Asset price inflation and broken market forces

Over the past several years, much has been said and written about the state of the financial markets and the ongoing bull run, particularly in United States equities, which seems even more striking when compared to data from the real economy. The decoupling between stock markets and the broader economy, which has been underway for some time, is becoming more evident. This phenomenon not only exacerbates sociopolitical divides and concerns about inequality, but it also poses extreme challenges for ordinary people planning their finances for themselves and the next generation.

The absurdities of modern valuations

In August, the American chip manufacturer Nvidia Corporation reached a market capitalization of approximately $4.4 trillion. This figure alone is astonishing, but it becomes even more impressive when put into perspective: It surpasses the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of Japan in 2024, which was $4 trillion, India’s GDP of $3.91 trillion and the entire market capitalization of the Swiss Stock Exchange, at about $2.7 trillion. It also dwarfs the total value of all agricultural land in the U.S., estimated at about $3.3 trillion. Even compared with the estimated value of all the gold ever mined, roughly $22.8 trillion at a price of around $3,335 per ounce, Nvidia’s valuation represents a significant fraction.

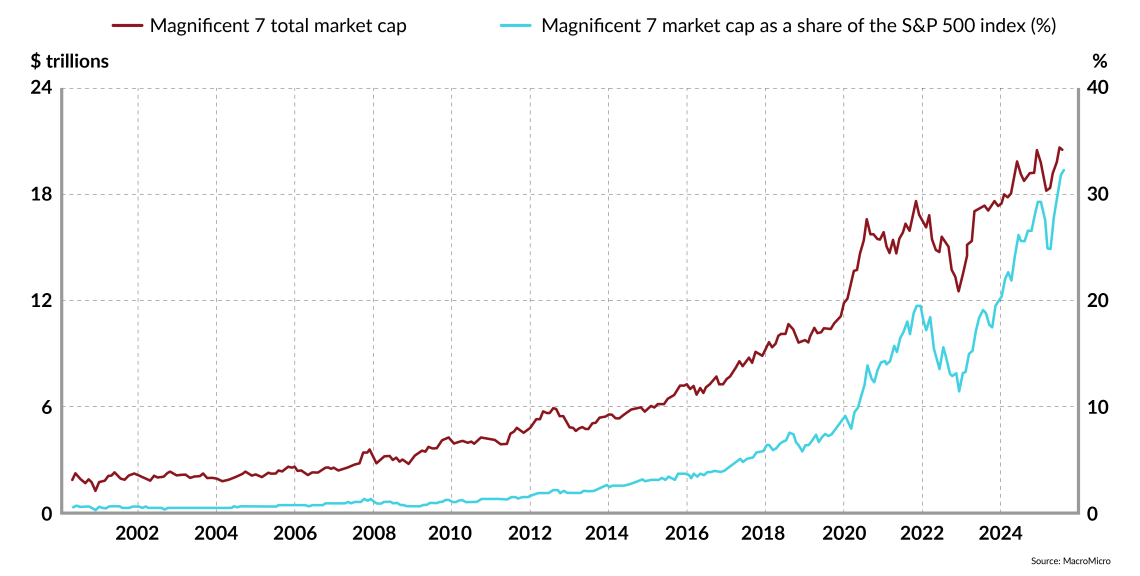

Nvidia is an extreme example, but not an isolated case. The so-called “Magnificent 7,” which includes Nvidia along with other American tech giants Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta and Tesla, collectively have a market capitalization of over $19 trillion as of mid-2025. This amount exceeds the GDPs of several major economies combined. It clearly highlights a broader trend of asset price inflation and the decoupling of stock valuations from fundamental economic realities. These worrying distortions cannot simply be dismissed as run-of-the-mill market exuberance, but instead reveal deeper, structural vulnerabilities within the current financial and monetary system.

Facts & figures: The Magnificent 7’s market cap vs. the S&P 500

The roots of the problem

Asset price inflation is by no means a new phenomenon. It dates back decades, arguably beginning with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s. However, it has become more pronounced since the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession and the (at the time) extreme measures that central banks took to navigate it.

Quantitative easing (in which central banks purchase government bonds to inject money into the economy), low and negative interest rates, and excessive borrowing and spending by governments have contributed to the flooding of the system with artificial liquidity. This has also encouraged excessive debt issuance and malinvestment (poor or misguided investment) by corporations. The Covid-19 crisis supercharged this cause-and-effect relationship. The scale of quantitative easing and government spending during and after the pandemic has surpassed anything else we have seen before. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in the massive inflation wave that affected both consumer and asset prices.

Facts & figures: What is asset price inflation?

