Tectonic shifts in AI-powered banking

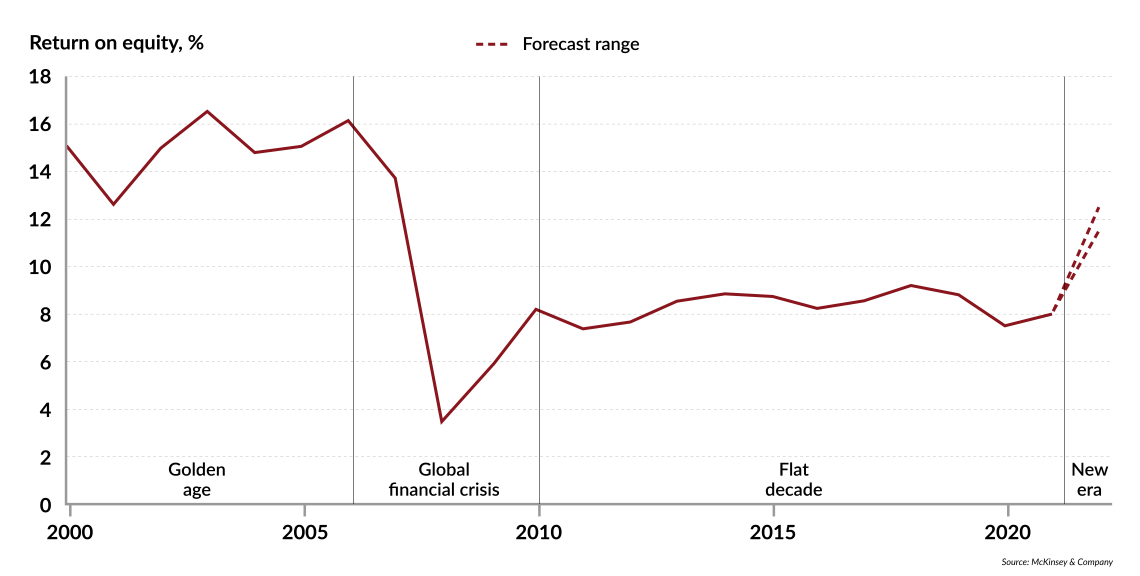

Fifteen years of stringent regulatory requirements and gloomy macroeconomic conditions have taken a toll on bank profitability, especially in Europe. But lately, a new wave of optimism is spreading over the global banking sector.

At first glance, bankers have at least one good reason to be cheerful again. Since July 2022, the European Central Bank lifted interest rates no less than 10 times. For its part, the American Federal Reserve Board proceeded to introduce 11 rate hikes over nearly the same period, offering banks a golden chance to boost earnings without any effort.

But what if banks’ newfound prosperity were due to something more than just a stroke of luck? After facing crisis upon crisis, have they finally found a way to turn threats into opportunities and weaknesses into strengths?

Indeed, there is a potential turning point. Artificial intelligence has what it takes to revolutionize the banking industry. But there is a catch: along the way, almost as a side effect, banks find themselves on the way to creating a surveillance system with unprecedented scope and intrusiveness.

Facts & figures

Banking profitability across the industry’s eras

Banks are splashing on AI applications

Since the end of 2022, there has been much hype around generative AI, which replicates humanlike content. For instance, ChatGPT, built on so-called large language-model technology, has become history’s fastest-growing online product. It took its creator (OpenAI, now partnered with Microsoft) only two months to reach a hundred million users worldwide.

Every day, new AI applications appear on the internet, turning all kinds of human activities upside down. While the AI frenzy is bound to recede in the long run, some sectors more than others might come out of it durably changed. Banking is one of them.

