Geoeconomics in constant change

We are living in a time of immense geopolitical shifts. This is not surprising, as change is a normal occurrence. However, there are periods when changes take place more rapidly and on a larger scale.

Shifts in geopolitics can be driven by a variety of factors, including technological, demographic, and environmental developments, as well as political movements and changes in society. While single incidents can trigger large disruptions, they often result from these factors accumulating over time. Such disruptions can be exacerbated when politicians block developments in the interest of maintaining the illusion of stability and security.

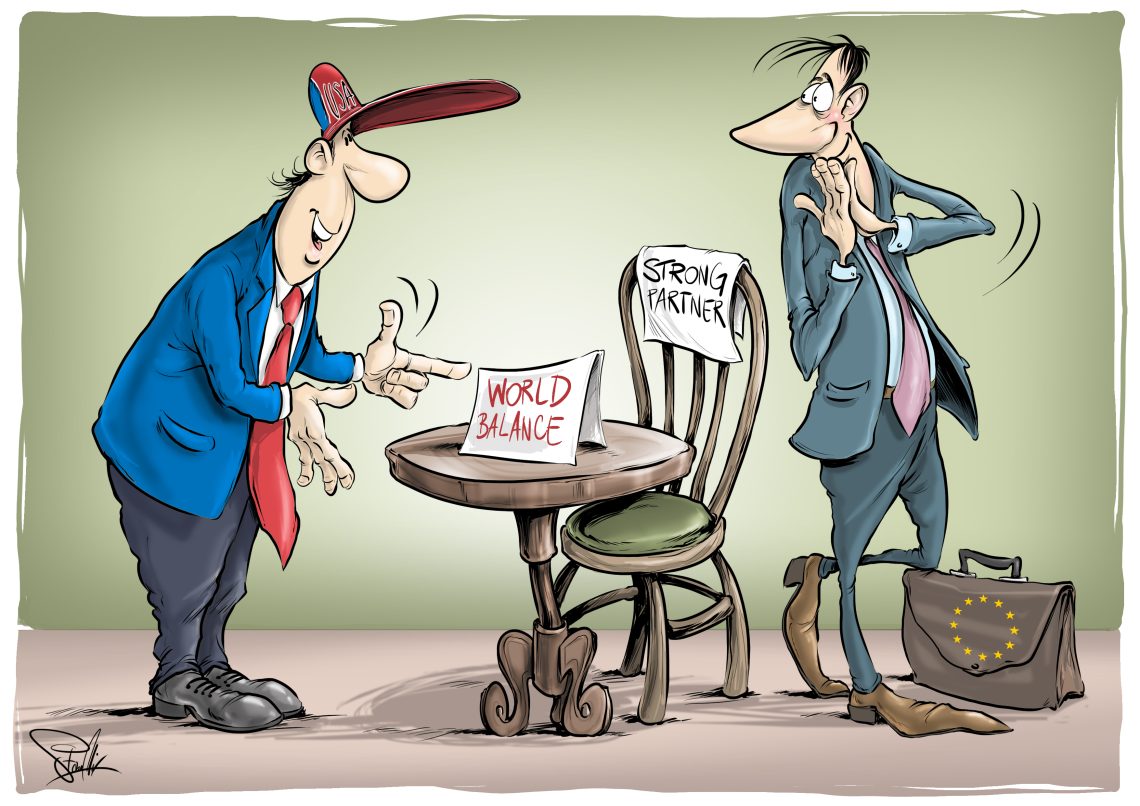

It is widely acknowledged that the world is becoming multipolar politically. The West aims to defend the so-called “rule-based liberal world order,” which requires a “protecting power.” Historically, this role has been held by the United States since World War II, and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U.S. remained the dominant hegemon.

This system is now being challenged, particularly by China and Russia, but also by countries in the Global South who no longer want to be dominated, even by friendly democracies in the Northern Hemisphere. A real systemic and hegemonic conflict has arisen between China and the West.

Economic power shift

There are also parallel shifts in economic power. For the 200 years up until the 1980s, the North Atlantic, specifically the U.S. and Europe, was the global economic powerhouse. However, this is no longer the case.

China, with its 1.4 billion inhabitants, has become the world’s second-largest economy, after the U.S. Four factors were behind its rise: a growing population, a supportive environment for entrepreneurship, technological development and abundant global trade. The four largest economies by gross domestic product are now the U.S., China, Japan and Germany.

It is widely believed that China will surpass the U.S. in terms of economic size in the near future. However, it is important to approach this prediction with caution.

In an increasingly technocratic world, we tend to rely on theoretical models and extrapolation, rather than using the art of scenario planning. Economics is not an exact science and politics is more of an art than a discipline. Unfortunately, there is another parallel with art in that there are more mediocre and poor players than outstanding ones. Human irrationality, combined with forceful political interventions in the economy, adds incompetence to the existing complexity.

The proposed cure is based on the same principles that got us into the crisis in the first place.

A second problem is today’s focus on risk. The World Economic Forum often emphasizes recognizing the largest risks based on a census, which can add concern and even fear to decision-making, rather than identifying real opportunities.

This also opens the door for certain nongovernmental organizations and irrational messages. A typical example is Oxfam and its questionable figures on inequality. While fighting poverty is certainly important, the inequality debate has led to an odd result where people, including many politicians, are more concerned with some people being rich than trying to eliminate poverty.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres added to the panic at Davos by comparing today’s economic situation to a category five hurricane in terms of potential destruction. While the situation is certainly critical, the remedies offered are again based on the sectarian dogma of the primacy of politics, rather than sound, pragmatic solutions. The proposed cure is based on the same principles that got us into the crisis in the first place.

A new top tier

The first question to consider is whether China will truly become the world’s largest economy. Of the four previously mentioned factors that have driven China’s unparalleled growth, two have already become redundant. First, the population is now in decline and the country is facing a severe aging problem. Second, President Xi Jinping’s new policy, which focuses on strengthening primarily state-owned businesses, limits entrepreneurial drive.

Additionally, geopolitical tensions are leading to fragmentation, which could limit international trade with China. That would be very negative for China’s growth and an important factor to consider for Western, especially European, business and economic strategies. Can we maintain prosperity with reduced trade with China? Where is the West strategically dependent on Chinese products or those from countries within China’s sphere of interest?

The EU could be a major player if it were to have less regulation and protectionism.

Given the above, it is quite probable that the U.S. will maintain its position as the world’s biggest economy for a while. In fact, the European Union could be a major player too if it were to gain a better-functioning internal market with less regulation and protectionism. Reducing bureaucracy at the national and Union level could boost Europe’s global competitiveness.

But there are other countries that will likely join the top tier of global economies. India will soon become the world’s most populous country and has strong growth rates, although it is starting from a lower base. India and the ASEAN countries could potentially replace China in global economic interactions.

Europe has tremendous opportunities in its neighborhood. Africa, with its demographic and resource potential, should be a focus for Europe. This would require European politicians to concentrate on free trade and to help protect business investments and activities in areas of weak governance. On the other hand, European protectionism toward African products would need to be abandoned. The EU currently implements excessively protectionist regulatory measures under the pretext of consumer protection.

At the moment, it is difficult for Europe to have a constructive relationship with its direct eastern neighbor, Russia, due to the latter’s brutal invasion of Ukraine. However, in the long term, it will be essential for the Old Continent to find a way to coexist with Russia. This is also in Moscow’s long-term interest, as the challenge from China is much more dangerous for Russia than the old fear of a European attack. A Chinese-controlled Siberia would be a nightmare for the free world.

These are some of the issues that we must keep in mind when considering the geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts in the coming decades.