Productivity and innovation: Europe’s wasted opportunity

In March 2000, European Union leaders launched the Lisbon Strategy, an ambitious vision to make the EU the world’s most competitive economy by 2010. The goal was to foster a knowledge-based economy and a seamless internal market. Since then, the commitment has been repeated like a mantra – but the target date has continually been postponed.

Reality has moved in the opposite direction: In 2008, EU gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was 77 percent of the U.S. figure. By 2023, it had fallen to 50 percent.

Back in 2008, the EU’s nominal GDP was higher than the U.S. figure. Since then, a dramatic reversal has taken place. In 2024, U.S. GDP reached $29.2 trillion, while the European bloc lagged behind at $19.4 trillion. During the same period, China’s GDP surged from $4.7 trillion to $18.8 trillion – nearly equaling that of the EU.

The EU’s waning economic edge reflect a failure of governance, not of markets.

The causes of Europe’s decline are well known: lagging productivity and a growing innovation gap. In fact, European productivity has shrunk over the past three years. Contributing to this trend is the disproportionately large role of government in the economy – 49.2 percent of GDP in the EU, compared with just 33.9 percent in the U.S., according to Eurostat and the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Maybe the heaviest burden across Europe is overregulation. Moreover, Germany, the EU’s largest economy, suffers from self-inflicted high energy costs resulting from its failed Energiewende (energy transition) policy.

Innovation is further stifled by the lack of a robust capital market, regulatory barriers and a culture that penalizes failure. Public innovation funds are often misallocated for political reasons.

A case in point is Horizon Europe, a 100 billion-euro EU innovation program launched over the past decade. A study by Bocconi University and EconPol Europe found that Horizon grants have largely gone to established companies. Fewer than 8 percent of recipients were small, innovative startups. Most funds were absorbed by large corporations and research consortia that delivered only limited innovation and economic impact.

Europe boasts excellent universities and a well-educated, experienced workforce. Its family-run businesses and SMEs are dynamic and competitive by nature. There is no inherent reason the continent should lag in competitiveness. As it stands, the root causes lie in political overreach, stifling regulation and a general comfort that dampens ambition, rooted in a bloated welfare state. The recession and the EU’s waning economic edge reflect a failure of governance, not of markets.

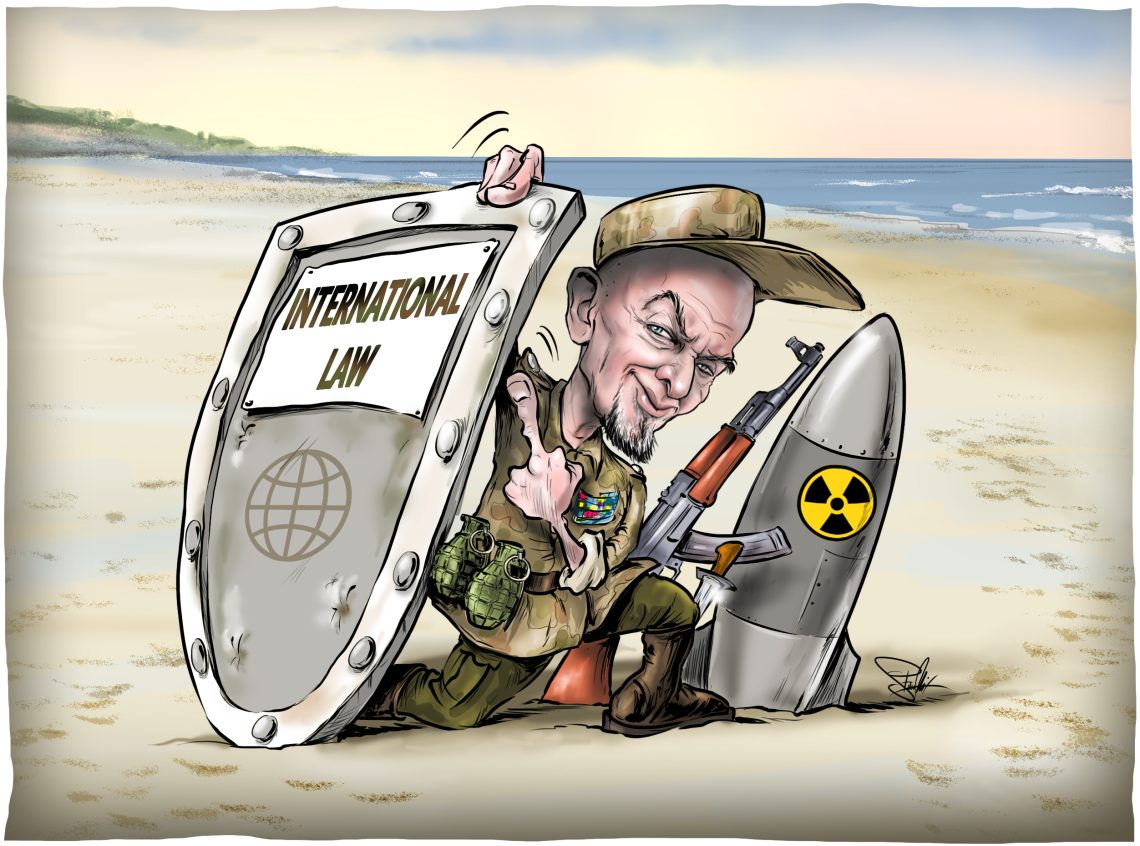

The EU has become increasingly protectionist, mainly through regulation. While convenient, this strategy is proving counterproductive. It eliminates the incentives for efficiency and creativity. The Digital Services Act and increasingly narrow interpretations of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) were intended to rein in U.S. tech giants, but have instead held Europe back in these same sectors. The AI Act and supply chain laws are similarly damaging.

Two new developments may serve as wake-up calls.

First, Qatar has warned that EU regulatory overreach – particularly in supply chain due diligence – could compel it to halt natural gas exports to the bloc. The perceived risk of fines is simply too high. That would be a major blow for countries like Germany, still dependent on Qatari gas after losing access to Russian supplies. The fact that a key supplier is threatening to walk away should prompt European policymakers to reconsider the logic of such rules.

Second, newly agreed U.S. tariffs on EU imports will put further pressure on European firms to improve productivity and competitiveness. The good news is that this is possible.

Switzerland provides a compelling example. The Swiss franc has appreciated by some 75 percent against the euro since 2008 – a currency gain that has the same economic effect as tariffs. Yet Swiss exports remain robust. Half of Swiss exports go to the EU. The country has maintained its edge through productivity, innovation and diversification. Its economy is supported by market-friendly policies and a smaller government footprint – public spending accounts for about 30 percent of GDP.

The combination of the Qatari threat, the U.S. tariffs and the Swiss example should push policymakers to rethink their regulatory excesses. Europe must cut red tape and restore market-based policies.

For now, shortsighted and politically expedient decisions are wasting talent, stifling innovation and locking the continent into a cycle of mediocrity. This is a shame – but not irreversible.

This comment was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/european-innovation-productivity/