The politicization of research and teaching

Universities are often idealized as neutral spaces of knowledge creation and critical thinking. However, this image has never been entirely accurate, and it is increasingly at odds with reality. Across many disciplines, research agendas and teaching practices are shaped less by open-ended investigation and more by ideological alignment. The politicization of academic life has not occurred through external censorship, but through internal evolution – subtle shifts in institutional culture, funding incentives and intellectual standards.

Two key mechanisms propel this change. The first is the abandonment of Wertfreiheit, or value-freedom, as a guiding academic ideal. The second is the role of tenure in reinforcing ideological uniformity. Taken together, they reveal how politicization has become not an exception but a structural feature of the modern university.

The erosion of value-freedom

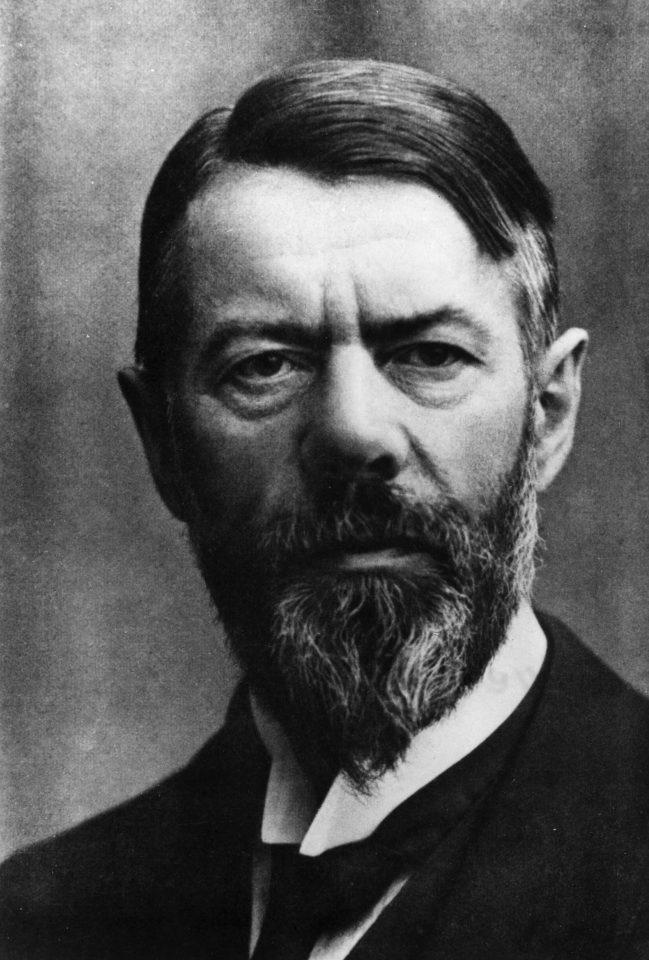

In his 1917 lecture Wissenschaft als Beruf (Science as a Vocation), German sociologist Max Weber formulated what would become one of the central ethical ideals of modern academic life: the principle of Wertfreiheit. According to Weber, the role of the scholar is not to preach, politicize or convert, but to pursue clarity, precision and intellectual discipline. Scientific teaching and research, in his view, must strive to separate empirical inquiry from personal belief.

This does not mean the scholar has no values, but that the lecture hall is not the place to impose them. The ideal of freedom of values is what allows the university to function as a space for reasoned disagreement – a forum where those with different perspectives can confront one another on shared intellectual ground.

Of course, Weber recognized that this ideal could never be perfectly achieved. In practice, research is always influenced to some degree by background assumptions, conceptual frameworks and moral commitments. Even the decision to uphold Wertfreiheit itself involves a value judgment. As Weber put it, one cannot justify the principle of value-freedom in an environment that lacks values. But the impossibility of complete neutrality does not undermine the ideal. On the contrary, the willingness to uphold it as an aspiration is what distinguishes education from indoctrination.

Crucially, not all value judgments are incompatible with academic inquiry. Some values are its precondition. Any honest pursuit of knowledge requires a commitment to truth, clarity, coherence and intellectual integrity. These are epistemic, not political, values – and they are precisely what make pluralism and scholarly dialogue possible. Without them, the search for truth becomes subordinate to asserting personal belief.

