Efforts that Failed

On a few of F. A. v. Hayek’s activities prior, during and after WWII.

Based on my conversations with F.A. von Hayek (1969-1991 and research in the Hoover Institution’s Archives (HIA), this short essay touches upon just a few of von Hayek’s many efforts to fight Nazism and to revive the tradition of the Austrian School of Economics prior, during and after WW II. An extensive version (in Italian) appeared in Un Austriaco in Italia (Rome 2012).

Of course, a political philosophy can never be based exclusively on economics

or expressed mainly in economic terms.

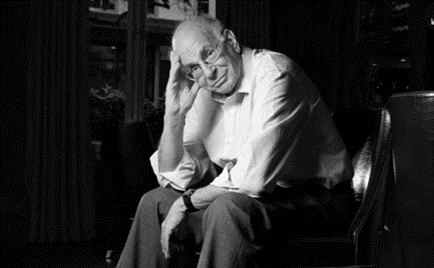

Friedrich A. von Hayek

Like countless members of his generation and social class, Friedrich A. von Hayek too had grown to manhood in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna and had expected to play a leading role in the mighty Habsburg Empire. However, in the aftermath of WW I when the K.u.K. monarchy collapsed and Austria was reduced to a small, land-locked country, his society had disappeared. Simply unprepared, the emerging new Austria could not offer the type of opportunities to which he and his contemporaries were accustomed. With a raging inflation, little hope for any decent position and a despicable racist bias creeping into a deteriorating public life, already by the early 1930s most young intellectuals, including the core members of the Austrian School of Economics, seriously began to ponder leaving the country.

And when in March 1938 the forced Anschluss made Austria a part of Hitler’s Third Reich, the damaging “Brain Drain” reached its peak. With von Hayek in London, Mises in New York, von Haberler at Harvard, or Machlup in Buffalo, and untold other scholars scattered around the world, Vienna ceased to be the stronghold for the Austrian School.

“Some Notes on Propaganda in Germany”

Even though F.A. von Hayek was among the first to leave Austria in order to accept a professorship at the London School of Economics (LSE) in the fall of 1931, he often returned to Vienna to support his family and friends. As late as April 1939 Hayek ventured for his last visit to Vienna before the outbreak of WWII and attempted to retrieve Ludwig von Mises’ precious books, manuscripts, and personal items, which Gestapo agents supported by SS troops had looted from Mises’ apartment in Vienna. Much to his disappointment Hayek’s efforts failed at the time and Mises believed his property lost forever. However, when a number of formerly secret Soviet collections, desperate for cash began to permit access, some 50 years later, two Austrian historians identified L. von Mises’ lost material, meticulously catalogued as “Fund #623-Ludwig von Mises” in a KGB archive, outside Moscow.

On his way back to London, Hayek stayed in Paris for a day to meet with Roepke, Polanyi, Rueff and von Mises and suggested there the launching of an “International Center for the Revival of Liberalism”. Due to the worsening political conditions this endeavor was short lived but served later as a model for the foundation of the Mont Pelerin Society.

Within days after Great Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany Hayek, distressed by the unfolding catastrophe not only approached the Tory radical Harold Macmillan, he also offered help to improve the BBC’s clumsy and very ineffective anti-Nazi efforts. In “Some Notes on Propaganda in Germany” Hayek showed why counter propaganda must be based on the most intimate knowledge of German psychology and conditions and described ways and means to penetrate Hitler’s grip on the media and suggested techniques to smuggle disguised anti-Nazi propaganda material into Germany. As an early by-product of his work on The Road to Serfdom, he wrote several pieces for the London based intellectual magazine Spectator and for the BBC, among them also A note on the significance of the German ‘New Order’, which seemingly inspired then Prime Minister Churchill’s many sonorous and rousing radio speeches.

Despite heavy Nazi German bombardments of London, Hayek not only tried to raise funds for Karl Popper’s appointment at LSE. Hayek also circulated among other proposals, his vision for a post war English Speaking College of Social Studies for Central Europe. Although, Hayek eventually succeeded in getting Popper to join LSE, wartime England was not the best place to lobby for the establishment of a learned institution on the war torn continent.

Among many other activities in London, in early 1944 he joined a Committee Justice for the South Tyrol which was set up by H.I.&R.H. Archduke Robert von Habsburg, George Franckenstein and several other Austrian expats. The sole purpose of this endeavor was to apply some allied pressure on Italy to consider a return of the German speaking area of South Tyrol back to Austria after the war. Hayek used his essay on The Economic Position of the South Tyrol and several other shorter pieces also to promote his idea of an independent private university in Bozen (Bolzano) to counter the forceful Italianization of South Tyrol. Although, the committee did not succeed and thus suspended its operations soon after the war, Hayek kept himself engaged in South Tyrolian matters until well into the 1980s.

