Ten years without Juan Carlos Cachanosky

Last December 31, 2025, marked the 10th anniversary of Juan Carlos (“Charly”) Cachanosky’s (JCC) early passing. After a decade, his absence is still felt, not only in personal lives but among free-market scholars throughout Argentina and Latin America.

I’m frequently asked how I got into economics and interested in the unconventional Austrian school. “Family business” is my quick reply. But, of course, there is a story. In mid-high school, we were assigned to come up with a topic suitable for a debate for our Spanish course. Interested in physics at the time, I struggled to find a suitable topic. So, I took the opportunity to ask him an economics question and learn a little more about what his work was about. There was this issue I took from our history course discussion of the industrial revolution that didn’t fit right with me, but I couldn’t explain why: That technological advancement (“machines”) produces unemployment. Something was off. How was it possible that more productivity results in more poverty instead of more wealth? Over lunch at one of our regular weekend restaurants, I asked him to explain this to me. He took a paper napkin from the table, and using a pen he always carried with him, he laid out a step-by-step process, just using a simple table, showing the effects of new technology on employment and income. The conclusion that new technology doesn’t create aggregate unemployment confirmed my suspicion. It was the clarity and force of the explanation that left a lasting impression. Economics wasn’t just smart guessing about social events; there was a “science” behind a phenomenon where the object of study has purposeful action. The economics “apple” decides when, in which direction, and at which speed to fall. How can you do science with this? My interest quickly shifted as he would guide me through readings by Gary Becker, Friedrich Hayek, Henry Hazlitt, and Karl Popper. In my mind, economics became the difficult science because of this extra challenge. Soon after, I decided to pursue a degree in economics instead of physics.

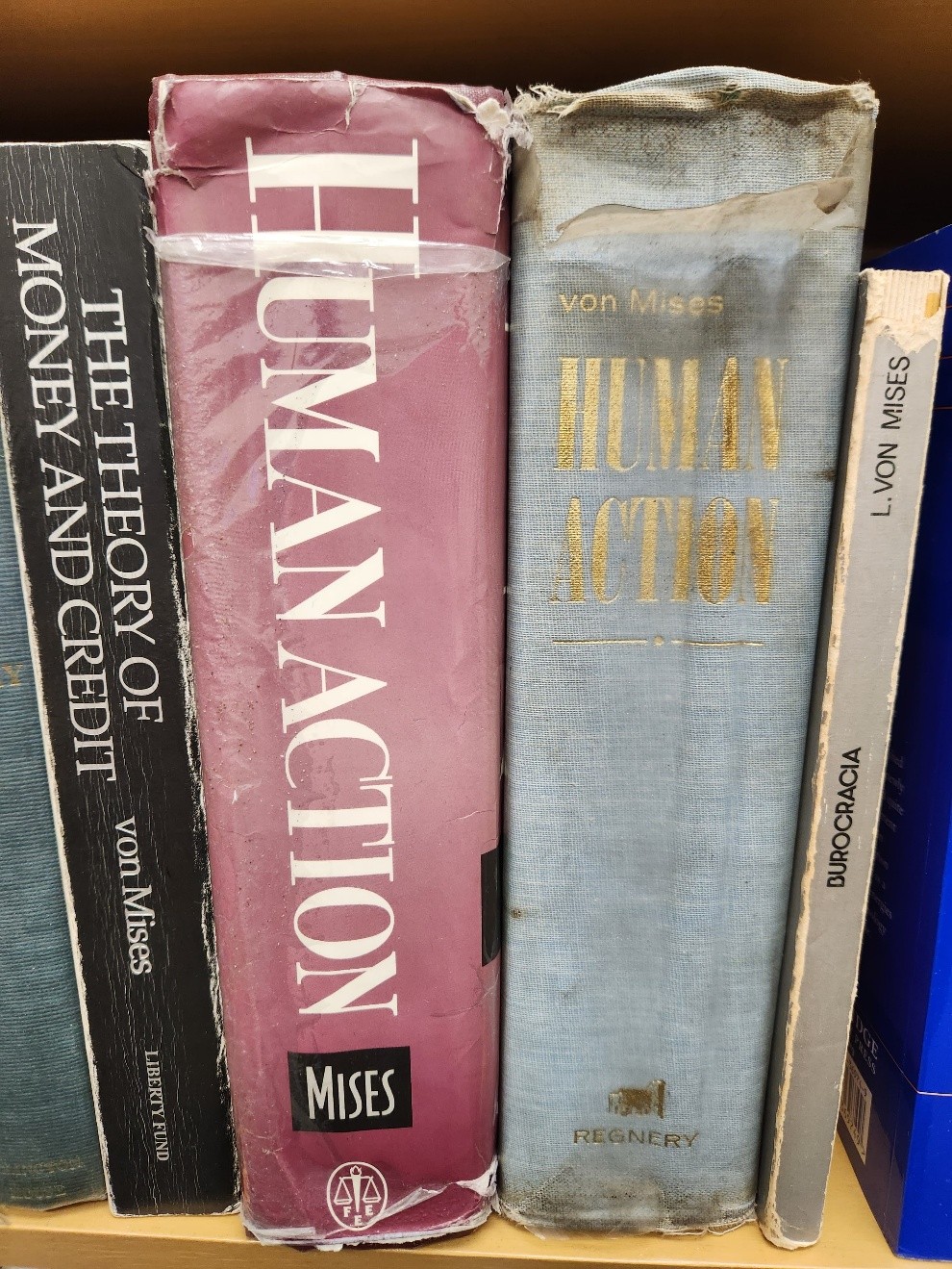

Once I told him my career decision, he made an extraordinary detour. On a flight back from Europe, he had a connection in New York. During the layover, he took a taxi all the way to Irvington-on-Hudson, the historical location of the Foundation for Economic Education before it moved to Atlanta, GA. He purchased the “FEE version” of Mises’s Human Action, took a taxi back. As soon as he arrived home, he presented me with this gift shortly before starting college. I read Human Action every summer break for six years in a row after that. Today, his copy and my copy of Human Action stand next to each other on my bookshelf. This extra mile for “just a book” is just an example of how his natural generosity would have a long-term impact on others.

