European defense expenditure: Is it enough?

Most political theories assert that protection against foreign invaders is one of the main functions of the state. However, excluding years when countries were engaged in active warfare, the proportion of global government spending on defense in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) has remained relatively modest. For instance, from the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 until the mid-1930s, defense spending accounted for less than 1 percent of total expenditure in the United States, between 1 and 2 percent in the United Kingdom and Germany, and around 2 percent in France. Russia is a notable exception among major nations, consistently displaying higher defense spending throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Over the past two decades, government spending has significantly increased globally, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP. However, despite the substantial costs and high rates of obsolescence related to military equipment, defense budgets have risen rather slowly, focusing primarily on personnel. In 2022, salaries and pensions made up 45 percent of military spending in the European Union, with only 22 percent allocated for equipment and 29 percent for training, supplies and maintenance.

Facts & figures: Military expenditure as a percentage of government spending, 2023

The ideal defense budget

Assessing the ideal share of defense expenditures is impossible. The only exceptions are micro-countries like Liechtenstein and Luxembourg or small and poor economies like Nepal, which stand no chance against much larger potential aggressors. In these cases, allocating a significant portion of their GDP to defense would be ineffective, and their optimal defense budget would be zero. Their best form of protection lies in the knowledge that any act of aggression would yield little benefit for the aggressor and would set off global alarm bells, making further attacks or future negotiations difficult.

Defense spending in poorer countries is justified only when they share borders with other financially challenged yet aggressive nations, often leading to prolonged conflicts. However, this does not imply that poor nations with powerful, hostile neighbors never waste resources on military expenses. One might speculate that in these instances, such expenditures have little to do with defense and more to do with establishing a sort of royal or presidential guard. This guard protects the ruler from domestic opposition and turmoil, especially when the traditional police force is unreliable.

The issue of “optimal” defense expenditure primarily concerns affluent countries that feel threatened by powerful and aggressive neighbors and can be used as springboards for future expansion. From a Western perspective, the U.S. and the European bloc currently focus on two major threats: the Russian Federation and China. Yet, the members of the Western bloc differ in two fundamental respects.

While the U.S. is committed to keeping both Russia and China in check, Europe does not consider Beijing an immediate threat and is unlikely to offer significant military support to Asian countries that come under attack. Alleged acts of Chinese sabotage are seen as a secondary concern. Moreover, while the U.S. aims to develop its defensive and offensive capabilities regardless of its allies’ contributions, Europe relies on a dual system of alliances: one among the countries within the European bloc and another between the bloc and the U.S. As such, we must look at the EU’s defense efforts from two perspectives: maintaining bloc cohesion on the one hand, and securing support from external partners on the other.

Is Europe allocating sufficient funds for defense?

At first glance, European expenditure on its defense appears adequate. In 2023, for instance, Russia’s military spending amounted to approximately $130 billion and China’s was around $315 billion. Europe spent about $390 billion. Of course, it could be argued that one dollar spent by the Russians (or the Chinese) is not the same as one dollar spent by the European NATO members. For example, the quality of personnel and equipment is likely different, the price of equipment ammunition and manpower is not the same, and there may also be variations in their willingness to engage in combat.

The figures above, however, explain the public sentiment in Western Europe following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While there is a general endorsement of the rise in military spending (an increase of 30 percent in nominal terms from 2021 to 2024), there remains a cautious reluctance among the public to support any substantial increases beyond the current level of 1.9 percent of GDP.

Interestingly, a recent poll by NATO reveals that two-thirds of people living in NATO countries believe their nation should defend another member if it is attacked. This sentiment is true in both Europe and the U.S. Additionally, many Europeans are concerned that Russia’s ambitions may extend beyond Ukraine; about 40 percent believe Russia could attack another European nation by the end of 2026. Furthermore, a two-thirds majority view the Russian military as a significant threat.

Europeans are concerned but also believe that the current military budget is adequate and that the U.S. will step in if necessary. However, both beliefs lack rock-solid foundations. For example, while most European governments and the U.S. have provided only limited military support to Ukraine, their ability to supply additional equipment and resources seems quite restricted.