With the war still raging, in the spring of 1945 Hayek started to tour the US to promote his book The Road to Serfdom. Even John Maynard Keynes called it “a grand book” and the excellent condensed version appeared in the Reader’s Digest, which made Hayek a celebrity upon arrival in the US. A small but highly polemic cartoon booklet (Thought Starter #118) of the Road to Serfdom issued by GM, appeared in Detroit. Hayek used his status and wherever he lectured in the U.S., he pushed hard to disseminate his idea of an International Academy for Social Philosophy in Vienna.

Back in London, in July 1945 Hayek met with Anthony Fisher, a former Royal Air Force pilot and persuaded him to establish a private research organization dedicated to the understanding of the fundamental institutions of free markets and a society of free people. The London based IEA, Institute of Economic Affairs was founded about 10 years later and is still considered a model for most think tank ventures of this kind.

“The Historians and the Future of Europe”

Hayek’s visionary talk in Cambridge on “The Historians and the Future of Europe” in which he argued that the future of Europe will be largely decided by what will happen in Germany already pointed toward his important plans. As early as September 1945, by some means he obtained permissions for his travels to Paris and Zurich and met there among others J. Rueff, W. Roepke, and the influential Swiss businessman, A. Hunold. Wary about the fast communist expansion in Central Europe, Hayek’s plan was to raise substantial private funds for a conference of like-minded thinkers in Switzerland. He revised his 1938 draft and circulated his new Memorandum on the Proposed Foundation of an International Academy for Political Philosophy, tentatively called ‘Acton-Tocqueville Society’. On April 1, 1947 Hayek was able to welcome 39 isolated liberal (European sense) scholars from 10 countries at Mont Pelerin, above Vevey in Switzerland. This gathering initiated the foundation of the international Mont Pelerin Society.

As a result of the final collapse of Hitler’s Third Reich, Austria and Vienna were divided into four military occupation zones. Thus, Vienna like Berlin became an isolated island in the middle of a large Soviet controlled area. And yet, in early 1946 against all odds Hayek managed to obtain a permit for travels into the Soviet occupied part of ruined Vienna visiting surviving family and friends. Deeply shocked by the unbearable conditions there, he wrote a scathing essay for the popular press in London. In his Austria: Advance Post in Europe he accused the Allies of treating Austria much worse than Italy or any of the other countries which joined Germany voluntarily and demanded an immediate end to the Allied occupation, and a joint commission of economic advisors. About 10 months later he was even more drawn to the plight of the deprived scholars and students who kept returning from the war as released POWs or from liberated camps. After 8 years of intellectual isolation and in a shattered academic environment there was not much hope for them to link up with the Western academic world. Jointly with George Franckenstein, Fritz Saxl and a number of other fellow emigrants he founded the Austrian Book Committee in order to draw the public’s attention to the urgent needs of scholars and students in Austria, particularly in Vienna, who receive no adequate teaching but who might well someday continue the Viennese tradition if they were given an opportunity to acquaint themselves with the state of modern economics. He availed himself as chair and started to collect books and money to help the Austrian libraries with works on the Humanities and the Social Sciences published in England since 1938 and to arrange their transport to the Austrian National Library in Vienna. With important figures such as Lord Beveridge or T.S. Elliot among its sponsors, not before long the committee had collected some 2,500 books, and in early 1948 Hayek was able to supervise their distribution in Vienna. A small first batch of books and journals was received there with much gratitude and joy. However, the widespread appalling inefficiency of the Austrian state bureaucracy and its reprehensible political bias hampered Hayek’s further efforts and he suggested terminating the committee’s operations in July 1948. The lack of English books and leading periodicals bearing on the humanities and the social sciences was felt in Austria until well into the 1970s.

