As the U.S. and China clash on trade, one deal

offers a third way

While the world appears increasingly fractured between the complex American and Chinese spheres of influence, countries that have not taken sides seem to be stuck with an impossible choice. Yet the almost-forgotten Comprehensive and Progressive Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP), a multilateral free trade agreement significantly lowering tariffs and barriers among some G7 and Global Majority countries, could help create a third path.

The challenges to its wider adoption, though, are formidable.

The logic of integration

Between the post-World War II Bretton Woods system and the global financial crisis of 2008, world trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) had steadily increased (in absolute terms). This was thanks to efforts in trade and investment liberalization, especially through the multilateralism of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), but also through bilateral or regional free trade agreements.

As firms became multinational at an accelerated pace, global value chains became more integrated. This globalization process, based on countries’ and firms’ competitive advantages, led to increased efficiency and sustained economic growth on a global level, bringing development for poorer nations and lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty.

Freer trade reduces costs for producers, thanks to the more diverse sourcing and economies of scale provided by a larger market. It also offers consumers lower prices and a wider selection. Overall, societal welfare improves. Communist China “going capitalist” within the WTO in 2001 seemed to have been the peak of the process. This period, often referred to as hyper-globalization, saw the ratio of the world’s trade compared to its gross domestic product (GDP) rise from less than a third after the fall of the Berlin Wall to half in 2008. Geopolitical lines had apparently been erased, largely due to initiatives from the United States.

Cracks and geoeconomic fragmentation

That period of sustained economic expansion continued until the financial crisis in the U.S. and Europe and the subsequent Great Recession, after which trade growth stagnated somewhat. A few years later, protectionism began to take hold. Some countries implemented higher tariffs, non-tariff barriers and export restrictions, while pushing assertive industrial policy and strategic autonomy. The pandemic, followed by Russia’s war on Ukraine, accelerated the end of the era of expansion. U.S. weaponization of the dollar, as well as U.S. and European Union sanctions (especially against Russia) increased the need of targeted countries – and others – for an alternative financial system (hence BRICS and its initiatives), challenging the Western status quo.

China, especially under President Xi Jinping, has chafed at U.S.-centered globalization. However, the country benefitted immensely from its inclusion in the WTO, drawing value chain links to itself that previously were more fragmented and internationalized. Since then, the U.S. has viewed China’s rise with deepening concern, with its technological catch-up amid American deindustrialization (the famous “China shock”).

This has led to growing U.S.-China tensions, notably under President Donald Trump’s first term and even more so in his second. The American president wants to scrap the WTO’s rules-based order and is focusing on bilateral trade deals, using U.S. economic and military bargaining power, even with allies. The world’s economic fracturing has begun to intensify.

Such reordering would not mean deglobalization – no drop in overall trade volumes – but rather a shift in the global economic and financial architecture along geopolitical rivalries.

Geopolitical shocks – and therefore, risk – have blunted global trade and investment. This trend has given firms an incentive to re-shore or friend-shore parts of their supply chains (to Southeast Asia or Mexico for U.S. firms, for example). This has accentuated the potential for geoeconomic fragmentation: the reshuffling of world trade and geographical structures of investment between rival geopolitical blocs. Such reordering would not mean deglobalization – no drop in overall trade volumes – but rather a shift in the global economic and financial architecture along geopolitical rivalries.

According to a study by the Bank of Finland, while the U.S. has reduced its trade with China, the added value from China in U.S. manufacturing between 2018 and 2024 has remained stable and has even increased in EU manufacturing – a reminder of the complexities of decoupling. Despite this, after Mr. Trump’s abrupt policy shifts this year, the emergence of a new geoeconomic cold war is undeniable. While this fragmentation could be costly and threaten the prospects of a more open world through freer trade, it could also lead to kinetic war.

Adapting to a post-WTO world

The WTO has clearly failed since the Doha round – the organization’s efforts since the start of this century to adapt its rules to the needs of less-developed nations – and even more so since 2016, when the U.S began blocking nominations for WTO appellate judges. Observers see both Washington and Beijing as unwilling to adhere to the rules-based trade order and increasingly as opposing poles of attraction. This is the context in which some are reconsidering the potential of a particular Indo-Pacific project to revive rules-based, multilateral free trade: the CPTPP.

