Europe’s regulatory-technocratic suicide

Europe’s economic engine is sputtering, and real growth rates are shrinking. With a few exceptions, this is the case all over the old continent. Europe has all the ingredients of success: a well-educated population, great scientific institutions and universities and a wide range of successful companies, especially owner-managed family businesses and hidden champions. Despite that, it is losing out in the global competition. The reasons are worth investigating.

A recent study published by four leading German economic research institutes highlights the problem areas. One is bureaucratic overregulation.

A representative review of German businesses (large, medium and small) revealed that most respondents see the increasingly tight regulatory environment as the leading threat to success and productivity. National authorities and supranational organizations are cranking out new rules and regulations at the speed of assembly lines. Vast documentation is demanded to prove compliance, which eats up company resources better spent on productive work in manufacturing and services, innovation and market competition. On top of these unproductive compliance costs come frequent audits, further limiting entrepreneurial freedom.

Monster reporting system

Consider just this one example: The European Sustainability Reporting Standard (ESRS) is a colossal document counting 400 pages. It contains very detailed requirements for corporate reporting on a range of social, environmental and governance issues, updating and strengthening the earlier Non-Financial Reporting Directive. The ESRS went into effect in January 2023, and now the member states have 18 months to integrate the new rules into their national law. The first submissions are due in 2025 from larger companies with more than 1,000 employees and the businesses active in the areas ESRS considers sustainability risk, such as timber, textiles or mining. After 2026, all businesses with staff over 250 persons will have to comply – estimated 50,000 companies in Europe.

All the above creates a nightmare for businesses. It will multiply the unproductive work in national administrations, business and auditing sectors.

The reporting system is based on 1,444 data points throughout the supply chain. Besides defining environmental, human rights and labor standards, it also includes fuzzy issues, such as “work-life balance.” The reports will have to go to the Directorate General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union, one of 33 functional departments of the EU Commission. But it gets weirder.

Overlapping laws

In February 2022, the Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers put together the so-called “supply chain directive” that will come into force later this year. That directive concerns illegal actions of suppliers against environmental rules and human rights; it overlaps the ESRS, doubling the reporting burden for companies. Then, the Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs plans its own directive in the same areas, most probably not very different from these others. And then comes the EU taxonomy from the financial stability directorate, which prescribes whether enterprises are acting ecologically.

All the above creates a nightmare for businesses. Every activity, business practice and governance rule will have to be documented in a way that it can be audited. It will multiply the unproductive work in national administrations, business and auditing sectors.

Weak rationale

The reasoning underlying this straitjacket is that investors will read the reports and channel the investments in an ethical and ecological way. That is an illusion. This sort of Soviet-style central planning, ironically called “market” reforms by EU bureaucrats, produces only waste: of money, labor and material. It will create market bubbles on one side and investment gaps on the other. The German national daily newspaper Die Welt, which reports on the issue, quotes Steffen Kampeter, the CEO of the Confederation of German Employers: “businesses need labor for innovation and creation of value, not for bureaucracy.”

Rules are certainly needed. However, overregulation and unnecessary reporting obligations should be avoided. There will always be some debatable business practices in the real world, but such measures will not stop those. We need to return to trust-based systems whenever it is possible.

Undermined labor market

Another nagging problem reported by the German economic institutes is the skilled labor shortage.

Nearly all businesses in Europe complain about the dearth of skilled workers. Demography is a significant contributor to the problem, with the baby boomers retiring. Another is the administration siphoning staff away from productive work in the private sector. Bureaucracy binds labor in less effective areas. The demographic figures for Europe indicate that the labor shortage will only deepen.

Another problem is that younger people want to work only part-time – 70 or 80 percent of their regular workload – under the guise of seeking a better “work-life balance.”

The most obvious solution to Europe’s competitiveness problem would be drastically downsizing the bureaucracy. Higher environmental and ethical standards can be achieved economically and with much less effort.

At the same time, we also have millions of unemployed people. The exceedingly strict labor laws in Europe make it risky to employ people without a track record because it is difficult and costly for a business to separate from employees who do not perform. We have the welfare paradox: the labor laws, which should protect employees are, in effect, an obstacle to employing people.

Energy calamity

The German report also lists excessive energy prices. Europe, especially Germany, suffers from failed past politics in that area. In 2011, Germany renounced nuclear power, making its energy mix more expensive and overdependent on cheap gas from Russia. That led to a lot of outsourcing production to areas with low energy prices. (Lower labor costs were often a secondary factor). And in 2022, following sanctions on Russia, energy costs exploded, putting most of Europe under duress.

That hurt local production, endangering the energy-intense industries and demonstrated the limits of globalization and outsourcing of production.

What can be done?