Despite his frustration, Hayek did not yield and began to work on his idea to bring back together some of his old Austrian colleagues and friends in Vienna. With seed money from the Rockefeller Foundation, but predominantly financed by keen and dedicated Austrian entrepreneurs (among them J. Meinl), he was able to invite G. von Haberler, F. Machlup, O. Morgenstern, J. H. von Fuerth, M. St. Browne, and L. von Mises to teach a kind of summer school in Vienna between late June and the end of July 1948. Among the 26 attentive students gathered on the premises of the Julius Meinl Company were Max Count Thurn, J. Meinl, A. Mahr, or Reinhard Kamitz (who later became Austria’s Federal Minister of Finance and was instrumental for the ‘Austrian economic miracle’ of the 1950s and early 60s. Although, much appreciated by many students and entrepreneurs, his initiative to revive the Austrian School in Vienna could not be repeated, most likely due to a strong political resistance and politically induced lack of funding. Hayek’s lectures on The Political Consequences of Central Planning at the invitation of the Federation of Austrian private Industrialists, severely aggravated the powerful Socialist Party (SPÖ) and the Soviet backed Communists (KPÖ) and set off a public uproar. The German version of The Road to Serfdom (published in Switzerland) thus became available in Austria only after 1949.

At the invitation of Karl Brunner, (CH), on his way back to London by the end of August 1948, Hayek spend a few days in the small Swiss village Einsiedeln for discussions and seminars with several “Swiss Austrians” among them W.A. Jöhr, E. Küng, F.A. Lutz, the Italian A. Amonn, and his Austrian fellow expats Gottfried von Haberler and Oskar Morgenstern.

“Memorandum on the Condition and Needs of the University of Vienna”

Quite surprising for most of his friends, for family reasons Hayek left the LSE in December 1949, spent the spring at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, and joined a galaxy of extraordinary minds at the University of Chicago in the fall of 1950. Although, traveling to the continent thus became much more complex, expensive and time consuming, Hayek did not rest, eagerly kept his contacts and continued to take his summer vacations in the Tyrolean Alps.

After Austria’s negotiations to end the allied occupation gradually started to produce results, Hayek skillfully utilized both, the impending neutralization of Austria and the traditions of Vienna for lobbying in favor of the foundation of an Austrian Institute, Inc. in New York in late 1954. In a confidential Memorandum on the Condition and Needs of the University of Vienna he described the University of Vienna, his Alma Mater as “one of the great centers of science and scholarship which during the last 3 or 4 generations has given the world perhaps as many original thinkers of the first rank as any other. There is still a spark glimmering, there is still left an atmosphere and a number of first class men that should make it possible to revive the old tradition”. Even though an “American Committee for Vienna University” with some prominent US personalities on its board, actively supported this endeavor it seems that once again the Austrian local academic and political bias in Vienna effectively mired his efforts. However, Hayek kept at it and tried to circumnavigate these formally induced partisan impediments by approaching several independent US foundations with a new “Proposal for the Creation of an Institute of Advanced Human Studies in Vienna, Austria” (similar to his draft of 1943). Keen to strengthen Vienna as a main intellectual fort at the boundaries of the West he proposed a private and autonomous “Central European College” and tried at the same time to sway Karl R. Popper or the art historian Ernst Gombrich among others toward a return to Austria. To this end, Hayek had a few promising meetings with government officials in Vienna in June 1959. The Austrian expatriates, P. Lazarsfeld and O. Morgenstern with a major contribution by the Ford Foundation, however founded the “Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna” in 1963. Although, Hayek was among its first scholars in residence, by the prevailing Zeitgeist however he became somewhat intellectually isolated. Over the years, the institute has changed its earlier free market approach and has developed into a chiefly quantitative research institution.

While teaching in Vienna, Hayek initiated yet another endeavor to revitalize the tradition of the Austrian School. With F. Andreen, Max Count Thurn and R. Kamitz on its board, in 1963 Hayek became instrumental for the foundation of the “International Freedom Academy”, a small privately funded think tank in Vienna. Although, INFRA had a very promising start, it also ceased its operations after 3 years and eventually moved to South Africa.

A few years after Hayek accepted a professorship at the University of Salzburg, he tried one last time, despite his advanced age and relatively poor health. Shortly after Ludwig von Mises died in October 1973 in New York, Hayek against many odds worked very hard to raise private and public funds for the acquisition of L. von Mises’ library in order to merge it with his own unique collection in Salzburg. With thousands of offprints and countless rare books, such arrangement would have produced by far the most complete library ever dedicated to the Austrian School of Economics. However, the prevailing Zeitgeist, the political bias, and conceivably even a lack of an entrepreneurial resolve, have also caused his last ambitious endeavor very sadly to fail.

Throughout the years immediately following WW II and during the 1950s, Austria successfully managed her economic reconstruction and political potential by drawing from a large pool of executive talents and inspiring public figures, which survived terror, war, and concentration camps. And yet, it somehow remains a puzzle why the Austrian authorities, let alone the interested public did not proceed likewise by inviting back some of the greatest minds of our times to help rejuvenate her rich academic traditions.