America’s misguided monetary interventionism

This article addresses America’s current financial and economic situation. What it is not, is a treatise on tariffs or US politics – those two topics have been very thoroughly covered by a plethora of commentators. Rather, our focus herein is to examine America’s situ by employing the Austrian business cycle’s theoretical framework to better understand the issues facing US consumers, investors, politicians, and businessmen, and suggest a likely more productive path forward than the monetary interventionalist approach that has been in vogue ever since the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 (the “GFC”).

US financial markets are currently engulfed in a period of heightened volatility. However, the extent to which this volatility is the result of increased geopolitical uncertainty remains to be seen. That the turbulence coincided with the inauguration of President Donald Trump and the implementation of trade tariffs should not automatically imply causality – a case of post hoc ergo propter hoc. As George Friedman observed in The Storm Before the Calm: “Some presidents like Lincoln, Nixon, and Trump are reviled by some and loved by others, but the reality is that they are not powerful enough to be causing the problems – nor in control of the underlying currents they are riding.”[1]

Friedman’s point is a good one, especially with regard to phenomena that take years – even decades – to grow, develop, and eventually unfold. Yes, Presidents do hold considerable sway over economic matters – significantly more than America’s Founding Fathers intended, but that is a different topic. What is key is that modern financial markets and economies are larger than any single individual.

To be sure, the actions of key individuals – presidents, central bankers, certain CEOs, the occasional academic – can have both short-term marginal effects and adjust society’s longer-term trajectory. President Franklin Delanor Roosevelt had a lasting impact on America, just as Margaret Thatcher did on Britain; the writings of Sigmund Freud had a profound influence on how people view the world, as did Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity.

Financial crises don’t simply pop out of thin air; the same is true for economic and business cycles. The GFC had its roots in government policies to make housing more accessible – policies that can be traced back to the end of WWII when American politicians wanted to make home ownership more accessible to returning veterans – coupled with deregulation and the packaging and selling (aka, securitization) of loans. Of course, there were other factors. The point is that the GFC didn’t appear ex nihilo. The same is true for the current turbulence we’re seeing.

In 2008, by the time then US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke appeared in front of Congress (hyperbolically) asking for authorization of an unprecedented $700 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (“TARP”) to essentially bailout a number of financial institutions that were teetering on the edge of insolvency, the dye was pretty well cast for how the crisis would play out with regard to governmental policy.[2] But something else about the Hank-Ben appearance in the Fall of 2008 was notable in addition to its tone of panic: it set a modern precedent for explicit government intervention into the financial services industry, not to backstop investors, but save the institutions themselves. The “Hank-Ben Bailout” was aimed at financial intermediaries – at the institutions – not intermediation, or the individuals who provide, via savings and the purchase of stocks and bonds, the raw materials with which banks extend loans.

As we know now, the immediate impact of the Hank-Ben Bailout was largely successful in terms of providing capital to bank holding companies[3] and at least partially calming panicking investors. However, there were two broader impacts as well. The first established the precedent that the Federal Reserve (with the help of Treasury) would step in, should the situation arise.

For years leading up to the GFC, those of us who worked in Finance had discussed the “Greenspan Put.” Simply stated, the Greenspan Put was the idea that if things ever got really bad in financial markets, the Federal Reserve (of which Alan Greenspan was then Chairman) would come to the rescue of the financial organizations it oversaw, including all the large investment banks and broker-dealers. The very presence of the Greenspan Put created a moral hazard that promoted excessive risk taking, which is, of course, exactly what investment houses did.

The second legacy of the Hank-Ben Bailout was that – in the minds of many politicians, academics (regrettably), bankers, and businessmen – it perpetuated the idea that Keynesian intervention could not only postpone a crisis but also actually solve the underlying problem(s) that had created it/them. In short, the actions taken to stave off what would have been considerable damage of the GFC validated the Keynesian narrative.

