Wealth inequality: Causes and political responses

Increasing inequality is a hot topic in many developed countries, especially among younger generations. Many have suggested that higher tax rates at the top income level would solve the problem. French economist Thomas Piketty, for example, advocates for this solution not necessarily because it would increase government revenue and redistribute income, but primarily because prohibitively high tax rates at the top would prevent incomes from rising above a socially acceptable level in the first place.

However, before considering solutions, the primary drivers of inequality must be correctly identified.

Monetary policy and inflation as key drivers of wealth inequality

Generally, central banks around the world want to keep the average annual inflation rate at about 2 percent over the medium term. Official inflation measures, like the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) in Europe, focus only on goods and services that fall into the category of present private consumption. As long as consumer price inflation remains moderate, central banks can engage in accommodative policies and expand the money supply to further other policy goals such as financial stability and employment.

Central banks can continue to expand the money stock despite excessive inflation in real estate and stock markets, for example, if consumer price inflation remains roughly on target. This is exactly what happened in recent decades in many developed countries.

European countries illustrate the point, and the United States and Japan exhibit the same overall pattern (with certain features particular to each country). In Japan, for example, many of the dynamics that we see right now in Europe played out back in the 1980s and 1990s.

The countries of the eurozone have seen overproportionate asset price inflation to varying degrees and at different times. But it hit all of them eventually over the past two and a half decades, as monetary policy became more and more accommodative. Europe has gone from the dotcom bubble to financial crises, to a sovereign debt crisis and a migration crisis. Only when consumer price inflation rose significantly during the second half of the Covid-19 pandemic and amid the outbreak of the war in Ukraine did central banks hit the brakes. Putting the effects of this monetary expansion in reverse, however, will be far from simple.

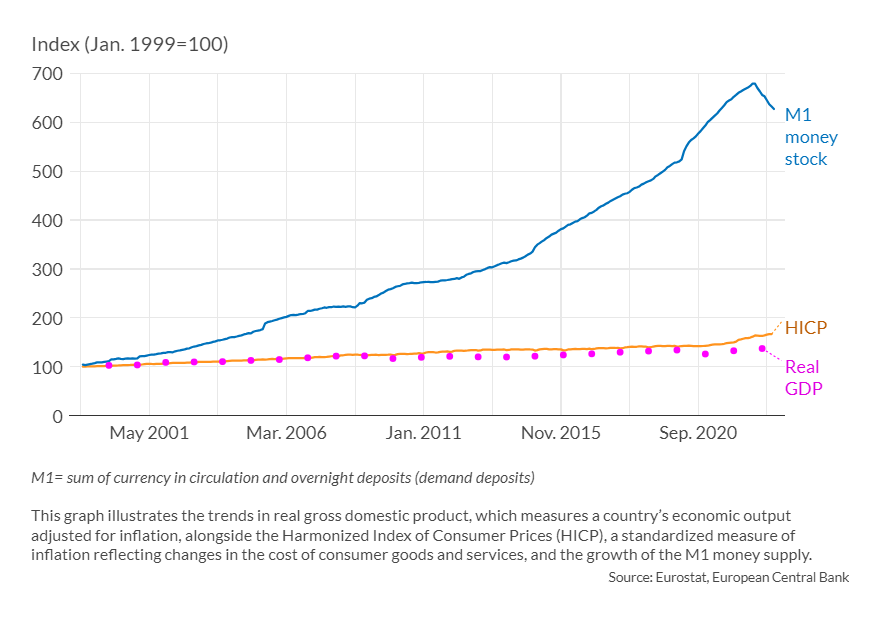

The graph below shows how strongly the European Central Bank has engaged in monetary expansion. The M1 money supply increased from about 1.8 trillion euros in January 1999 to 11.7 trillion euros in August 2022, and then started to decrease as the ECB adjusted its policy.

Facts & figures

From early 1999 to its peak, the average annual growth rate of M1 was 8.2 percent. Such a sustained increase in the money supply can in principle be absorbed either by real economic growth or by increases in the cash-balance demand for money (that is, hoarding), or else it must cause price inflation in some form or another.

Neither consumer price inflation (2 percent annually) nor real economic growth (1.3 percent annually) have been anywhere near the money growth rate. And the entire gap cannot be explained by hoarding. In fact, under inflation, even if moderate at around 2 percent, people face strong incentives to spend their money rather than hang on to it.

The obvious question to ask is: Where did the money go? Part of the answer is that it swept into European asset markets and caused inflation that the official measure does not take into account. The most striking instances of this can be found in real estate markets.

What is M1 money supply?

M1 is a category of money supply that includes the most liquid and readily accessible forms of money in an economy. It typically encompasses physical currency, demand deposits and other checkable deposits. It is a key indicator used by economists and policymakers to assess the liquidity level in the economy.

Since the introduction of the euro in 1999, average house prices in France, for example, have more than doubled. Germany, another major European economy, has experienced a somewhat different pattern in house price inflation. Prior to the financial crisis, house prices stayed constant. Only after the outbreak of the crisis and with the advent of unconventional monetary policies did German real estate prices start to increase. They have since doubled.

To offer another example, Germany’s DAX stock market index has increased by about 4.5 percent annually since the introduction of the euro. During that same period, the German economy has grown only by about 1.2 percent per year in real terms and average consumer price inflation was measured to be about 2 percent per year, including the recent spike.

Such excessive increases in asset prices have direct implications for wealth inequality. The gap between those who own assets and those who do not, especially younger generations, is increasing. Households who own asset classes affected by overproportionate inflation benefit from a positive wealth effect and become richer relative to others.

