The public debt dilemma: Between a rock

and a hard place

Earlier in 2024, global government debt hit a record $91.4 trillion, according to the Institute of International Finance, the global association of the financial industry. The world’s combined gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024 is projected to be approximately $109.5 trillion.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which promotes global monetary cooperation, financial stability and economic growth, has been increasingly vocal in its warnings about the ballooning public debt. Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s managing director, in April shared her fears that the current decade could be remembered as “the turbulent 20s” of this century due to the sobering reality of weak global economic activity by historical standards, along with the debt.

Economic growth prospects have been steadily declining since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, with inflation remaining a persistent issue, fiscal buffers exhausted and rising debt levels posing significant challenges to public finances in numerous countries.

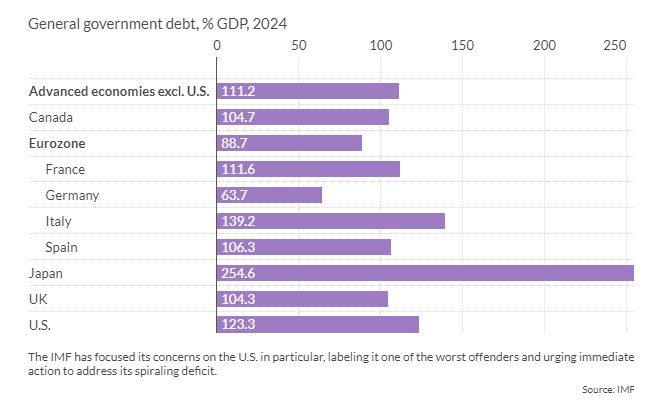

A bad example from the leading country

The IMF has focused its concerns on the United States in particular, labeling it one of the worst offenders and urging immediate action to address its spiraling deficit. Halfway into 2024, the nation’s government debt hit a new $35 trillion landmark, equal to the combined GDP of China, Japan, Germany, India and the United Kingdom. It is projected that by 2032, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio will surpass 140 percent under current policies.

Facts & figures

Part of a broader debt problem

Government debt is part of a larger global debt pile that reached $315 trillion by mid-2024, exceeding the world’s combined GDP by more than two and a half times. This massive burden is spread across households, businesses and governments. Global debt breakdown by sector:

• Household debt: $59.1 trillion

• Non-financial corporate debt: $94.1 trillion

• Government debt: $91.4 trillion

• Financial sector debt: $70.4 trillion

Mature markets hold nearly double the amount of debt across all sectors compared to emerging markets. The U.S. and Japan are the biggest contributors to the global debt pile.

Despite frequent warnings from institutional leaders, politicians and conservative commentators about the dangers of rising public debt levels, next to nothing is being done to actually address the problem. Alarmingly, no meaningful cuts in public spending are even on the horizon. There appears to be no immediate incentive for change, as voters and taxpayers vastly underestimate the direct threat that government debt poses to their lives.

Dangerous mispercentions

Too many people mistakenly assume that high levels of public debt do not impact their personal interests, financial situations or overall quality of life. Excessive government borrowing to finance spending programs fails to ignite public alarm or mobilize protests. Actually, historical trends show that the opposite policy – cutting government spending – most often provokes angry citizen reactions. In the U.S., concerns about public debt are not among the top priorities for voters in the current presidential election campaign. In late July 2024, a Statista report revealed that only 4 percent of the U.S. electorate considered it a vital issue in this election cycle.

Facts & figures

Given that only a tiny fraction of U.S. voters pay attention to government debt, politicians have scarce incentive to address the runaway problem. Reining in debt of this magnitude would necessitate short-term but drastic sacrifices on the part of the public, who primarily perceive the problem as someone else’s concern. Government officials tend to view debt as a hot potato issue that future administrations will handle. At the same time, citizens discount it as a burden that will be foisted on to the next generation. This lack of urgency and accountability perpetuates the cycle of rising indebtedness, leaving little political room for meaningful fiscal reform.

Dramatically reducing government spending is an effective remedy, but wildly unpopular – and for good reason.