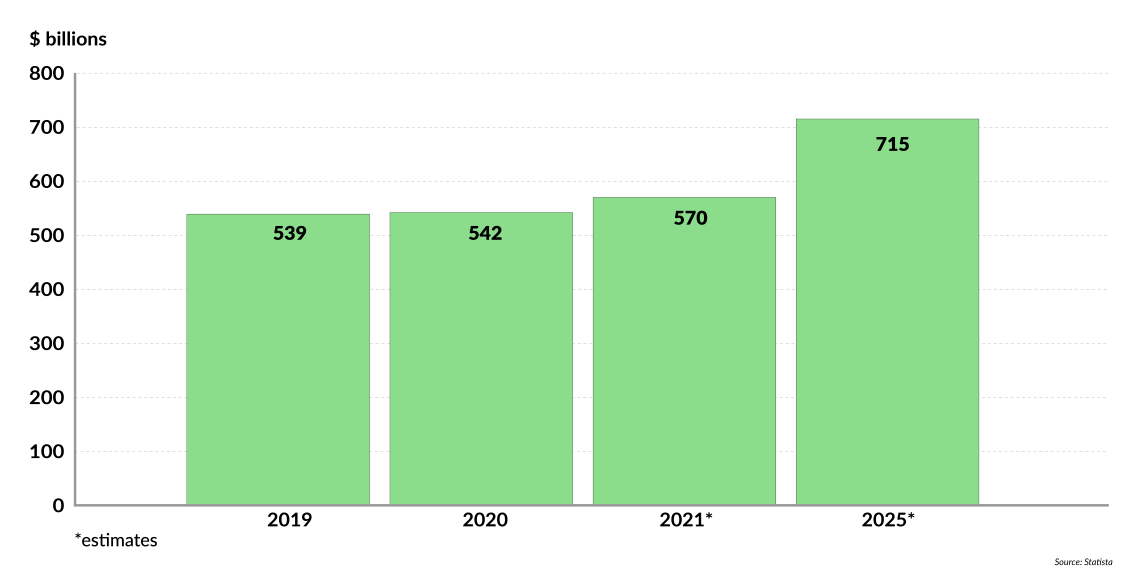

Facts & figures

Worldwide IT spending in the banking and securities sector, 2019-2025

Leading bank groups currently invest a lot of money in AI technologies. They compete fiercely to recruit top specialists who are a scarce resource in a market that needs them badly. Large American banks like JP Morgan Chase and comparably smaller European banks such as the Spanish BBVA have built their in-house AI research centers, led by eminent computer scientists lured away from prestigious universities, start-ups or big technological companies.

Early adopters hope to benefit from the competitive advantage they will acquire in an AI-dominated financial landscape.

A first benchmark (provided by data intelligence start-up Evident) already shows where the world’s leading banks stand in incorporating and advancing AI and machine learning. Unsurprisingly, JP Morgan Chase ranks number one, with an average yearly budget of $12 billion spent on technology that is to climb to a vertiginous $15.3 billion in 2023.

Early adopters hope to benefit from the competitive advantage they will acquire in an AI-dominated financial landscape. Those who miss the train could quickly be deserted by their customers and driven out of business, many bankers fear. So, even the skeptics in the banking elite think they have no choice but to meet the AI challenge.

New level of the game

AI/machine learning may be in its infancy, but it has already started changing how banks work.

On the security side, AI-powered firewalls help banks to better protect their IT systems against increasingly sophisticated and dangerous cyberattacks. So far, the use of AI for cybersecurity is still relatively limited, but this is about to change as innovation progresses fast. According to a CNBC report, the global market for AI-based cybersecurity products is estimated to reach $133.8 billion by 2030, up from $14.9 billion in 2021.

Virtual assistance and conversational interfaces could soon become the norm in interactions with banks. Today, banks’ inarticulate chatbots still frustrate many customers with their canned responses. But as algorithms are trained to provide more than just sterile copy-paste answers, banks hope for a cultural revolution in which clients learn to like dealing with bots.

Moreover, AI and machine learning will allow banks to personalize their services to a greater extent and, eventually, speed up credit decisions. Services can be tailored to the particular needs of each customer. More specifically, high-quality investment advice will be accessible to everyone. JP Morgan Chase recently filed a patent for a ChatGPT-inspired tool based on mining mountains of trading data to predict stock moves. It could guide consumers/investors in their investment decisions. The application, to be launched in 2026-2027 under the name IndexGPT, could put many financial advisors out of business. Also, thanks to AI, the quality of automated translation is improving daily, which allows banks (and a plethora of other companies) to enlarge their customer base.

The industry has increasingly turned to firms with so-called ‘regulatory technology’ (Regtech), allowing banks to computerize their reporting duties.

More generally, AI will boost banks’ productivity gains and, at the same time, reduce operational costs. Robotic process automation can already replace human employees for various operational tasks. AI-provided decision support systems will assist risk managers, wealth managers, HR managers and even top executives in their strategic choices.

Compliance breakthrough

Above all, AI and machine learning can alleviate one of the biggest burdens banks have had to face since the post-2008 regulatory boom. Compliance with innumerable, constantly changing international and national regulations, policies, laws, directives, guidelines, recommendations, technical standards and the like has become a nightmare for banks.

This time-consuming activity costs banks a lot of money but does not generate profit. In Europe, the costs related to data collection and reporting have been weighing heavily on banks’ bottom line. In recent years, the industry has increasingly turned to firms with so-called “regulatory technology” (Regtech), allowing banks to computerize their reporting duties. Undoubtedly, AI and machine learning will propel Regtech to the next level of compliance automation.

Already, banks rely on fraud detection algorithms trained on their customers’ historical data. On average, the data of a typical retail client can pop up tens of times a day on the control radar of banks using such AI models. The idea is to detect activities deviating from usual spending patterns, or anything that looks suspicious in some other way.

Reportedly, error rates of these monitoring procedures based on self-improving machine learning are considerably lower than those under human oversight. Were these algorithms to be generalized, a host of compliance officers could be sent home, and fewer employees would be needed to filter or verify, with increasingly powerful computers, information provided by customers.