Moral hazard is like a ticking time bomb. When times are good, there isn’t a problem. It is only when things go bad that the full extent of the hazard is realized, and the bomb explodes. Similarly, the perceived comfort that lies at the heart of Keynesian intervention is incredibly seductive to bankers and businesses: Whatever happens, the government is there to bail us out, if we can just make sure that the damage caused by our behavior is large enough that it poses a threat to politicians’ constituents.

Austrian macroeconomic capital theory is founded largely on the work of Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and was subsequently more fully articulated and bolstered by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek. At the heart of the business cycle theory lies the notion that monetary forces cannot materially alter the natural cyclicality of business. Or, in economic jargon, Austrian business cycle theory maintains that, while the consumption-investment tradeoff present in classical economics is valid, an economy can function both beyond and below the production possibilities frontier (“PPF”) due to exogenous intervention in the form of monetary policy (aka, the extension of credit), but any activity beyond the PPF will eventually lead to a negative response that will overshoot the equilibrium PPF and ultimately cause hardship.

Stephan Erik Oppers,[4] in his survey of the principles of the Austrian business cycle provides the following summary of what transpires when an artificially high amount of credit is introduced into an economy:

The initial credit-induced changes in investment were not based in [sic] preferences and thus prompted a mismatch between the structure of production and planned future consumption. This triggers a recession. Attempts by the monetary authorities to stave off recession are doomed to failure; the economy needs time and unfettered interest-rate signals to readjust its capital base to the structure of demand.

Time is the key – as it was for Bohm and his colleagues. Yes, intervention (aka, lowering interest rates) can “kick the can down the road” a bit by providing artificial stimulation, but eventually the economy must “reset” to a level that is based on fundamentals.

There are multiple dynamics concurrently taking place that affect US markets and its economy. Many of these are items such as tariffs, which lie outside of this article’s scope. The same can be said of other political decisions. And there are a multitude of moving economic pieces as well. However, our focus herein is the legacy of the GFC, and the likely forthcoming economic reckoning that the US will be forced to endure. After all, you can only kick a can down the road for so long. Eventually, you run out of road.

Very roughly, there are three major stages in the Austrian business cycle,[5] the first of which is a “boom period,” characterized by heightened investment (by businesses) and consumption (by individuals). This period is brought about by inappropriately low interest rates (aka, those below the “natural rate”) [that] provide excess credit that outstrips rational, appropriate investment opportunities.

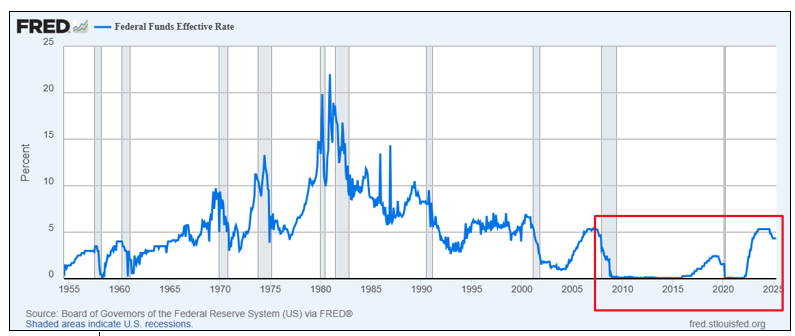

Beginning at the end of the GCF, the Federal Funds Effective Rate was in a range between 0.00% and 0.25% for nearly five years.[6] In January, 2016, the rate climbed to 0.29%, beginning an upward trend that lasted until the spring of 2019 when it reached 2.25%. Then, the COVID Pandemic struck, and humanity went berserk.

To combat the ensuing weakness in financial markets[7] and the real economy that resulted from a staggering number of people going into hibernation, the Federal Reserve lowered rates to virtually zero (again), only allowing them to begin to rise again in early 2022.

