The evidence suggests that to some extent, both sides were correct. Over the past three years, the growth rate in real gross domestic product (GDP) accelerated at first by about 30 percent in the UK and 21 percent in the EU (during the post-Covid-19 economic restart), but it flattened in both cases in the last three quarters. According to an April 2023 report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), GDP over the next five years should be more or less stagnant in the UK and the EU. The Leavers had been right in maintaining that Brexit would not bring about an economic catastrophe for the UK. The Remainers argued that leaving the EU alone would not make the dream of a supercharged Britain come true.

Brexit, three years later

The British public has grown disappointed with Brexit’s consequences. Given the disingenuous national debate leading up to it, the fiasco is not a big surprise.

Brexit formally came into effect in February 2020, some 27 years after the United Kingdom entered the European Communities (the European Union’s predecessor) and less than four years after the referendum gave a slight majority (51.9 percent) to the Leavers, a figure that drops to 37.4 percent if one considers all registered voters.

Brexit happened because British voters had three significant concerns. They did not want to join the eurozone and give up monetary independence, but at the same time, they feared that staying out of the euro area would have weakened their political weight in Brussels and possibly made them vulnerable to undesirable waves of banking regulation coming from the European Central Bank (ECB).

They were also increasingly worried about the inner dynamic characterizing Brussels’ institutions, that is, the transformation of an original European project devoted to free trade, free capital and labor movements into a blueprint for a technocratic planning “superstate” managed by an ever-more powerful and expensive bureaucracy (Britain was a net contributor to the EU budget).

Last but not least, the British public was stirred by the notion that Brussels’ policies could swamp the UK with an unrestricted flood of immigrants from all over the world.

Magical thinking, misplaced hopes

By contrast, the main argument put forth by the Remainers had to do with economics. They believed that looser ties with Europe would lead to lower trade volumes and investment and a possibly weaker status for London in global politics and finance. The Remainers thought the UK would be unable to compensate for the lost benefits of tighter European economic integration with closer ties with the United States, China and the former Commonwealth countries. Lower economic growth and a lesser geopolitical role would have followed, their argument went.

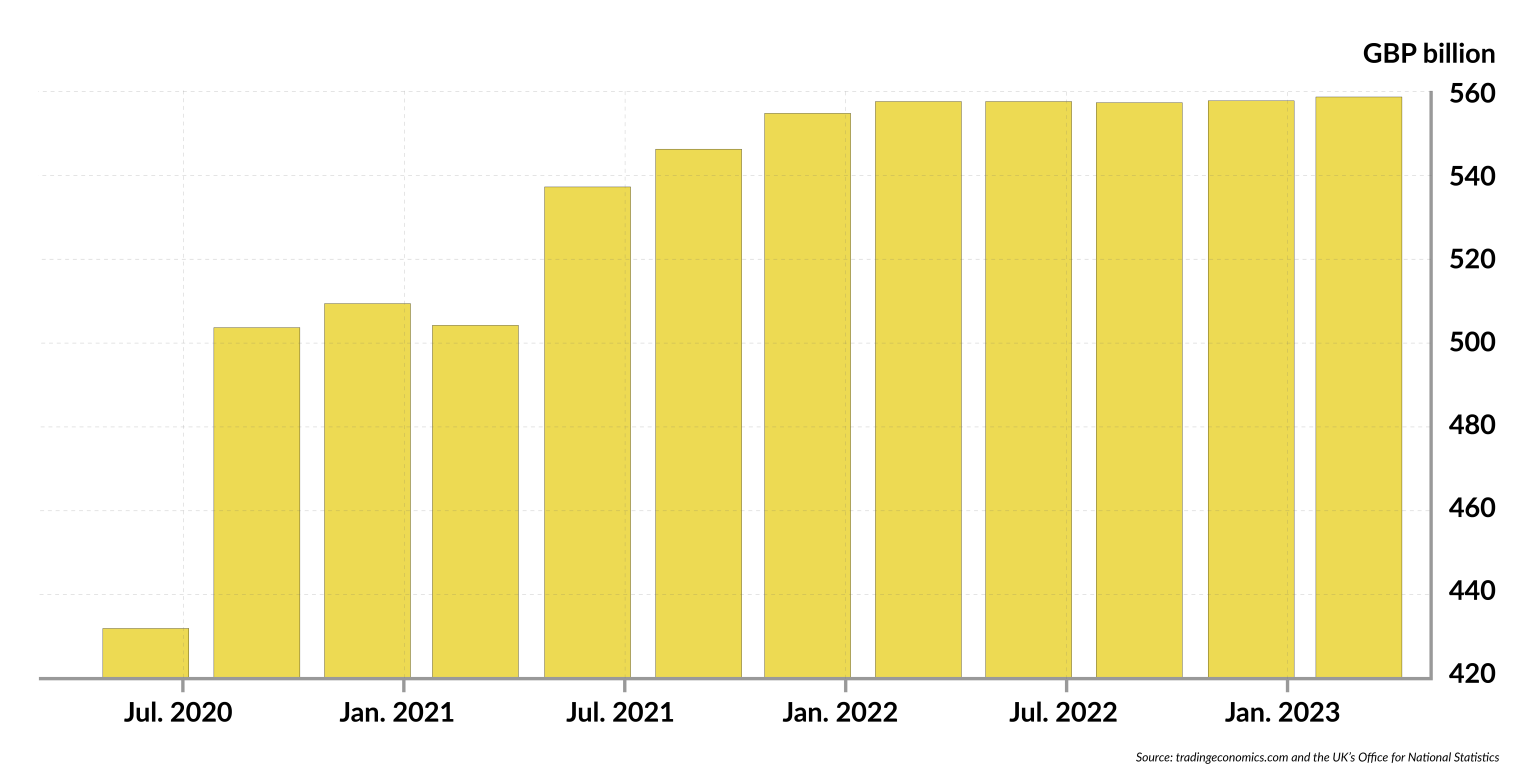

Stagnant U.K. economy

The policymaking fiascos

Similar comments apply to monetary policy. Since Brexit, the Bank of England (BoE) and the ECB have both engaged in extensive interest-rate manipulations and unorthodox monetary policies, while doing a lamentable job of monitoring the banking sectors. If one is to judge from the current UK rate of inflation (10.1 percent in March), the BoE has performed worse than the ECB. Brexit has made no positive policy impact, and the banking industry remains fragile on both sides of the English Channel.

