The new geopolitics of trade in Asia

The era of Western-led globalization has been replaced by a developing struggle between the United States and China. From a Western point of view, the major challenge emerges from a competition between nations that support liberal values and proponents of authoritarianism, with profound implications for the global economy.

Mixing international trade with geopolitical rivalries is going to be the new norm. This is a regrettable development, even more so because most Asian economies – and particularly the success stories of China, South Korea and Japan – were able to grow thanks to access to global markets and expanding trade.

The Chinese economic miracle would have been impossible without these opportunities. Had the West not built the post-World War II structure of international trade and finance, China could have never emerged from the poverty it suffered after the death of former Chinese leader Mao Zedong. In a sense, one might think that China should today be paying back this debt, taking on responsibility for supporting a functioning world economy. Instead, trade in Asia is regressing. (This is not to overlook the role of American policy, during both the Trump and Biden administrations, in politicizing trade in Asia.)

The major uncertainty lies in the Global South. While not as prominent as the Non-Aligned Movement of the Cold War, the Global South is now one of the major geopolitical challenges facing the West, particularly on issues around trade.

Three rival structures

The Far East today lacks a comprehensive security architecture. There are bilateral treaties like those between the U.S. and Japan and the U.S. and South Korea. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) serves as an established multilateral organization, providing a framework along the lines of other continental bodies such as Mercosur, the South American trade bloc.

In economic and trade issues, there are three organizations – Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) – which must be seen as geopolitical rivals.

Facts & figures

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

- Established in 1989

- 21 members: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, the U.S. and Vietnam

- Based on three pillars: trade and investment liberalization, facilitating a positive business environment, and economic and technical cooperation

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)

- Established in 2012

- 15 members: Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam

- Reached a free trade agreement in 2020

Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF)

- Established in 2022

- 14 members: Australia, Brunei, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, the U.S. and Vietnam

- Based on four pillars: trade, supply chains, a clean economy and a fair economy

All three organizations have made lofty declarations in favor of economic cooperation, trade and development. Their true intentions are revealed in their membership. APEC is the most established of the three and the most diverse, counting rivals like the U.S., China and Russia. Notably, for the forthcoming annual meeting, set to be held in the U.S., Washington has banned Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee but confirmed that there is no bar on Russia’s participation.

The RCEP is a Chinese initiative, and its membership suggests that Beijing aims to create a following of economically relevant states to support its own international trade agenda. India and the U.S. are outside of the group. Instead, it includes countries that are strongly dependent on China and whose regimes are on the outs with Washington, such as Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia.

The IPEF is the most recently launched forum, aimed at furthering American geopolitical interests in the Indo-Pacific region. This is evident in its composition, which includes Australia, Japan and India – countries playing a key role in the U.S. strategy to contain a rising China.

Australia, despite some trade disputes with China, belongs to all three organizations. Similarly, Japan – which long kept a low profile in multilateral initiatives beyond its security treaty with the U.S. and its presence in the G7 – is also a member of each grouping.

Trade issues have always been part of politics, and organizations like the World Trade Organization and the European Union were designed in part to tear down restrictions on free trade. But the present times are especially fraught with risks around trade. During the Cold War, the West had to deal with powerful military threats posed by the Soviet Union and its allies. However, the USSR was of little relevance to the world economy. The West could establish a world economic order that was largely built on a market economy and free trade values. Even beyond the Western alliance, like members of the “nonaligned” countries, there was no other option but to deal with the West on its own terms.

This fundamentally changed with China’s emergence as one of the world’s largest economies. The roots of this new challenge lie in the historic reforms launched by former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. Pragmatically, China maintained its one-party system while at the same time opening up major elements of its economy – if not to a full-fledged market economy, then one that allowed Western investors, technology and businesses to enter.

Beijing opened the economy to its own version of private enterprise, meaning that non-state actors were allowed to operate wherever they did not infringe on the general, party-dominated economic framework. With the Western world keen on economic interaction, China sought to make its economy more competitive in world markets.

In the global economic picture that has developed over the past three decades, China competes in Western markets through existing frameworks – for example, in capital markets and by acquiring Western companies to gain access to technology and intellectual property – while maintaining its own unique economic model. Despite talk of free markets, the Chinese economy remains one fully controlled by the Party.