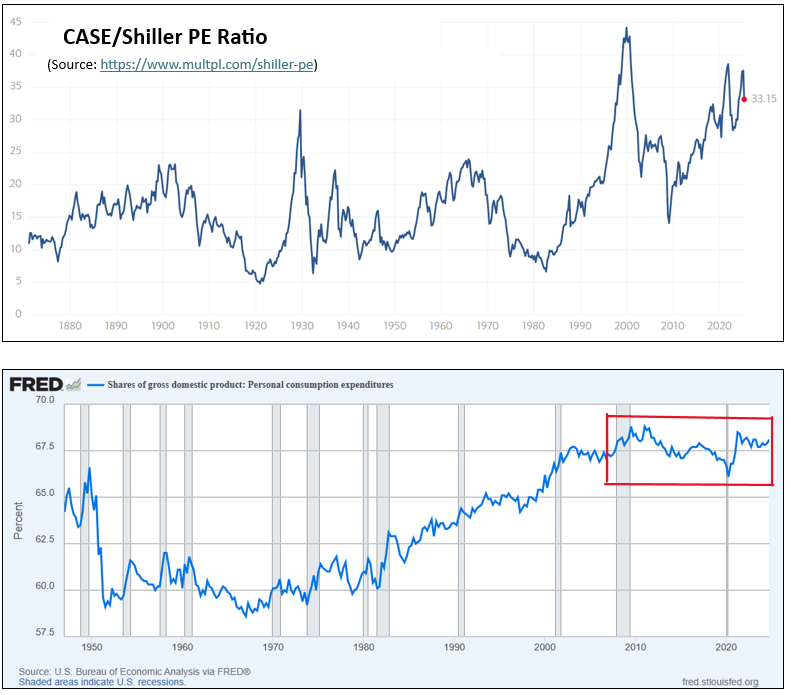

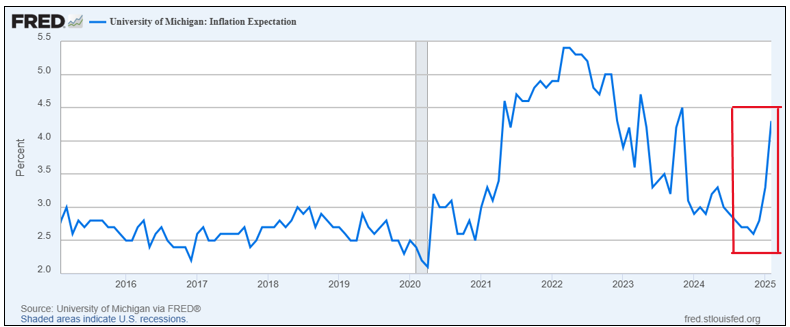

While politically expedient and widely popular (in general), the natural result of such low rates was to turbocharge credit availability and utilization. And that is exactly what happened: businesses and consumers went on an investment and spending spree, respectively. The trouble was that there were not enough economically rational – a phrase that, herein, refers to any investment that has a suitable risk-reward profile – investments to keep up with demand. The result was twofold, just as Hayek and others had predicted: (1) financial asset prices rose beyond levels that were, by virtually any metric, reasonable; and, (2) consumption spending and investment in production capabilities ballooned.

