Europe’s brain drain:

Can the EU compete for talent?

Europe faces a growing challenge that cannot be solved easily: the loss of human capital. As global competition for skilled labor intensifies, the European Union is struggling to retain its best minds and attract new ones. This “brain drain” is not a new phenomenon, but it is becoming increasingly acute, structural and geopolitically relevant.

In an aging continent with shrinking working-age populations, talent has become the scarcest and most strategic resource. The EU still educates many of the world’s brightest students and researchers, yet many of them go on to build their careers elsewhere. Meanwhile, Europe’s ability to attract foreign professionals remains patchy and bureaucratically constrained. Across sectors, from artificial intelligence and life sciences to engineering and entrepreneurship, the continent risks falling behind not for lack of ideas, but for lack of people to implement them.

The EU status quo: Migration patterns and talent flows

Europe is not isolated from global migration flows. In fact, EU member states continue to attract large numbers of migrants every year, both from within the bloc and from abroad. Yet a closer look at the data reveals a striking pattern: While the EU receives many migrants, it simultaneously loses a disproportionate share of its own highly skilled citizens. Moreover, an overproportionate share of first-generation migrants into the EU have low educational attainment levels. The result is a net migration flow where quantity and quality are misaligned, where demographic gains do not translate into economic vitality or innovation.

According to Eurostat, roughly 4.3 million people migrated to the EU from non-EU countries in 2023, while 1.5 million people left the bloc. This corresponds to a net population gain of 2.8 million people. Intra-EU mobility is also significant, with approximately 1.5 million people moving between EU member states annually. While such internal mobility reflects the freedoms of the single market, it also leads to regional imbalances, as countries in Eastern and Southern Europe see their best-trained citizens relocate to wealthier northern states.

On the immigration side, many third-country nationals come to Europe for work or study, but the composition of skills is mixed. The EU Blue Card scheme was intended to facilitate high-skilled immigration, yet its uptake remains modest compared to Canada or Australia’s fast-track systems. Many international students educated in Europe ultimately leave after graduation, citing bureaucratic barriers and limited career prospects as primary reasons.

On the emigration side, Europe continues to see an exodus of researchers, engineers, medical professionals and entrepreneurs to the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and increasingly to Asia. In some cases, the EU not only trains this talent, it subsidizes it with tax-payer money – only to see the benefits accrue elsewhere.

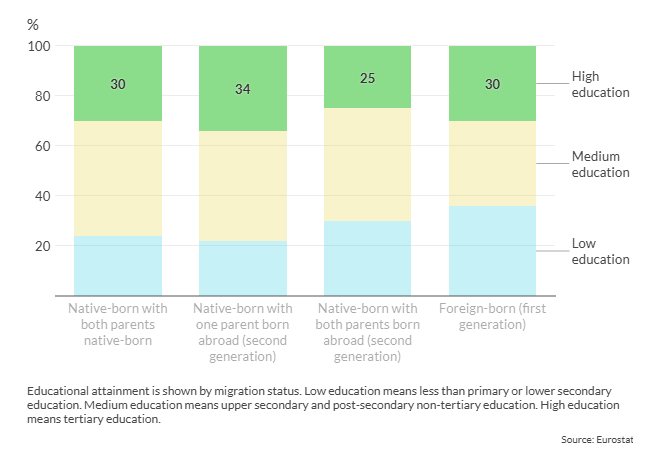

Facts & figures: EU 27 – Distribution of educational attainment by migration status in 2024

This dual pattern of brain drain and attraction of low-skilled immigrants underscores the need for a more strategic and competitive approach to human capital, the primary driver of economic development over the long term. Economies that can neither attract highly skilled immigrants nor prevent the best-trained citizens from leaving will face serious losses in terms of economic growth and prosperity.

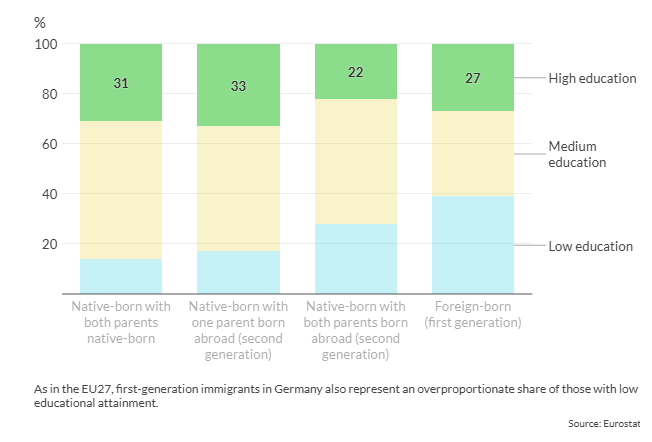

Facts & figures: Germany – Distribution of educational attainment by migration status in 2024

This educational imbalance can be seen both at the EU level and in its largest economy, Germany. In Germany, 39 percent of first-generation immigrants have a low level of education, compared to only 14 percent of native-born citizens with both parents native-born. The proportion of highly educated first-generation immigrants is slightly smaller than the proportion of highly educated native-born citizens with both parents native-born (31 percent versus 27 percent). On the overall EU27 level, the proportion of highly educated first-generation immigrants reaches almost 30 percent and is close to the corresponding proportion among native-born citizens with both parents native-born. However, there is also a clear overrepresentation of immigrants with low educational attainment (24 percent versus 36 percent).

There is another interesting feature in the data: Both in Germany and at the EU27 level, we observe the highest proportion of highly educated individuals (34 percent in the EU and 33 percent in Germany) among native-born citizens with one parent native-born and the other foreign-born. If mixed parentage is taken as a proxy for successful integration, the data suggests that well-integrated immigrants contribute positively to educational outcomes. This is precisely the type of migration Europe should foster. At the moment, it is overshadowed by first-generation immigrants with low educational attainment. In both Germany and the EU overall, first-generation immigrants outnumber mixed-parentage native-born citizens by roughly three to one. In Germany, the numbers are 14 million versus 4.9 million; at the EU level, 48.9 million versus 14.8 million.