This apparent consensus between the government and the public is based on a misunderstanding of the facts. On a fundamental level, higher government debt, and therefore higher servicing costs, translate into less money for public services. That alone directly impacts citizens’ quality of life. Dramatically reducing government spending in areas like public healthcare, education and military budgets or scrapping social welfare schemes are clear and effective remedies, but they are also wildly unpopular – and for good reason.

The shadow of instability

Implementing such cuts at the necessary scale would exacerbate inequality and inflict financial hardship on many households reliant on state support, at least in the short to medium term. A policy U-turn of this magnitude would destabilize the political landscape, given that most advanced economies are by now addicted to higher public spending.

Implementing austerity measures in today’s inflationary climate, as people are increasingly struggling to make ends meet, could be extremely risky politically. During the European debt crisis in the late 2000s, several EU member states were pressured to implement radical austerity measures as a condition for bailout loans. The reaction in southern European nations like Greece was highly adverse, with widespread protests and social unrest. There were real concerns at the time that the austerity policies could fracture the European Union project. Those memories are still fresh, it appears, as any mention of fiscal responsibility these days meets with alarm and extreme resistance, barring a few countries that are trying to mitigate past overspending.

Brussels’ new response to looming debt

Under such circumstances, in April 2024, the European Parliament ratified a new set of fiscal rules that the European Council agreed upon last December. This decision followed significant public protests in Brussels at the time. The new regulations mandate that EU governments maintain budget deficits below 3 percent of GDP and public debt below 60 percent of GDP. This is a return to the bloc’s fiscal guidelines set out in 1992 that reappeared in the “fiscal compact” of 2011, enacted after the financial crisis. The targets, however, were ignored and subsequently forgotten by almost all member states.

As a Euronews article highlighted, the updated framework introduces a risk-based categorization of member states into high-, medium- and low-risk groups. Specifically, countries with a public debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 90 percent are required to reduce their debt by 1 percentage point of GDP each year. Meanwhile, those with ratios between 60 percent and 90 percent must cut their debt by 0.5 percentage points annually.

The article, written by Lucie Studnicna, president of the Workers’ Group at the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), highlighted the results of a recent Eurobarometer poll. When asked about their top priorities, citizens point to combating poverty and social exclusion, improving healthcare and creating jobs, she wrote. She also argued that the revised fiscal rules could hinder Europe’s ability to invest in social programs, hospitals and climate action – precisely the areas citizens are demanding more support for.

However, nations cannot indefinitely continue providing what the people are asking for with borrowed money. Denying or dodging the debt bullet is not a viable long-term strategy. The problem will need to be directly acknowledged and addressed sustainably sooner rather than later.

Scenarios

Looking at possible scenarios moving forward, few reasons for optimism emerge, no matter which path present and future political leaders choose.

More likely: Deception and make-believe ‘solutions’

Expect governments to launch policies ostensibly aimed at mitigating the debt issue through monetary “panaceas” that create the illusion of alleviating the burden. In reality, these measures will effectively pass the actual cost directly onto citizens, particularly savers. In other words, this would be a repeat – or, more accurately, an escalation – of the existing “print and spend” policy doom-loop we have been trapped in since the 2008 crisis. Zero and negative interest rates, along with endless quantitative easing (QE), will lead to even higher levels of inflation down the road and achieve nothing more than, at best, delaying the inevitable explosion of the debt bomb for a few more years.

Unlikely but not impossible: Daring political leaders emerge

This scenario refers to leaders determined enough to embrace the bitter pill of heavily reduced government spending and radically higher taxes. Such a leader, economist Javier Milei, recently came to power in the long-depressed and crisis-tired Argentina. In Europe or North America, similar policies would undoubtedly spur public anger and discontent, leading to broader political unrest and potentially even violent upheaval. Most Western societies are already grappling with severe threats to internal cohesion, as citizens are divided on various issues, including cultural tensions, immigration and ongoing military conflicts. One can only imagine the public reaction if inequality were to rise further and how dire the situation would become for countless state-dependent households if they suddenly found themselves without a safety net.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/government-debts-public-spending-trap/