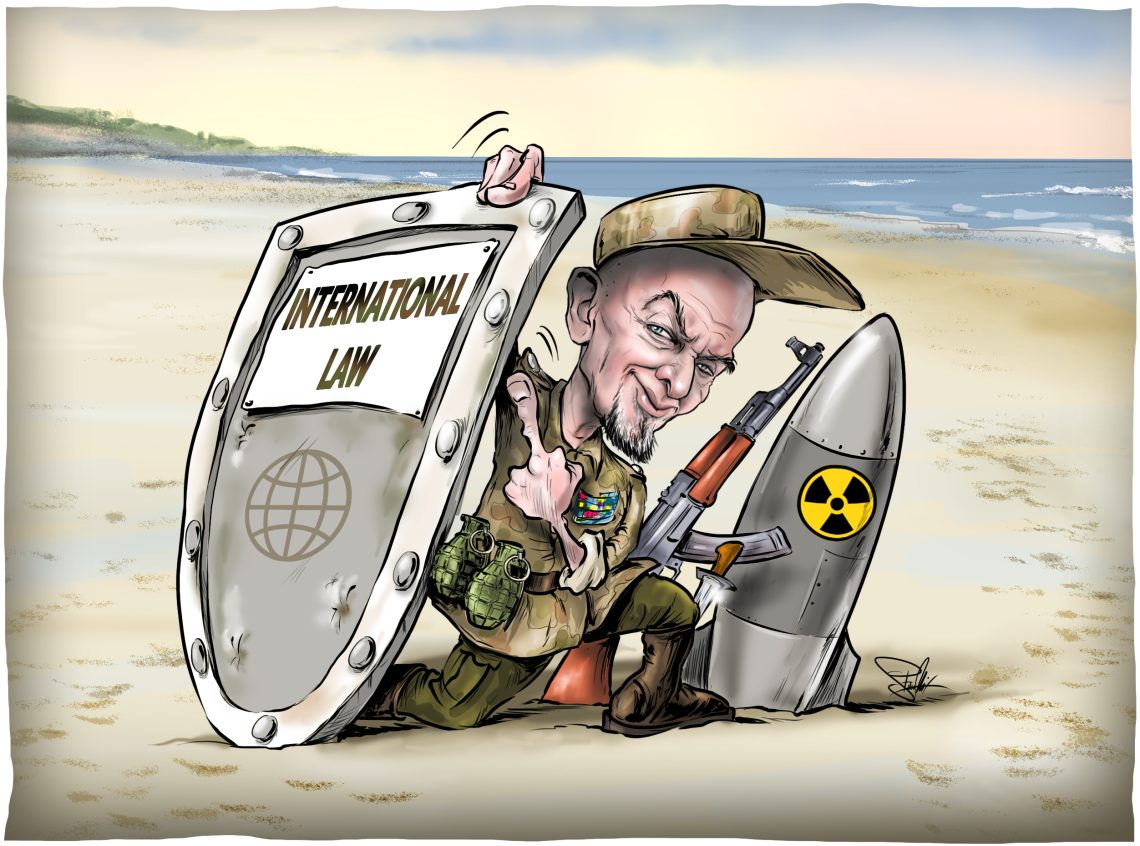

Optimism must be tempered with realism. The global landscape is indeed transforming, but many cling to old patterns of thought. The West often views international relations through a rather imaginary lens of democracy versus autocracy. Today’s “axis of evil” from the Western perspective is led by China, Russia and Iran. The West wants the Global South to take its side. But, for the most part with some exceptions like Javier Milei’s Argentina, this is not going to happen. The concept of a rules-based world order is being contested.

The Kremlin understands the emerging realities and eschews the term Global South in favor of recognizing these nations as the “global majority.” This more collaborative stance is exemplified by the evolving partnership between Russia and India as the Kremlin distances itself from Western alliances. Yet Russia’s brutal war against Ukraine underscores Moscow’s inability to reconcile its imperial ambitions with the self-determination of its neighbors.