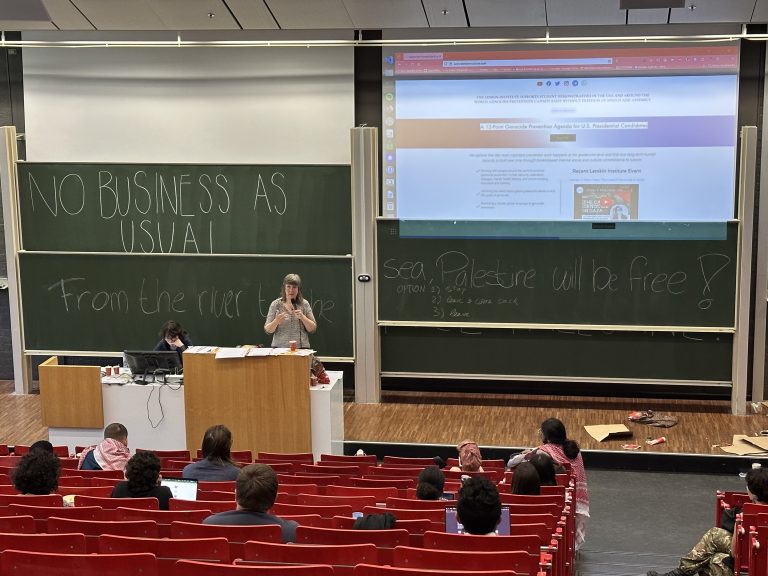

It is this commitment that is weakening in many parts of today’s university. In numerous fields, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, curricula are increasingly framed around activist categories. Concepts such as social justice, decolonization, systemic oppression or climate emergency are not introduced as topics of debate, but as moral foundations on which the course content is built. The student is not invited to evaluate competing explanations but is expected to adopt a given interpretive framework. This is not education in the Weberian sense. It is training in ideological fluency.

Students are taught what to think, not how to think. The university becomes an extension of political culture rather than a check on it.

The erosion of Wertfreiheit is also visible in research funding and publication patterns. Topics that align with dominant political narratives are more likely to receive support, while dissenting perspectives struggle to pass ethical review or peer scrutiny. Scholars quickly learn which questions are “acceptable,” which terms signal virtue and which lines of inquiry invite reputational risk. A culture of self-censorship takes hold, not because people are forbidden to speak, but because the costs of deviation are quietly imposed through institutional channels.

To be clear, none of this requires conspiracy or ill intent. It is the cumulative effect of what Weber might have called the “internal morality” of the profession being displaced by external agendas. The university, instead of providing space for conflict between ideas, increasingly curates acceptable narratives in advance. Debate still happens, but mostly within the boundaries of a relatively narrow moral consensus. Disagreement is tolerated only so long as it does not challenge the foundational assumptions.

In such a context, education loses its transformative potential. Students are taught what to think, not how to think. The university becomes an extension of political culture rather than a check on it. And the principle of Wertfreiheit, already imperfect in practice, is dismissed entirely in theory. What remains is not a place of open inquiry, but a system of credentialing aligned with a specific worldview.

If the erosion of value-freedom marks the intellectual drift of the university, the institution of tenure has become the structural mechanism that sustains it.

Tenure and the institutionalization of ideological conformity

Tenure was once seen as a pillar of academic freedom, a safeguard that allowed scholars to pursue controversial ideas without fear of dismissal or external interference. The principle behind it is straightforward and, in theory, admirable: Scholars protected from political and administrative pressure will be better positioned to speak truth to power, follow the evidence wherever it leads and resist intellectual fashions. But in today’s universities, this logic has been inverted. Instead of championing unconventional views and academic risk-taking, tenure often reinforces established norms. Rather than creating space for dissent, it insulates prevailing ideologies from scrutiny.

The shift is partly structural. In many disciplines, especially in the humanities and social sciences, departments have become ideologically uniform. Hiring committees replicate themselves, selecting candidates who align with the prevailing beliefs of their own members. Once faculty members achieve tenure, they enjoy lifetime job security and near-total autonomy over their teaching and research.

