A transatlantic reset

At the Munich Security Conference, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz delivered a remarkable speech. In many respects, it was refreshing and stood out positively from the lukewarm and uninspired addresses of the past two decades.

As expected at Munich, he focused on foreign and security policy, European cohesion and transatlantic relations. Notably, he projected a new European self-confidence and asserted German leadership in defense efforts. This inspires hope.

As a more assertive European voice, however, he felt compelled to place blame on the United States for fissures in transatlantic relations and NATO. While the current administration in Washington has brought these fissures to the surface, their roots go back much further, and to European lethargy.

From comfort to responsibility

For decades, transatlantic relations were solid but taken for granted. Europe was comfortable being defended by the U.S. in an arrangement that implied American leadership and a European junior role. That dynamic has changed. The U.S. is no longer willing to bear the full burden, particularly as it pivots toward the strategic challenge posed by China in the Indo-Pacific.

Some 60 years ago, French General Charles de Gaulle called for European military and foreign policy sovereignty, stronger coordination among European armed forces and a distinct European global policy. He was belittled and labeled anti-American. That was inaccurate. He wanted Europe to master its own destiny – complementing, not opposing, the U.S.

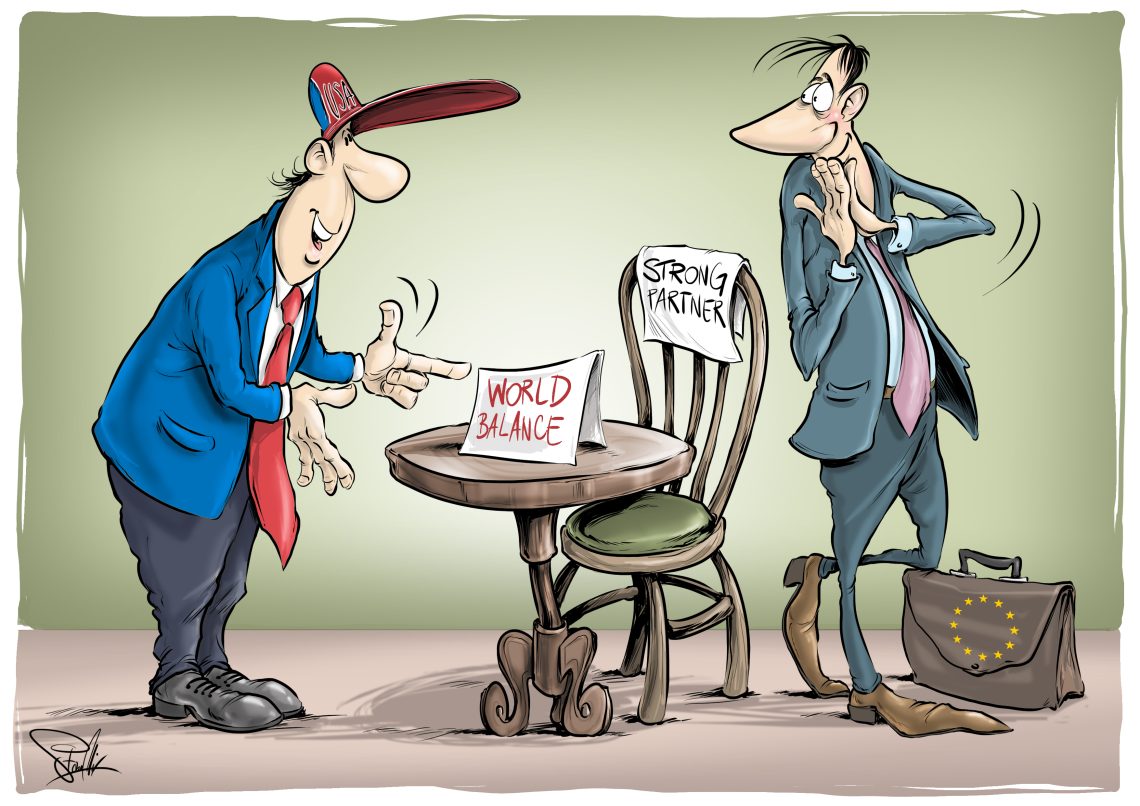

From Washington’s perspective, Europe should be a strong NATO partner, capable of ensuring deterrence on the continent. This requires not only military strength but also a political and economic climate that safeguards Western values and preserves the foundations that once made Europe strong.