The late Zbigniew Brzezinski, who was a sage foreign policy analyst, once declared that Russia without Ukraine would cease to be a Eurasian empire. This was true at the time. But now it is more fruitful for Russia to consolidate relations with the East, leading Moscow to strengthen collaboration primarily with China, but also with the two Koreas and Japan. However, Russian delusions of grandeur prevent it from embarking on further constructive priorities, from accepting its western borders to engaging Europe and developing Siberia.

Amid geopolitical reorientations, the necessity of a Russo-Chinese alliance is mutually recognized. Russia’s pivot to the East is a fact, but Moscow still seeks a buffer zone in Central Europe, an ambition that poses a significant threat to European security.

With elections ahead in the U.S. and socioeconomic problems in China, Washington and Beijing are attempting to smooth over trade relations. These tactical adjustments, however, do not signify a true easing of underlying tensions. China’s millennia-old aspirations for hegemony differ from past conflicts such as the Cold War. Unlike the Soviet Union, China’s quest for dominance is less about exporting its political ideology and more about affirming the supremacy of the Chinese Communist Party within its borders. Therefore, the European Union’s view of China as a “systemic rival” is a wrong assessment of the situation. But it must be recognized that Beijing is pressing for a new world order and its ambition is hegemony.

Europe finds itself in decline, yet this trajectory is not set in stone.

Other elements at play were absent during the Cold War. The Soviet Union was not an important economic factor, while now economic relations with China are crucial for every country, even more so than trade with the U.S. or Europe for many nations. Southeast Asian nations, while reliant on China economically, seek alliances especially with the U.S. for security reasons. But these nations also want to diversify their international relationships to reduce their dependencies on Beijing and Washington.

Europe finds itself in decline, yet this trajectory is not set in stone. This is a matter we will undoubtedly return to in another comment.

Economically, the global debt crisis looms large, with the potential to trigger widespread social upheaval in the foreseeable future. Intolerant nongovernmental organizations as well as governments, both democratic and autocratic, consider inequality as the root of all economic woes. However, this perspective misses the mark by overlooking the fact that shrinking the wealth of the affluent does not balance budgets nor decrease poverty. Economic growth and increased prosperity are best achieved by letting individuals and businesses thrive with minimal government interference.

Unfortunately, the trend is going in a different direction, pivoting from growth to bureaucracy. The entrepreneurial spirit is hampered under the weight of an ever-expanding regulatory web. The resulting compliance burden is an anchor dragging down productivity.

Economic inequality has dual origins. One stems from the tremendous innovations that naturally create winners in a dynamic marketplace. In such a system, free-market forces act as levelers, smoothing out disparities over time. The other cause is state overreach in which excessive legal and regulatory regulation foster oligopolies and even monopolies. Yet another insidious form of excessive state intervention is corruption.

The recent pivot in U.S. policy, dubbed the “New Washington Consensus” by President Joe Biden’s national security advisor Jake Sullivan, strays from the previous market-driven approach that spurred global prosperity. This shift favors more economic planning and government intervention through empowering entities such as the G20 and G7 without sufficient accountability. This is an attempt to establish a globally planned economy if pursued to its logical conclusion. It also neglects the fact that consensus can only be successful based on interests and not on policies.

Through whatever changes that take place, the U.S. will likely remain dominant, buoyed by its favorable geography and formidable defenses. The technological advantages it enjoys over other nations are huge. The dollar remains the global reserve currency. But its overuse for geopolitical leverage, coupled with the nation’s burgeoning debt, foreshadows a potential erosion of its financial hegemony. Furthermore, the ascent of digital currencies and other technological advancements are likely to weaken existing fiat currencies over the long term.

Encouragingly, science and technology continue to make huge progress. Paired with deregulation, they hold the promise of rejuvenating global growth, reducing poverty and easing social conflicts. This optimistic future is contingent on restraining government and supranational organizations from stifling economic dynamism and increased productivity.

This comment was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/global-future-economy/