Asset price inflation refers to the rise in nominal prices of assets such as stocks, bonds, gold and real estate. When the term “inflation” is discussed, it typically refers to consumer price inflation, not the rising value of financial or capital assets. Unlike consumer price inflation, which tracks the cost of everyday goods and services through metrics like the Consumer Price Index, asset price inflation is not included in these indicators.

While surging asset prices may suggest economic growth, they do not reflect actual production, as measured by GDP. Instead, financial assets can be volatile, often creating an illusion of prosperity through bubbles. An asset price crash often follows asset price inflation.

A key mechanism to understand here is the Cantillon Effect, named after the 18th-century economist Richard Cantillon. It explains how changes in the money supply, particularly through the printing of currency, redistribute wealth and distort relative prices. Specifically, it highlights that newly created money enters the economy unevenly, benefiting those closest to the source of the money, typically banks and large corporations.

As central banks inject “fresh” money into the system through private banks, it drives up asset prices, from equities to real estate. By the time this money reaches the broader population, prices have risen so much that ordinary citizens not only fail to benefit but often struggle to meet housing costs. This further widens the inequality gap and perpetuates the socioeconomic divide.

Artificially low interest rates are also a major contributor. When borrowing becomes unnaturally cheap (or, in Europe’s case, even profitable through negative interest rates), all rational incentives and fundamental laws of economics are disregarded. This phenomenon was evident in recent years when many companies’ stock prices reached unreasonably high levels through stock buybacks.

This means that companies bought back their own shares, which reduced the number of shares available and inflated stock prices. This does not reflect real growth; it merely makes the company appear more valuable on paper. Instead of investing in new technologies, equipment, talent or anything else that would benefit the business in a real, tangible way, many companies simply borrowed at low rates to buy back their own shares.

At this point, it should be clarified that rising stock prices are not always a negative and that in some cases, revenue growth also plays a crucial role – although, in most cases, it does not account for the full picture. Apple is a prime example: Its 2024 revenue reached $391 billion, which exceeded the GDPs of around 75 percent of the world’s economies, including Finland (almost $300 billion) and Qatar ($218 billion). Its AirPods product line alone generates revenue estimated at over $18 billion annually, which is comparable to Malta’s 2024 GDP of approximately $24 billion.

Social and economic ramifications

All this has led us to our current predicament, where asset prices no longer reflect intrinsic value, productivity or investor confidence in future performance. Instead, they are more accurately described as knee-jerk reactions to monetary and fiscal stimuli. This is how we ended up with a financial landscape riddled with bubbles, with companies like Nvidia trading at multiples that defy historical norms, often surpassing their earnings 50 times despite cyclical risks in the semiconductor industry. For everyday investors, this means that the traditional price discovery mechanism of the market is all but irredeemably broken due to numerous distortions, leaving them with mounting challenges when planning their financial future.

The same applies to professional investors, as demonstrated by the latest Bank of America monthly survey of fund managers who manage nearly half a trillion in assets. A record 91 percent of the portfolio managers surveyed said U.S. equities are overvalued. Yet, they remain fully invested, with cash as a share of assets staying near historical lows at 3.9 percent. This implies that while they recognize the assets they hold are overpriced, they either do not see it as a problem, or more likely, they simply lack other realistic options to deliver performance results.

Asset price inflation also has a significant impact at a socioeconomic level. The growing inequality gap has the potential to trigger serious political destabilization and erode social cohesion. As the “have-nots” continue to drift further from the “haves,” the once-promising prospects of upward financial and social mobility are increasingly seen as mere illusions.

Scenarios

Most likely: Economic disparities grow, and asset prices soar

Going forward, the most likely scenario is that governments and central banks will continue their policy of “printing and spending,” which will inevitably exacerbate economic disparities in most nations and drive even more extreme valuations. Periodic corrections in asset prices will occur as they have in the past, but they will be masked by further liquidity injections, which will, as has been the case so far, penalize ordinary people through consumer price inflation and benefit large financial institutions and corporations.

Unlikely: Asset price bubble is gradually corrected

Another possible outcome would be to find a way to deflate the current asset price bubble without causing catastrophic domino effects. This could potentially be feasible through fiscal discipline and gradual monetary tightening. But this is largely unrealistic, as it would cause substantial financial pain in the system, rendering it politically untenable.

Somewhat likely: Current debt bubble bursts, leading to a collapse in asset prices

Finally, it would not be too far-fetched to imagine the worst-case scenario: The largest debt bubble in history, which we are currently experiencing, could burst, causing a cascade of asset price crashes. This system-wide deflationary disintegration would lead to widespread defaults and recessions worldwide, resulting in extreme crises and economic hardship across the board. However, it would also purge excesses, eliminate distortions and create the conditions for a genuine recovery.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/asset-price-inflation/