Theoretically, the most obvious solution to Europe’s competitiveness problem would be drastically downsizing the bureaucracy. Higher environmental and ethical standards can be achieved economically and with much less effort. It was always doubtful that technocrats could develop solutions better than the market does.

However, this cure would cause many people in unproductive areas to lose their jobs – although, for most of them, temporarily. Sometimes it is necessary to perform radical surgery on one body part to save the rest. In the end, a reduced bureaucracy would boost business, and those laid off would end up in productive, often better-paying and more satisfying, lines of occupation.

Unfortunately, it is doubtful at present that any of this is going to happen.

We do not need doctrines but more common sense and flexibility in choosing the right energy mix.

Regarding skilled workers, making retirement rules more flexible could help. People who want to work longer should be able to do so without losing their pension entitlements. A mere increase in the retirement age from, for example, 63 to 65 will not solve the problem. In turn, to fix immigration policy, a distinction between refugees (from political oppression) and migrants (for other reasons, mostly economic) should finally be made. The inflow of migrants must be controlled, with a preference for those needed in Europe’s labor markets.

More room for market mechanisms

On the energy side, we do not need doctrines but more common sense and flexibility in choosing the right energy mix. For the time being, the social and political barriers to expanding nuclear power generation remain in parts of Europe – a major impediment. Ultimately, we should let the markets work their wonders on investments in energy projects – certainly inside the proper ecological parameters but free of the excessive burden of bureaucratic overcontrol.

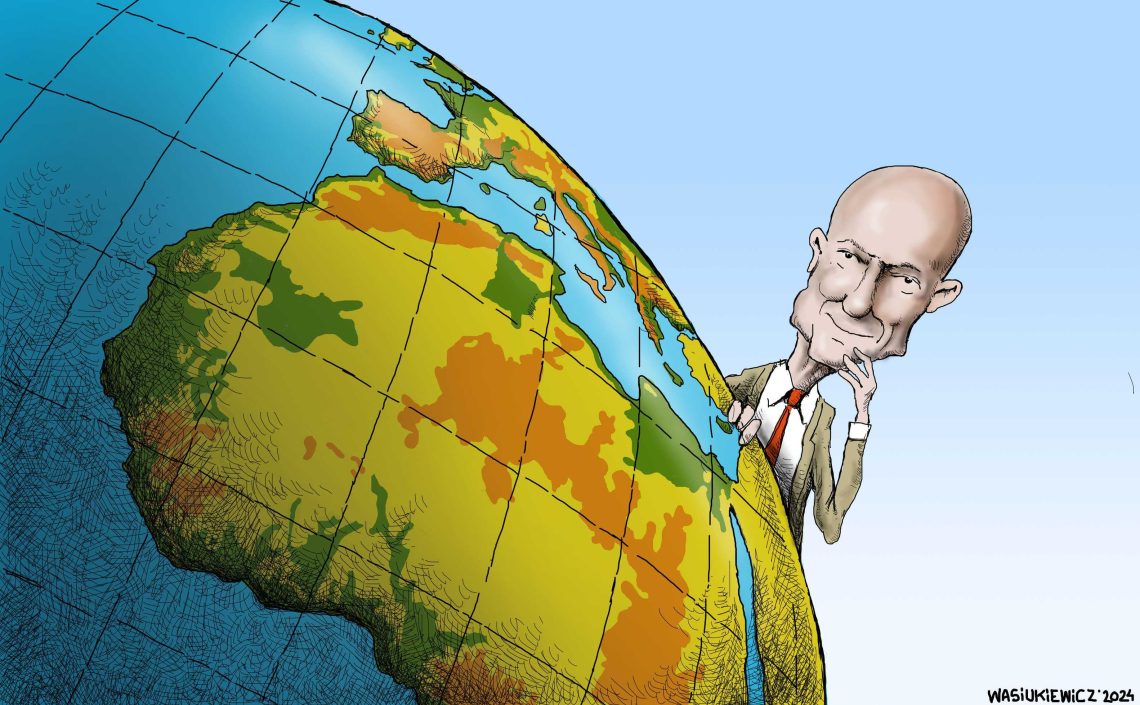

There is another critically important challenge for Europe. Trade with China – its role as an export market and a European supplier – carries geopolitical risks that must be reduced. New markets in Southeast Asia, Africa and the Americas need to be explored, and new economic partners found.

To open this avenue, however, Europe must revise its protectionist regulations disguised as consumer protection. Guarding consumer interests is essential, but the system’s overhaul is necessary to also realize the continent’s trading potential.

All the problems listed here have arisen from a mixture of “European values” hubris and arrogant overreach of the centralized bureaucracy/technocracy. Europe’s citizens must not be complicit in this form of painful suicide.