Between 2005 and February 2016, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), promoting free trade, was signed by 12 countries: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam and the U.S. Then President Barack Obama saw the agreement as a way to counter China’s rising economic influence. However, not even a year after the U.S. signed onto the partnership and before congressional ratification, President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the project.

The 11 remaining countries then negotiated a new agreement, the CPTPP, which entered into force in 2018. Since then (and due to the U.S.-China trade war), the multilateral grouping has become more attractive, even for countries far from the Pacific. In December 2024, it expanded with the accession of the United Kingdom, bringing the CPTPP’s combined economic value to 15 percent of global GDP. Costa Rica, Ecuador, Indonesia, Taiwan, Ukraine and Uruguay have also applied to join. Leaders in both South Korea and the EU have expressed interest in joining or cooperating with the CPTPP, which would significantly expand the trade zone’s economic heft.

China’s application, first submitted in 2021, has been blocked several times so far.

The CPTPP, under Japan’s leadership, has been very much inspired by the initial vision of the TPP: freer, fairer trade based on the transparency of rules enabling broader and deeper cooperation. It eliminates or drastically reduces tariffs for nearly 100 percent of goods traded among members (with some exceptions, such as to protect Japanese rice or Canadian dairy products). Services such as finance, investment and transportation are included. State subsidies are constrained.

The partnership also promotes shared standards for intellectual property, environmental and labor standards, e-commerce and data. Its vision is to secure and stabilize supply chains around shared economic and civilizational values, while countering China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the more recent Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in the Indo-Pacific.

An alternative bloc

The CPTPP could enlarge even further. In June, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen suggested working with the CPTPP as a way of “redesigning the WTO.” The U.S., China, India and others have prevented WTO reform, which has brought fatigue and frustration with the organization.

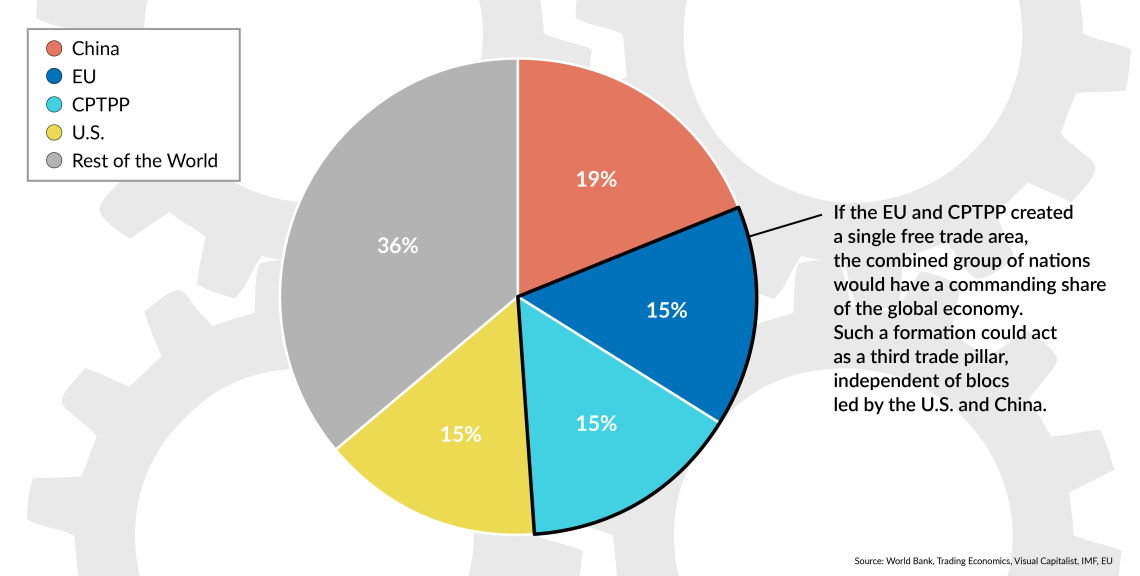

Facts & figures: Portions of global GDP (PPP adjusted, 2024)

Denmark, which is currently presiding over the EU Council for six months, has also said it is open to European cooperation with the CPTPP. The prime ministers of both New Zealand and Singapore have likewise suggested similar moves for their countries. While referring to the CPTPP in his keynote speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue summit in Singapore in May, French President Emmanuel Macron talked about a “third way.” Clearly the CPTPP combined with the EU could offer a third global trading bloc, an alternative to the emerging U.S.-led and China-led blocs.