Beyond being my father, he was a rigorous scholar whose work remains essential to economics today. When Paul Krugman won the Nobel Prize in 2008, he immediately noted the prize was well deserved for Krugman’s contributions to international trade, free-market oriented or not. Contrary to some misconceptions, Austrian economics does not have to be dogmatic, of which he was a living proof. While I cannot address all his academic contributions, three stand out for their continuing relevance.

First, his doctoral dissertation on the pitfalls of mathematical formalism in economics. Written in the early 1980s, it remains the most profound and detailed analysis of the subject I’m aware of, far more precise than most Austrian critiques that still circulate today. Crucially, his argument wasn’t against mathematics in economics, but against how it has been applied. Even with today’s dominance of DSGE models and dynamic optimization, his insights remain relevant. For instance, he correctly identified that the problem with utility functions isn’t that they measure utility (they don’t), but the confusion between pragmatic continuous treatment of utility versus the precision of discrete utility, a distinction many critics of mathematical economics still miss.

How did he arrive at this topic? The story comes from those who knew him back then, and while I cannot verify every detail, here’s how it’s remembered: He met Hans Sennholz, a PhD student of Mises, during Sennholz’s visit to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Sennholz initially discouraged him from pursuing a PhD in economics until JCC disclosed his topic: the pitfalls of mathematical formalism. Mises had apparently asked Sennholz to work on this very topic, which Sennholz never pursued. Feeling indebted to his mentor, Sennholz agreed to advise JCC after an impromptu oral exam in front of everyone else at a social gathering. As JCC sent him draft chapters, Sennholz repeatedly replied that he wasn’t “PhD material.” JCC persisted, successfully defending before a panel of mathematics PhDs, and went on to a distinguished career in ESEADE (the “Austrian” graduate school in Argentina) and even became Dean of the Universidad Francisco Marroquín in Guatemala’s business school.

Second, what I call his “second doctoral dissertation”: his two-volume work on the history of theories of value and price. This incredibly detailed study traces how subjective value and price were theorized from Greek philosophers through modern economics, correcting many misconceptions along the way. The clearest correction: the claim that classical economists held a labor theory of value. This is doubly incorrect: the classics had a cost theory of price (not value), and while labor might constitute that cost, it need not be the only component. He also examined the extent to which Spanish scholastics were proto-marginalists or free-market thinkers. His evidence points the other direction: scholastics sought the just price (as opposed to the equilibrium price) to advise the King on justly controlling prices.

Third, his application of corporate finance to economics, particularly the Economic Value Added (EVA) framework, which connects cash flow and capital structure to economic value creation. His paper explaining economic recessions through this framework was illuminating, capturing how real-world economic agents experience economic phenomena. As I approached the end of my undergraduate studies and began thinking about doctoral dissertation topics, he encouraged me to apply the EVA framework to Austrian business cycle theory.

My dissertation, written shortly after the 2008 financial crisis, addressed ABCT but without the EVA framework, as I wasn’t yet sure how to implement it. Soon after graduation, a door opened. At the Society for the Development of Austrian Economics meetings at the Southern Economic Association conference, I heard Roger Koppl state that the average period of production (“roundaboutness”) is the Macaulay duration of a cash flow. I realized I wasn’t alone in thinking along these lines.

I reached out to Koppl and Peter Lewin. Both saw merit in the approach. Just five minutes after his first reply, Lewin reached out again, offering to co-author a paper on this topic. What began as a project I thought might yield three papers (one on the history of thought, one theoretical, one empirical) became a decade-long collaboration producing more than ten papers and two books. Still today, we continue to work on this theme together. This exemplifies why his work remains relevant: good research discovers new paths, even when the original researcher cannot follow them all. A mentor opens paths to his disciples.

During the 1980s and 1990s, he was involved with ESEADE’s journal, LIBERTAS. The journal was discontinued in 2006, replaced by Revista de Instituciones, Ideas y Mercados. His final project was relaunching the journal as LIBERTAS: Segunda Época, with his students and colleagues on the editorial board. Sadly, he didn’t live to see the first issue published. Wenceslao Giménez Bonet, Adrián Ravier, and I took on the duty of keeping it alive, which is one of the many ways his students continue his work. In true reflection of his character, LIBERTAS: Segunda Época remains an outlet friendly to young scholars and anyone interested in classical liberal ideas in general. The journal, which includes an English translation of his paper, has just published its 10th volume.

His final academic work returned to his first passion: mathematics and economics. “Mathematical Problems in the Theory of Price” was half-finished when he passed. I took on the task of completing it and included it in the first volume of LIBERTAS: Segunda Época as the first and last Cachanosky & Cachanosky paper.

JCC was not a spotlight person, and there are not many pictures of him. The last one I share is special for this outlet, as it was taken at one of his visits to ECAEF, a trip he always enjoyed, as his relaxed smile clearly shows.

Ten years on, his contributions remain relevant to Austrian economics. His critique of mathematical formalism remains relevant today. His historical work corrects errors that still circulate. And his corporate finance applications opened pathways that continue to bear fruit. Austrian economics is not just richer for his work, it is more rigorous, more applicable, and better equipped to address real-world phenomena. His scholarship and mentorship are the legacy he leaves behind.