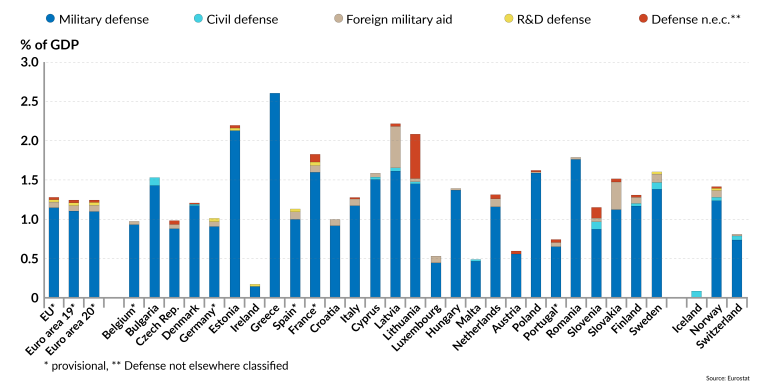

Facts & figures: General government total expenditure on defense in the EU, 2022

While Europe’s operational capacity in small-scale theaters is satisfactory, its true effectiveness – in terms of cooperation, striking power and partial transition to a war economy – has yet to be tested in serious engagements. As a matter of fact, the European Defence Agency (EDF) has highlighted “urgent gaps” in several areas that need to be addressed. For instance, according to the EDF, “Europe must strengthen its defence industrial base by ramping up production capacity, responsiveness and innovation. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has exposed the limits of EU defence industrial readiness, particularly in the ability to sustain prolonged, high-intensity operations.”

Added to this, the political foundations are becoming increasingly shaky. In the recent past, the U.S. and the UK failed to honor their commitments to guaranteeing Ukraine’s integrity against all aggressions, and President Donald Trump has made it clear that future U.S. support is by no means certain. In fact, just hours after assuming office, President Trump halted U.S. foreign development assistance for 90 days to review it and ensure it aligned with the new administration’s priorities. Under the Biden administration, Ukraine ranked at the top of this list for U.S. development aid.

Europe must spend more on its own defense to strengthen its transatlantic partnership, enhance its operational capacity and demonstrate its readiness to fight. Naturally, the perceived benefits for European countries decrease with the distance from the potential aggressor and vary based on whether the enemy’s perceived objectives are, for example, the Tsarist borders, the Molotov-Ribbentrop perimeters, the Mediterranean region or the Atlantic Ocean. In other words, each European country will evaluate the benefits of defense depending on how far the aggressor will go.

Can Europe meet Trump’s NATO defense spending goal?

President Trump has urged NATO members (especially those in Europe) to increase defense spending to 5 percent of GDP. Currently, the U.S. spends about 3.5 percent, while the EU bloc spends approximately 1.9 percent. The 5 percent goal likely aims to establish a military apparatus that would enable Western countries to take the initiative and deter aggressors from engaging in a race. However, this goal may appear unrealistic for Europe, and President Trump is likely trying to pressure the EU to define its own standards and commitments.

Such a standard could be set by countries with the strongest motivation to demonstrate their resolve against aggression. A possible rule could require all EU/NATO members to maintain a defense spending-to-GDP ratio equal to or higher than a specified percentage of European border countries – currently estimated at around 3.5 percent if Russia is considered the primary threat.

Deterrence would undoubtedly be strengthened, and the eventual early victims to aggression – the border countries – would gain a double benefit. First, tangible support from the allies would allow them to manage their own military spending and lighten the tax burden on the public. Second, these border countries would realize that every euro spent on defense would create a multiplier effect to enhance their efforts. The struggles of these relatively small nations would ultimately prove worthwhile.

Scenarios

Most likely: Europe negotiates a defense expenditure deal with the U.S.

The most likely scenario involves negotiating a defense expenditure deal with the U.S. that would meet the 2.5 percent threshold (instead of 5 percent) within the next two years, with a vague promise to raise the bar to 3 percent before the end of the decade. Within this framework, however, in the event of a confrontation with Russia, the Baltic countries, Finland and Poland would remain particularly vulnerable.

Less likely: Establishing an EU defense fund with priority access for border countries

A less likely scenario would be creating a centralized defense fund within the EU, to which the border countries would have privileged access. This fund would allow these countries to increase their military efforts – say, to the 5 percent threshold – and possibly deter potential aggressors from launching an invasion. However, in this arrangement, much of Western Europe could gain an unfair advantage, benefiting at the expense of the nations facing the most immediate threats.

Least likely: Europe’s failure to act results in defense spending spiraling out of control

The least likely scenario is that Europe fails to take proactive measures against a future global arms race, leading to large but still insufficient military expenditure. If European nations do not act to reach a defense spending-to-GDP ratio comparable to Russia’s current 6.3 percent or the necessary 5 percent for border countries in a matter of months, they may face significant repercussions.

While this scenario may seem unlikely due to weak political resolve, it could justify the EU’s operation as a federation and ensure that people living in small countries are not viewed as easy targets for aggressors.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/european-defense-expenditure/