While the EU-CPTPP talks are only just beginning, the snail-paced, bureaucratic EU could now act with the greater urgency that is necessary largely due to Mr. Trump’s actions. Even without the EU, the CPTPP already represents nearly 600 million people, accounts for 15 percent of global GDP and 15 percent of global trade – and is set to grow. The inclusion of the EU would add 450 million people and raise both these percentages to 30 percent.

The CPTPP with the addition of Europe would be the largest global trading bloc, giving its members greater soft power. The EU already has trade and investment agreements with most countries of the CPTPP (save Brunei and Australia). Additionally, the EU has an economic partnership agreement with Japan, the leading country in CPTPP, and the two in July launched a Competitiveness Alliance bolstering trade and security.

Scenarios

Unlikely in the near term: EU accession to the CPTPP

In the short term, European accession to the CTPP faces substantial obstacles. The EU’s regulatory activism presents a non-tariff barrier, especially in terms of data protection, which does not align well with the CPTPP. The same goes for the EU’s tradition of agricultural protectionism.

Another factor is European popular backlash, from both the right and the left, against such agreements, as demonstrated when Brussels recently concluded the EU-Mercosur free trade deal. What is more, a large part of the European bloc is politically unstable, with traditionally protectionist far-right parties gaining sway, such as the National Rally in France or the AfD in Germany. On the left, ecological activists could criticize the deal for promoting supposedly climate-damaging freer trade.

Externally, an isolationist but assertive Trump administration might resent an EU-CPTPP deal as overly bold and a way for Europeans to outplay and exclude the U.S. in the short term. The July EU-U.S. deal was probably not the best deal the EU could get; an angry and erratic Mr. Trump could alter it further, using threats to pull U.S. support for NATO as a lever to keep Europe aligned with American interests.

Possible in the medium term: CPTPP transatlantic expansion

In the mid-term though, the need for growth and new opportunities in a rapidly deindustrializing Europe and U.S., together with a change of heart in America, could alter the situation significantly.

Depending on the effects of Mr. Trump’s protectionist policies on the U.S. economy – the latest figures are not auspicious – America could once more become a proponent of free trade, maybe with a Democrat (or a genuine libertarian conservative) presidency in 2029. After all, in 2022, then President Joe Biden tried to salvage a post-TPP security agreement with the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, although it was not a trade agreement (and frankly neither very exciting nor promising). So, in the medium term, the odds for a significant expansion of the CPTPP are not entirely unlikely.

Unlikely: China joins the CPTPP

An even less likely possibility would be Chinese accession to the CPTPP, especially if it happened before the EU were to join the partnership. This has already been prevented four times, notably because of an Australian veto against what was perceived as Beijing’s coercive trade practices and a lack of any compliance mechanism. Indeed, Beijing’s subsidies to state-owned enterprises, intellectual property rights protection still perceived as weaker, exchange-rate and export-price manipulation, data control and weak labor rights do not align with CPTPP rules. And to some degree, the CPTPP is a project to counter state-capitalist, communist China.

Beijing claims that it has now entered a second stage in its renewed development and that it has tested CPTPP regulations domestically in free trade pilot zones. Besides, China is party to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), in which seven CPTPP economies also partner, notably Australia, Japan and New Zealand. The RCEP is a free trade agreement, with a narrower scope – even so, it would help CPTPP-China negotiations. However, the required reforms would be extensive and run against the current Chinese approach.

A successful accession would certainly mean Chinese hegemony, creating a paradox of an anti-China project helping China’s rise, directly hitting the credibility of the CPTPP. It is doubtful whether the U.S. would let that happen. Washington would likely pressure Japan, Australia, the EU and all countries that would dare to deal with its archrival, both in the short and medium term. In both cases, the project would certainly implode.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/cptpp-trade-partnership/