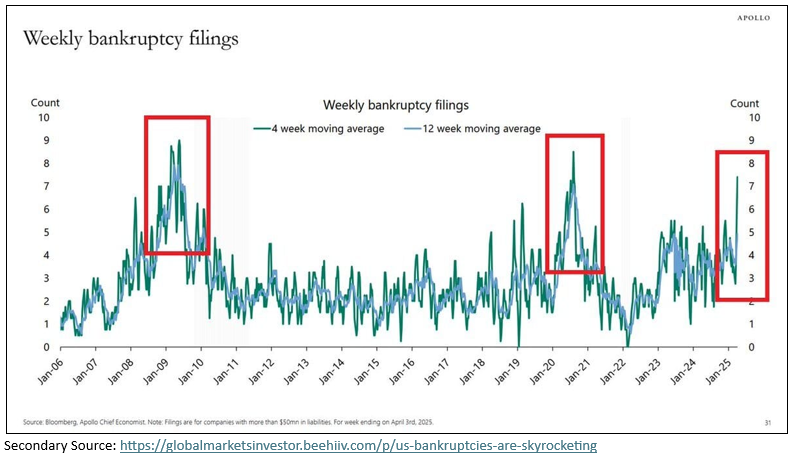

The US economy is now standing at the gates of the second phase of the Austrian business cycle, which involves a credit crunch[8] (and concurrent decline in spending) and the liquidation of various investments to pay creditors. These are the bad days. For many Americans, the pain has already begun; for others, it isn’t far off; for too many, it is inevitable.

In addition to the human toll that credit crunches take, the economic damage is palpable. As the above chart shows, nearly 70% of America’s GDP is from consumer spending. “As goes the consumer, so goes the economy.”

That said, we need to address an apparent contradiction with the Austrian theory, which is the overinvestment during the first phase that also sees delayed consumption due to the trade-off between savings and spending. Clearly, such a dynamic has not taken place in the US. But, it has on the global state, especially in China. Essentially what has happened is that the US provided capital and credit for Chinese investment – funding that the Chinese government (along with that of other countries, such as Viet Nam, Taiwan, and others) has used to significantly build out not only their factories, but also their infrastructure. Of course, foreign consumers have done their share of consuming as well. However, make no mistake, Asia has focused very heavily on investment.

Whether China’s production capacity buildout has reached the point of “malinvestment” remains to be seen, but so far, the evidence certainly does not contradict such a claim. In short, it turns out that Hayek’s infamous “forced savings” has been taking place – just not in America. And while China et al have been investing, Americans have been consuming. In fact, US consumption has been so great that it has far outstripped any semblance of sustainability.

Indeed, it seems that every few days a new chart appears, or a report is published, confirming that US consumers are over-levered and in poor financial shape. And the specter of declining consumption – either because of budget constraints or the negative wealth effect – is noticeably present, and a topic readily discussed among bankers and portfolio managers.

Americans have had a grand time taking advantage of the unsecured purchasing power afforded to them by easily attainable credit cards – a staggering number of which have rates north of 20% – and buying everything from cars to boats to ATVs (whatever those are) by utilizing in-store financing.

Naturally, real estate prices have risen: the median price for a new home (aka, one that was already standing) climbed by 42% since the end of the Pandemic, according to the National Association of Realtors. Likewise, most categories of real estate increased dramatically: housing starts are up (albeit still below the boom-time levels seen from 1995 to 2005), as are the number of households that own a second (usually vacation) property.

The key point is that Americans have been spending money, even if they have to borrow to do it, on consumption. And therein lies the problem – a subject I addressed in my article, “Color Me Dubious,” for ECAEF on 27 October 2024, and have also mentioned previously herein. But whereas China’s credit-fueled malinvestment at least has the virtue of tangible production capacity – even if it is overbuilt – all Americans have to show for our purchases are toys that require maintenance, depreciate rapidly, and epitomize planned-obsolescence.

Where are we in the second phase? As always, it is difficult to tell. Capital markets seem to have reached a point where they will not continue much higher. Whether we have “put in a top” remains to be seen. But it does seem clear that the rate of growth markets exhibited over the past few years – the second derivative of the stock market’s arc, so to speak – is either dramatically slowing or has actually come to an end.

America’s employment situation is no rosier than its consumers’ balance sheets. The US is beginning to see cracks develop, whether in the guise of the number of individuals working multiple jobs, or those who have “dropped out” of the workforce (i.e., are no longer actively looking for work), or layoffs. The official US unemployment rate remains fairly low, for now [see first chart below] – although this is a trend that Americans do not expect to continue [see second chart below].