In principle, this could allow for great intellectual diversity. In practice, it often leads to entrenched political and theoretical conformity that goes unchallenged. Tenure no longer functions as a shield for free inquiry. It protects the internal consensus. When job security is nearly absolute and professional turnover is low, faculty have a strong incentive to prioritize like-mindedness in hiring decisions. A dissenting or unpredictable colleague is not just a potential short-term disruption; they become a permanent presence within the department.

As a result, tenure promotes not only intellectual entrenchment but also social self-selection, where ideological homogeneity is seen as the safest long-term investment. Once established, this soft consensus becomes increasingly difficult to challenge from within.

The system designed to encourage bold thinking instead promotes conformity and silence.

This dynamic is compounded by institutional incentives. Universities are increasingly governed by reputational concerns, funding metrics and external pressures from accreditation bodies and activist groups. Risk aversion dominates in this climate. Administrators are unlikely to challenge tenured faculty, even when concerns are raised about political bias in the classroom or the suppression of competing perspectives. Students, too, may hesitate to voice disagreement in settings where certain views are presented not as positions in a debate, but as moral imperatives. Tenure, originally a tool to defend academic integrity, now often enables a culture of ideological impunity.

The effects ripple outward. Younger academics, particularly those on temporary contracts or in precarious positions, quickly learn which views are safe and which are career-ending. The early stages of academic development, from PhD supervision to postdoctoral mentorship, are shaped by a hierarchy that rewards adherence to prevailing norms. Intellectual innovation, especially of a non-traditional nature, becomes risky. The system designed to encourage bold thinking instead promotes conformity and silence.

This is not to say that every tenured professor uses their position to push ideology, or that all departments are politically uniform. But the structural incentives make ideological drift more likely and more difficult to reverse. Without meaningful accountability, whether from within the institution or from external stakeholders, tenure becomes less a protector of Wertfreiheit and more a mechanism by which its erosion is perpetuated.

Ultimately, the tenure system reflects a deeper paradox in modern academia: The mechanisms designed to preserve freedom of thought can, under certain conditions, become obstacles to it. When the moral purpose of the university is assumed rather than contested, and when institutional protections are used to entrench that assumption, politicization becomes not a deviation from the norm but the norm itself. And reform, no matter how urgent, becomes exceedingly difficult.

Scenarios

The politicization of research and teaching will not disappear overnight. But how it evolves and whether universities can restore their commitment to open inquiry depend on a mix of internal pressures and external responses.

Likely: Further ideological entrenchment

Universities continue on their present path. Curricula become more uniform, with moral frameworks treated as unquestionable truths. Tenured faculty face no pressure to diversify intellectual content, and dissenting voices are further marginalized. Research funding remains tied to ideological conformity, reinforcing selective inquiry.

Public trust erodes further, but internal reform remains unlikely. The university becomes a semi-insulated moral institution, offering degrees in cultural alignment rather than critical thinking. The likelihood of this scenario is 50 percent.

Somewhat likely: Institutional pluralism emerges

As frustration with academic orthodoxy almost inevitably grows, new institutions and platforms arise – private universities, liberal arts colleges, independent research centers and online academies – explicitly dedicated to intellectual pluralism and academic rigor.

These alternatives begin attracting students, faculty and funding. Some traditional universities respond by relaxing ideological controls and restoring Weberian principles of value-freedom.

Others double down. A fragmented but dynamic academic landscape begins to take shape with meaningful competition and self-correction. The only hurdle standing in the way of this scenario is government regulation and funding, making the emergence of alternative institutions more costly and difficult. The likelihood of this scenario is 35 percent.

Unlikely: Structural reform

Mounting external pressure from employers, alumni, government bodies and the general public pushes mainstream universities to reform their internal governance structures. Tenure is restructured or limited in scope. Hiring and funding practices are opened to ideological diversity. Departments are expected to demonstrate viewpoint pluralism and transparency.

While difficult to implement, these reforms gradually restore trust in the university as a space for genuine education and research. The principle of Wertfreiheit, once thought obsolete, reemerges as a foundational guide.

This scenario is less likely because pressures for existing universities to make the necessary reforms will likely require the emergence of competing, alternative institutions in higher education and research. The force of competition is far more promising than any other external pressure. The likelihood of this scenario is 15 percent.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/politicization-of-universities/