Know Your Client (better than they know themselves)

It can be supposed that, for some time already, banks have been screening their clients’ financial data, not only to detect fraudulent behavior of the few but to study the life patterns of the many. How do the clients live, where do they work and how much do they earn? And what do they buy, what taxes do they pay and what health expenses do they incur? Banks want to know where their customers travel, what they do for leisure, how many children they have and with whom they live or socialize. Everything matters. Banks are increasingly aware that any information, not just financial data, can be valuable to them.

The most innovative banks are currently developing data collection methods that go far beyond capturing directly available information. Reportedly, their AI research departments are testing “web crawlers” that mine any public and private information to be found online about the banks’ customers. The tools systematically comb through social media pages, blogs and personal websites – wherever clients’ names pop up. Comments or opinions expressed by them on platforms such as Twitter, Facebook or Reddit are of particular interest. Tweets are classified according to a variety of criteria. Posts are analyzed through the prism of natural language processing, text analysis algorithms and computational linguistics.

Interactions clients have with bank staff are under scrutiny as well. Email exchanges, chats with bots, recorded phone calls or transcripts of onsite meetings are valuable sources of information. For AI, not only the content of conversations matters. The tone of voice, vocal bursts, laughter or twitches can be documented by “sentiment analysis” and considered when establishing clients’ trust- and creditworthiness.

Obviously, “emotion AI” is more than opinion mining, and sentiment analysis goes beyond polarities like “positive,” “negative” or “neutral.” AI models grasp with ever greater accuracy people’s emotional states (enjoyment, anger, surprise, disgust, sadness, fear, shame and deception…). An ever deeper “deep learning” is to be expected from these high-tech lie detectors that work with daily growing data sets. Scientists already test AI models that “guess” the missing data by connecting the dots.

That incentivizes banks to dig ever deeper into their account holders’ lives, even if their clients’ activities are fully legal. Banks need anything to put in their mandatory “Suspicious Activity” or “Suspicious Transaction” reports.

In constant symbiosis with everything around them, a vast arsenal of self-improving AI/machine learning tools capable of processing and sensing all kinds of information about the physical and the virtual world will allow banks to profile their clients with scary precision.

At present, only a handful of the biggest players are experimenting with insidious surveillance systems that hide behind a “consumer experience enhancement” smokescreen. But in the long run, this could well be the future of banking.

Incentivized to police their customers more

Such privacy-invading practices clash with banks’ duty of confidentiality. Bankers may justify them by arguing that spying on their customers is necessary to keep their institutions safe and, ultimately, to protect the crisis-stricken financial system. Moreover, “Know Your Client” (KYC) is a regulatory requirement, they will say.

They are right. Regulators force financial institutions to police their customers and signal to the supervising authorities any suspicion of money laundering, terrorist financing, tax evasion and other crimes or frauds. Supervising institutions watch banks closely to ensure they do their compliance job as required.

The supervisors reprimand financial institutions that have not detected “enough” suspicious cases. That incentivizes banks to dig ever deeper into their account holders’ lives, even if their clients’ activities are fully legal. Simply put, banks need anything to put in their mandatory “Suspicious Activity” or “Suspicious Transaction” reports.

From a burden to treasure trove

Over the past decade, nonbank financial institutions such as fintechs or BigTechs have started to offer financial services outside the traditional banking system. Needing no banking license to do so, they could comfortably make money on bank-like activities and yet avoid the regulatory conundrum ordinary banks are struggling with.

Surprisingly, BigTech companies now seem eager to give up that considerable advantage. Some try to acquire banks. Others directly file for a banking license.

Scenarios

Why would BigTech firms want to become banks if this status has a downside? The answer is simple.

Banks enter the data economy

For years, Facebook, Google and others have been accused of massive “data theft.” In Europe, laws have been designed to break the so-called “surveillance capitalism” business model based on extracting personal data from one’s customer base and selling it to advertisers.

A bank license would allow BigTech companies to transform their increasingly denounced core activity into regulatory obligation. If these companies were registered as banks, they could conveniently go on violating clients’ privacy simply by invoking Know Your Consumer requirements.

In other words, the genie is out of the bottle. While Big Tech is drawn to banking, banks are drawn into the data economy.

After complaining for years about unreasonable reporting requirements, banks have realized that the vast amounts of data they were forced to collect on behalf of supervisors can be pure gold. So is the know-how and expertise they acquired in doing so.

The burning question is this: If Facebook and the like can sell their users’ personal data, why should banks not do the same?

A formidable business opportunity

Thanks to AI and machine learning, banks are about to rethink and reshape their business models profoundly.

Selling data could bring back the industry’s long-lost profitability. But this would be a tremendous shift. Historically, the banking business has been about confidence or trust. However, since regulators have started misusing financial institutions to police their customers, the mutual trust between banks and clients has been profoundly strained. Soon, as the regulatory burden can be transformed into a formidable business opportunity for banks, the financial sector has the potential to turn into a lucrative global surveillance system.