This mismatch between the EU’s talent needs and its migration outcomes reflects deeper structural factors – both internal and external – that shape Europe’s position in the global competition for brains.

Pull factors: Why Europe loses the global talent competition

Europe faces stiff competition from countries that have developed deliberate, targeted strategies to attract and retain highly skilled workers. Such countries offer not only higher wages and better career prospects, but also clearer paths to residency, greater academic freedom and a culture of meritocratic advancement. Compared to these environments, Europe can appear rigid, bureaucratic and unattractive to mobile professionals.

The U.S. continues to be the top destination for many of Europe’s brightest minds, despite recent disruptions by the second Trump administration. It combines world-leading universities, dynamic labor markets and a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem backed by ample venture capital. Research and development clusters in the greater areas of Boston, San Francisco and Austin have become magnets for European scientists, engineers and start-up founders. Academic and scientific freedom are widely perceived as greater in these areas than in many European institutions, particularly for young researchers facing stiff and hierarchical structures or limited funding opportunities at home.

These [other] countries treat high-skilled immigration as a form of industrial policy, not merely a labor market issue. Europe, by comparison … treats immigration more as a humanitarian issue.

Canada and Australia have also emerged as highly competitive destinations. Both countries operate well-publicized, point-based immigration systems that prioritize skills, qualifications and labor market needs. Their visa procedures are comparatively fast and transparent, and both offer post-study work permits and pathways to permanent residency. Canada’s Global Talent Stream, for instance, allows tech firms to hire foreign professionals with a two-week processing time. In contrast, European systems are often fragmented, slow and unpredictable.

The UK, despite Brexit, has repositioned itself as a global magnet for talent by launching the “High Potential Individual” visa and other schemes targeting graduates from top global universities. Singapore and the United Arab Emirates are also courting tech professionals and scientists with tax incentives, English-speaking environments and streamlined work permits.

These countries treat high-skilled immigration as a form of industrial policy, not merely a labor market issue. Europe, by comparison, still lacks a coordinated approach to compete in this arena. It treats immigration more as a humanitarian issue than anything else. While the EU’s Blue Card scheme was a step in the right direction, its limited uptake and uneven national implementation have prevented it from becoming a credible competitor to more agile systems.

Unless Europe adapts to the new competitive landscape, its top talent will continue to follow the global pull of opportunity elsewhere.

Push factors: Taxation, regulation and bureaucracy

Europe’s difficulties in retaining and attracting talent are not only the result of stronger offers from abroad, but also of self-imposed obstacles. High taxes, heavy regulation and bureaucratic inertia continue to weigh down Europe’s competitiveness in the global market for skilled labor.

In many EU countries, high marginal tax rates on top earners and entrepreneurs act as a deterrent to talent. While progressive taxation is often justified on equity grounds, the effective burden on high-skilled individuals is significantly greater than in key competitor economies. Countries such as the U.S., Switzerland or Singapore offer more attractive net income prospects, especially for mobile professionals in tech, finance and academia.

Regulatory complexity adds a second layer of friction. Labor laws, social security rules and recognition of qualifications vary widely across member states. Starting a business or hiring skilled workers from abroad often involves navigating overlapping national and EU-level requirements. For foreign professionals and investors, the system can appear opaque and discouraging.

Underlying both problems is a broader issue of bureaucratic inertia. Administrative procedures for visas, residence permits, work authorizations and academic hiring remain slow and fragmented. In sectors where speed and flexibility are essential, such as tech or research, Europe often loses out simply because it cannot act fast enough. Unless these internal barriers are addressed, Europe will continue to trail more agile competitors in the global contest for the brightest minds.

Scenarios

The question facing Europe is no longer whether it is in a global competition for talent, but whether it can compete at all. Based on current trends and policy responses, three scenarios emerge for the next decade.

Somewhat likely: Locked in, left out

In this scenario, protectionist instincts prevail. Immigration policy remains fragmented and slow, with limited reform of the EU Blue Card and persistent barriers to third-country professionals. High taxes and regulatory burdens remain largely untouched, while national debates on migration become increasingly politicized. Intra-EU mobility continues, but the bloc loses global attractiveness. Europe remains a training ground for others, with top graduates, researchers and entrepreneurs steadily flowing to more dynamic economies. Innovation gaps widen, and regional disparities deepen. The probability of this scenario is 30 percent.

Likely: Selective openness

Europe undertakes modest but targeted reforms. The Blue Card scheme is streamlined and expanded, and selected member states (such as Germany, the Netherlands and Estonia) implement faster visa and residence procedures for high-skilled workers. Tax incentives for foreign professionals and simplified start-up regulations appear in a handful of jurisdictions. Academic institutions gain greater autonomy to recruit globally.

However, progress is uneven. The EU remains competitive in certain sectors and cities but fails to project a coherent global brand for talent. The brain drain slows, but does not reverse. The probability of this scenario is 50 percent.

Unlikely: Talent-driven strategy

Europe adopts a coordinated and ambitious approach, treating talent attraction as a cornerstone of economic and geopolitical strategy. A unified EU-wide talent visa emerges, coupled with reduced administrative burdens and tax incentives for top performers. Pan-European recognition of professional qualifications becomes the norm. Academic careers are modernized, start-up ecosystems revitalized and international students actively retained. Europe transforms from a fragmented labor market into a magnet for global talent. The continent shifts from net brain drain to net brain gain – and regains ground in global innovation. The probability of this scenario is 20 percent.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/europe-brain-drain/