Washington’s message: Strength, not sentiment

The Trump administration is not anti-European. It has, however, lost confidence – partly for understandable reasons – in European national institutions and particularly in Brussels, which many in Washington see as unreliable and insufficiently responsive. Previous U.S. administrations failed to address this candidly, and at times contributed to weakening European unity. But Europe’s weakening has also been self-inflicted, driven by protectionist policies in major Western states (including Germany and France), as well as political expediency and a lack of courage.

A clear message came from Vice President JD Vance in Munich one year ago. He did what Europeans have long considered their prerogative: admonish other countries for their shortcomings. That message hurt. It triggered outrage across Europe. Yet the truth often hurts. Among other issues, he pointed to failures in migration control and concerns about freedom of opinion and speech. These are sensitive problems, but the failure to sufficiently confront them has undermined European cohesion and rule of law.

A growing number of Germans, for example, report hesitating to express political views openly or criticize government policy. That is dangerous for a free and democratic society. Uncontrolled migration, meanwhile, has become a dominant issue in internal security and erodes public trust in governing elites. His speech was the first, though perhaps not the most diplomatic, appeal for Europe to become stronger.

In Davos this January, President Donald Trump reiterated that a strong Europe would be the best partner for the U.S. In his characteristic style, he expressed affection for Europe while urging it to become “adult” and address its own structural weaknesses. That message pushed many Europeans out of their comfort zone.

Europeans now lament the erosion of the so-called rule-based liberal world order and blame the Trump administration. But two realities are often overlooked: Any global order requires a hegemon capable of enforcing it – and strong partners to support it. Europe did not consistently assume the role of a strong partner.

At this year’s Munich conference, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio delivered a clear transatlantic appeal. He emphasized the shared heritage of Europe and America and warned that the principles of individual freedom and human dignity are under threat. Europe, he argued, must do its share to defend this legacy.

He also stressed that the common ground between Europe and America is rooted in the European Christian heritage. For Europe in particular, this heritage forms the foundation linking its diverse nations. The Christian legacy indeed protects human dignity and enables the separation of state and religion. This principle has not always been respected, but it remains fundamental.

I have been a convinced European since childhood. I want a strong, free and prosperous Europe – achievable only through cooperation among sovereign nations. My criticism is meant to strengthen, not weaken.

If Americans highlight European deficiencies, the response should not be indignation but determination to improve and become stronger. The U.S. has its own weaknesses. The difference is that Europe is currently losing ground in global competition. American criticism often aims to encourage reform, whereas European responses too often seek to diminish the U.S. to conceal Europe’s own shortcomings.

Europe’s structural weaknesses

Munich was not the forum for a detailed discussion of the economic foundations required to sustain ambitious defense projects. Unfortunately, the German government’s actions so far have not been convincing. German industry faces some of the highest energy costs in the world, excessive regulation, heavy bureaucracy, shortages of skilled labor and a byzantine tax system. An oversized public administration weighs heavily on the economy, while meaningful reductions in headcount or excessive social spending are not envisaged by the coalition.

These problems were not created by markets but by political failure. The planned strengthening of defense will be financed through additional debt. Nevertheless, increasing military deterrence is unavoidable.

The decisive question is whether Europe will return to less state intervention and more market orientation – mobilizing private capital, increasing productivity and restoring competitiveness. The private sector will require more freedom and less state intervention to lead an economic recovery.

If we set aside some of Chancellor Merz’s unnecessary populist remarks against the present administration in Washington and the U.S. position in the world, as well as some tonality on the American side, there are solid foundations for a healthy transatlantic reset.

The ball is in Europe’s court.