With all the negative sentiment among consumers, it should come as no surprise that many pundits are calling for the same “remedy” that was tapped during the GFC: loose monetary policy to expand credit with the goal being to stimulate the economy by keeping consumers spending. However, unlike the GFC, the trouble isn’t a lack of liquidity, but the opposite: Americans have too much money (and credit). The only thing that accommodative monetary policy would likely accomplish at this point is to increase inflation.

Austrian business cycle theory is clear with regard to the futility of efforts to “spend your way out of a downturn” – aka, the great “Keynesian lie.” Governments (including monetary authorities) cannot legislate or force the demand curve to move. The idea of “pushing the demand curve” is frankly ludicrous – seductive, yes, but without merit. However, this is exactly what many modern governments are attempting.

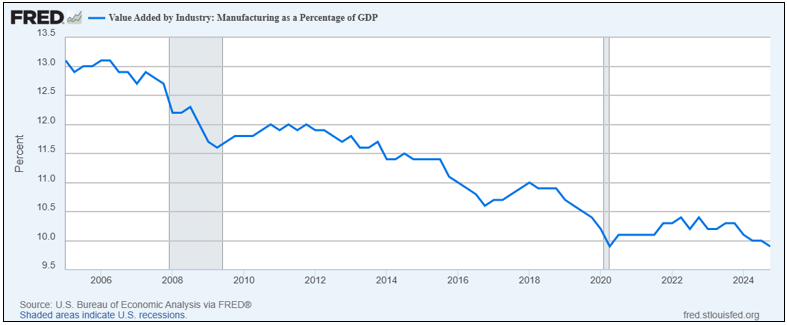

The simple fact is that, sooner or later, economies must enter the third and final phase of the Austrian business cycle, which is the adjustment period when resources are reallocated (based on preferences, not interest-rate manipulation), and the economy enters a period of healing and healthy growth, which is precisely what must take place now in the US. Americans must reduce their reliance on credit – of that there is no doubt. However, the US economy must also undergo a more fundamental transformation, one that reverses the trend of shrinking value-add component of America’s domestic manufacturing base.

Change is difficult and growth involves pain. Anyone who has ever trained for a sports competition knows this, as do those who have tried to understand multivariate topology. The troubling truth is that – based on the Austrian model – equilibrium lies only at the distant end of this journey. First, the economy must “overshoot” its natural equilibrium, dropping below the PPF – essentially like overcorrecting when driving on a slippery road. Then, and only then, can equilibrium eventually be achieved. One of the major difficulties for such realignment is globalization. Another is politics. Arguably the most tangible obstacle is the simple fact that people are generally averse to pain. There is a reason the Aiguille du Midi cable car is popular: everyone wants to ski down the Vallée Blanche, not hike up it.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, the past few weeks have seen extraordinary movements in the stock and bond markets. Volatility has gone practically vertical, and the S&P 500 appears to be responding solely to messages on social media, as do Treasuries, particularly on the long-end of the curve.

Financial market volatility is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, for traders, volatility is a blessing because it creates opportunities for profit. As Ed Wachenheim, CEO and chairman of Greenhaven Associates, notes:

Investors should treat volatility as a friend. High volatility permits an investor to purchase stocks that are particularly depressed and to sell stocks when they are selling at particularly high prices. The greater the volatility, the greater the opportunity to purchase stocks at very low prices and then sell stocks at very high prices.

But widespread, extreme volatility that stems from current economic (including policy) uncertainty is something different. The difficult part, naturally, is distinguishing between the root causes and determining whether financial volatility is an indication of economic uncertainty.

The unintended consequence of dramatically increased moral hazard that the Hank-Ben Bailout created is the most likely candidate for such high levels of volatility in financial markets. Yes, uncertainty over trade policy is a contributing factor as well. However, when the market forces that should have punished excessive risk-taking on the part of financial institutions during the GFC were not allowed to fully play out due to the government’s interventionist policies, a key aspect of capitalist natural-selection – the “destruction” portion referred to by Joseph Schumpeter – was removed. And with that loss, the uncertainty regarding future actions – of both the timing and extent the government can (or even will) intervene into financial markets and the economy – dramatically increased, the effects of which are still being felt by current investors.