Facts & figures

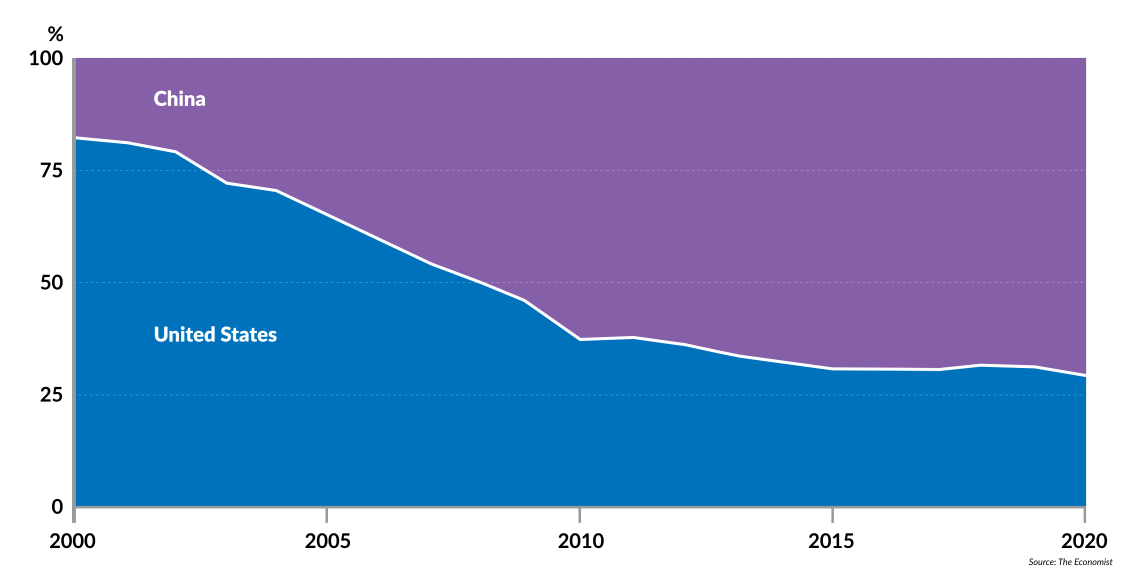

Countries sharing greater trade with the United States or China

For some time, the West overlooked the challenge presented by this dynamic, presuming that it could deal with China like an ordinary market economy. Now that Western governments have woken up – particularly the U.S., with Europe following haphazardly – they face another challenge. Washington has decided that this is the moment to address the risks posed by Beijing, with politicians from both sides of the aisle declaring China as the country’s main adversary. Besides the highly dangerous possibility of an open war, there are rising prospects of long-term economic conflict.

The historic rivalry between the U.S. and China is, for now, being fought on economic terrain. Washington has moved from the so-called “pivot to Asia” under the Obama administration to a policy of containing China’s rise. The main goals are the reindustrialization of America and preventing advanced technologies from reaching Chinese companies, particularly in the field of information technology.

This is unfortunate for countries (such as Switzerland) that depend on open markets and on trade policies based on economic, rather than geopolitical, criteria. There is considerable collateral damage when ostensibly free-market nations like the U.S. turn to economic populism, alongside more mercantilist states like China and India.

Scenarios

U.S.-China detente

The most beneficial scenario for the global economy would be a settlement of the superpower struggle – a recognition that the new world order is based on a U.S.-China duopoly, and that both powers share a duty to provide stability. When former American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger recently met with President Xi Jinping in Beijing, there were no doubt reminiscences of the era when China began rising. Then, the U.S. was able to see mutual benefits, supporting China’s industrialization to the boon of American corporations and consumers.

At some point, it may dawn on policymakers in both Washington and Beijing that trade restrictions and regulations are helping nobody. Such a development could help reduce the influence of geopolitics in global trade, and the three multilateral Asian structures could help promote a Deng-style revival of pragmatism in China.

Opportunity for Japan

A second scenario would see those countries belonging to all three geopolitical forums promote a constructive approach involving all parties. The most important of these is Japan. Tokyo has long been reluctant to develop a high profile in geopolitics. This is changing, with the Japanese aware that, amid threats coming from China and Russia, they are the most vulnerable player in the Far East.

Heightened conflict

A third scenario would be a hardening of trade conflicts – not only in terms of import restrictions but also of export bans aimed at constraining supply chains and exploiting economic vulnerabilities. In this situation, the RCEP and IPEF would grow in importance, becoming new fronts in the superpower rivalry. Some countries that now belong to both would have to make a choice. This would have repercussions beyond the Indo-Pacific region, particularly for the European Union.

The original report was published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/geopolitics-trade-asia/