As existing wealth disparities continue to grow, the prospects for climbing the socioeconomic ladder become increasingly challenging, eroding social mobility.

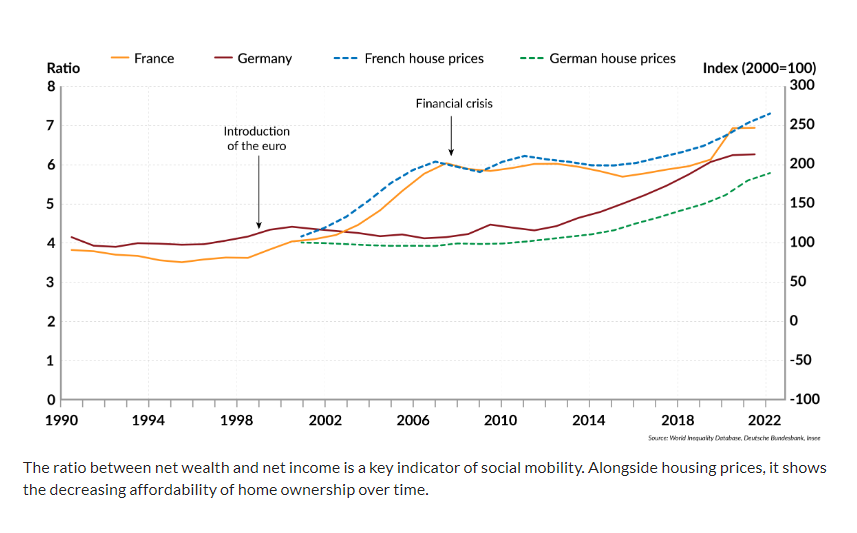

Wealth-to-income ratios are a prominent metric for assessing social mobility. The graph below illustrates substantial rises in wealth-to-income ratios in both France and Germany, which are closely connected to increasing house prices.

Facts & figures

Net-wealth to net-income ratio and housing prices in Germany and France

When the wealth-to-income ratio rises, it means wealth grows compared to annual income. The higher this ratio, the harder it is to rise up the wealth hierarchy. The higher the ratio, the more years on an average income it takes to attain the average level of wealth.

It is important to note that a rising wealth-to-income ratio does not mean that a country has become richer in real terms. It just shows that the monetary value of wealth has grown relative to annual income. If asset prices increase faster than nominal income, the ratio increases, even if nothing changes in real terms.

Hampered social mobility and its potential for political upheaval

The social groups most affected by these developments are households that do not own assets and are therefore primarily dependent on labor income. This includes many young households without inherited wealth. With a wealth-to-income ratio of 3.5, like in France in the 1990s, a household starting out with no wealth at all, receiving an average income and saving 10 percent per year, would need 35 years to attain average levels of wealth. If the ratio stands at 7 instead, like in France today, it would take 70 years. A household would have to earn either an above-average income or save at a higher rate and consume less to reach the average wealth level.

This partly explains why so many people feel left behind and believe that the system is rigged against them. This phenomenon is already manifest in lower voter participation in elections, especially among younger generations, and the drift to the political extremes in many European countries.

Scenarios

Unlikely scenario: Business as usual

Monetary policy has reacted to the high rates of consumer price inflation in 2022 and 2023. Once consumer price inflation is back on target and the disruptions of Covid policies and the war in Ukraine are overcome, it is conceivable that central banks continue business as usual and nothing much changes in terms of public policy. However, this scenario is unlikely, since the issue of inequality is very much on the public’s mind. If monetary policy becomes expansionary again, it will reinforce the adverse effects outlined above – absent any countervailing measures. Calls for greater equality and fairness would grow even louder, increasing pressure on policymakers.

Likely scenario: Fiscal redistribution

European authorities are preparing a uniform and centralized wealth database for households across Europe. This initiative aims to combat crime. Although the authorities have not explicitly declared their intentions regarding wealth taxation, it remains an obvious strategy for addressing the mounting concerns surrounding inequality. The electorate is more likely to support such fiscal measures when they perceive inequality as fundamentally unjust, which it arguably is when it stems from inflation.

In Germany, for example, there is a law on wealth taxation that has not been applied since the mid-1990s, when the constitutional court ruled that it was unconstitutional because it violated the principle of equality. All asset classes must be taxed equally, otherwise holders of certain assets would enjoy benefits relative to others. A centralized wealth registry would facilitate equal taxation of all asset classes and thus help overcome this constitutional barrier.

Higher wealth taxes can increase government revenue in the short run but are likely to lead to dampening real economic effects and lower government revenue over the medium to long run. They create strong incentives to relocate wealth. As the capital stock shrinks (or grows at a lower rate) due to disinvestment, real wages will tend to fall (or grow at a lower rate), ultimately harming the most vulnerable strata of society. Long-run increases in the level of real wages and the overall standard of living are only made possible through sustained investments in the capital stock. Wealth taxation would hamper that process. This scenario is nonetheless likely because policymakers suffer from a short-term bias.

Very unlikely scenario: Monetary policy reform

Another possible response is a substantial policy reform to end inflationary monetary policies. One could envision an economy with moderate rates of price deflation as a natural effect of economic growth. However, the overall short-to-medium-term costs of adjusting to such a regime change are likely deemed too high. A substantial liquidation crisis would be unavoidable. Political incentives do not align well with this possibility.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/wealth-inequality/