The size of government has been a significant factor in the UK case.

Regarding the quality of policymaking, valuable information comes from the Index of Economic Freedom compiled by the Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal. Between 2020 and 2023, the UK’s score dropped 11.85 percent, and its economy is now considered “moderately free” (it used to be “mostly free”). For comparison, during the past three years, the index for Germany (a mostly free economy) has remained nearly constant, while the index for France (moderately free) declined 3.6 percent.

Facts & figures

The overgrown, overbearing government

Among the particulars that contribute to the index’s final score for each country, the size of government has been a significant factor in the UK case. Its debt-to-GDP ratio is above 100 percent, public expenditure keeps rising (now above 46 percent of GDP) and the predicted budget deficit for the fiscal year 2022-23 is a worrying 6 percent (the EU figure is about 3.5 percent).

Just as the Remainers feared, Brexit has not improved the quality of policymaking, has failed to strengthen the condition of the UK’s public finances and has had a negligible impact on productivity. At the end of last year, the country’s productivity was less than 2 percent higher than in 2018 and 2019 (the EU figure was similar).

Brexit could have been a winning move instead of a fiasco had it led to a better economic situation than under the EU framework. Instead, all remained business as usual. The Liz Truss government briefly tried to alter the picture but failed miserably. Critics bemoaned Ms. Truss’s failure to explain how she would balance the budget with significantly lower tax revenues. However, most British were unwilling to accept lighter government and lower public expenditure. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, a fervent Brexit supporter but not quite a free-market aficionado, belongs to the business-as-usual camp, which earned him his current position.

No going back to the EU fold

Mr. Sunak’s approach is a good guide to figuring out the future of the British economy. He is not the standard bearer of an economic school of thought. Like most of his counterparts in Europe, is aware that the national economy is in trouble, readily describes the symptoms (deficient education, poor productivity and low investments), and concludes that the solution should come from better government policies.

Not surprisingly, “less government” is not part of the prime minister’s program. Instead, his strategy seems to be: do nothing, increase public expenditure if you can and keep your fingers crossed.

Brexit may have opened a window of opportunity, but the British have been unwilling to exploit it.

This attitude is not paying off in electoral terms: opinion polls show that 58 percent of the British believe economic conditions will deteriorate over the next 12 months. Moreover, support for the Conservative Party did recover from the Truss disaster (September-October 2022) but is still behind the pre-Truss months and far behind 2021 levels.

Only 15 percent of the British are happy about how the government runs the economy. Prime Minister Sunak’s popularity is also disappointing: 45 percent of British people have an unfavorable view of him (29 percent have a favorable view).

Brexit may have opened a window of opportunity, but the British have been unwilling to exploit it, which turned the brave policy move into a fiasco. It seems many thought that the very word – Brexit – would do the magic. Indeed, if elections took place today, the post-Brexit governments and Prime Minister Sunak would be the losers.

Both the Leavers and the Remainers were therefore mistaken. The quality of Brussels’ policymaking is questionable, but merely replacing the EU technocrats with the British civil service has not changed things. An attempt by the cabinet of Ms. Truss to see things differently was terminated by the country’s political establishment with brutal speed, almost unanimously.

Scenarios

Nowadays, the British public seems to regret Brexit. According to a poll conducted by Focaldata and UnHerd at the end of 2022, 54 percent either “strongly” or “mildly” agreed that “Britain was wrong to leave the EU.” In late February 2023, a YouGov poll indicated that 53 percent of the population believed the UK was wrong to leave, with 32 percent still supporting that call. Yet, the UK is unlikely to rejoin the EU.

High price, little gain

The UK’s pro-EU sentiments are not driven today by a desire to be part of a large club where economic growth is sluggish and centralized policymaking grows by the day (consider legislation over climate change and the energy transition). The status quo will likely prevail once the British public learns what it would take to rejoin the EU again (including, likely, entering the eurozone).

Another important reason is that Brussels is probably not eager to discuss remarrying the demanding (and possibly disloyal) British partner. Moreover, it would create new tensions with candidate countries standing in line and cause unrest among those EU employees who would need to go home to make room for the newcomers from across the Channel. Having a larger budget and more geopolitical weight may not be enough to make the EU technocrats smile.

The least-resistance path

Brexit presented a unique opportunity for those not just running away from the EU, but eager to energize the UK through restoring economic freedom – i.e., massive deregulation, unilateral free trade and much lower government expenditure – to show a stagnant Europe the way. The experiment ended in a fiasco because most people in the UK were blaming the EU for their deficiencies and had found a convenient scapegoat for it.

The window of opportunity is still there, but it is doubtful that the present or coming UK governments will seize it. As a result, it will be business as usual, and the UK economy will remain as mediocre as in most of Europe.

Original material was published by GIS: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/brexit/