In this article, we have proposed that the global economy is shifting in accordance with the Austrian business cycle because of the prolonged, destructive overuse of credit, which has resulted in a misalignment between consumer preferences, production capabilities, and budget constrains (aka, what people want, what is available, and what they can afford). That cycle is one that has happened before and will surely happen again.

One of the most prevalent legacies of the Hank-Ben Bailout is the fallacious notion that the government can “manage” the economy efficiently – a fallacy that has led to increased moral hazard and which, ultimately, is contributing to greater current volatility in US financial markets. If America is to retain its economic standing and financial leadership role into the middle of the 21st century, the tendency to yield to interventional policies must be tempered, if not reversed. Instead, politicians and their constituents must recognize the inescapable nature of economic cyclicality and learn to live in harmony with business cycles instead of tilting at windmills. As Don Quixote so aptly told Sancho, “Fortune is guiding our affairs better than we ourselves could have wished.”

[1] Friedman, G. (2021). The Storm Before the Calm: America’s Discord, the Crisis of the 2020s, and The Triumph Beyond. Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House.

[2] Ultimately, the entire $700b amount was not utilized. Rather, somewhere between $450b-$500b was lent out, much of which yielded substantial dividends and was paid back. In other words, it wasn’t a bad investment. The Quantitative Easing (QE) programme, on the other hand, proved considerably more difficult. In September, 2008, all the Federal Reserve Banks held combined assets of $926mm. One year later, that total had more than doubled to $2,140mm, some of which remain on the books even today. The QE programme was, basically, was a scheme by which the FRBs acted in its capacity as the “lender of last resort” and provided liquidity for banks with illiquid assets. While initial statements maintained that the illiquid paper would only be held on the FRBs’ balance sheets for a temporary period, that has not proved to be the case.

[3] Funds also found their way to Crysler, General Motors, and AIG. While it is reasonably easy to rationalize supporting to AIG because of its intricate linkage to major financial institutions via CDS and similar instruments, the case for funding Crysler (which was owned by a hedge fund, Cerberus Capital Management, at the time) and GM is significantly more economically questionable.

[4] Oppers, S.E. (2002). The Austrian theory of the business cycles: Old lessons for modern economic policy?. IMF Working Paper, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp0202.pdf.

[5] Depending on the source, the Austrian business cycle has more than three phases. For instance, the Misses Institute identifies five in its online review of the topic: (1) monetary expansion, (2) unsustainable boom, (3) upper turning point, (4) liquidation phase, and (5) recovery. I have aggregated those five into three, by combining the first and second and the third and fourth. While purists may (justifiably) find fault with this – or simply think it is lazy – the aggregation serves our purposes here.

Additionally, in a practical sense, the line-of-demarcation between monetary expansion and an unsustainable boom is grey at best, as is separating the upward turning point and the liquidation phrases, especially because, in both cases, there is overlap. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, a more definitive demarcation is possible. However, this article is about where we are now and where we’re going, even if we begin by looking at where we’ve been. As such, we lack the benefits hindsight affords.

[6] Prior to the GFC the Federal Reserve had set a single target rate. The adoption of a range was one of the changes enacted under the Bernanke Fed.

[7] Three of the largest twenty single-day declines in the S&P 500 occurred during March, 2020.

[8] “The SCE Credit Access Survey [conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Center for Microeconomic Data] points to an expected future tightening in credit conditions, consistent with the February core Survey of Consumer Expectations where the share of respondents reporting that they expect it to be harder to obtain credit a year from now jumped to 46.7 percent, the highest since June 2024.” Additionally, the Survey found that, “The average likelihood of being able to come up with $2,000, if an unexpected need arose within the next month, declined to 62.7 percent, a new series low.”

(https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/sce/credit-access#/)