Regulation and fiscal drift threaten

Western prosperity

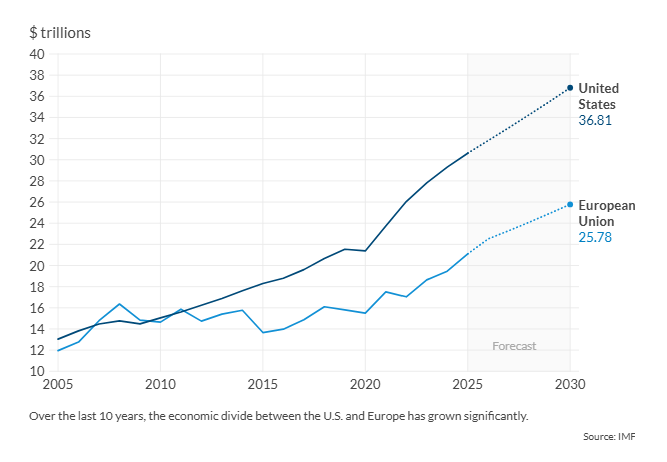

Over the past decade, the economic gap between the United States and the European Union has widened. What was once a slow divergence has accelerated since the pandemic, as growth, productivity and investment increasingly favor the U.S. This gap is more than a statistical curiosity; it reflects a deepening divide in policy orientation and economic dynamism.

Pandemic-era emergency programs were never fully rolled back. Instead, Western governments layered new spending commitments on top of already swollen budgets, while accumulating new regulations and reporting requirements on energy markets, technology innovation and industry. Inflation and higher interest rates then turned once-cheap debt into a growing burden, exposing the limits of fiscal and regulatory expansion.

The result is a closing vice: Regulatory accumulation and shrinking fiscal space now squeeze the productive economy.

Economic divergence

Between 2015 and 2024, U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged roughly 2.5 percent annually, whereas Europe averaged closer to 1.7 percent, about two-thirds of the U.S. rate. The gap in productivity growth has also widened. The U.S. labor productivity growth rate was 1.3 percent per year over the same period; Europe averaged 0.7 percent. These numbers reflect long-standing structural differences, but the post-Covid era has made them more pronounced. The U.S. real GDP level in 2024 was approximately 24 percent higher than its three-decade pre-pandemic trend, while the eurozone’s output remains 20 percent below trend.

Facts & figures: GDP growth: U.S. vs the EU

These differences are not trivial. Slower growth today means lower living standards tomorrow, fewer medical breakthroughs, reduced economic mobility for workers and families and a narrower opportunity set for the next generation. The gains of the past century were built on sustained productivity growth. When growth falters, those trajectories flatten, and it becomes harder to finance innovation and absorb shocks.

Countries in the West generally remain desirable places to live and will likely remain so for some time, even as growth slows. However, high living standards today cannot mask structural economic problems forever. As economist Tyler Cowen observes, Europe is already losing influence as it stagnates economically and culturally. Without serious reform, the rest of the West, including the U.S., may follow in Europe’s footsteps.

One structural reason Europe is falling behind is regulatory accumulation, which acts as a brake on innovation and competitiveness.

Regulatory burden

One structural reason Europe is falling behind is regulatory accumulation, which acts as a brake on innovation and competitiveness.

The numbers tell the story. Between 2019 and 2024, the EU adopted over 13,000 legislative acts, compared to just 3,500 at the U.S. federal level. By this crude measure, Europe is passing almost four times as many new rules annually as the U.S. The EU also has a higher prevalence of non-tariff barriers than the U.S., suggesting much more extensive use of regulatory management of the economy.

Sustainability reporting is particularly burdensome. Most EU-based companies must comply with a web of overlapping rules. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Europe report high compliance costs, with almost a third dedicating more than 10 percent of their staff to compliance. Many suppliers have also added as many as three full-time employees solely to manage sustainability-related data collection. Surveys of business sentiment reinforce the point: Two-thirds of EU companies view regulation as a barrier to long-term investment. In the U.S., comparable surveys report that only 20 percent of firms consider regulation a major barrier. That is a striking difference.

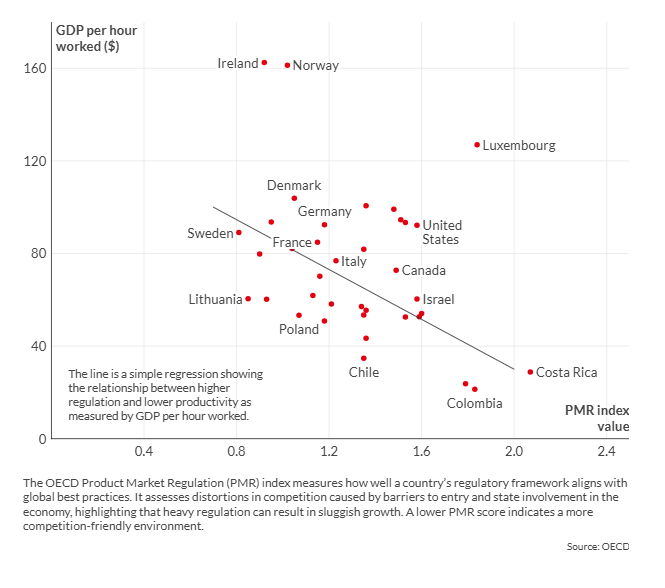

Other indicators reinforce the stakes. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Product Market Regulation (PMR) index shows a clear, negative link between regulatory restrictiveness, productivity and GDP. The PMR index does not capture all regulatory burdens, particularly those on labor and the environment. Even modest declines on this narrow measure of regulatory efficiency can compound into significant long-term growth losses. This should serve as a warning for policymakers across advanced economies, regardless of small differences in rankings or measurement approaches.

Facts & figures: GDP per hour worked and the Product Market Regulation index

While Europe discusses competitiveness, the U.S. is acting on it. The EU’s latest effort (most prominently in Mario Draghi’s report on “The future of European competitiveness”) lays out an ambitious reform agenda but remains largely diagnostic and declaratory rather than operational. Brussels continues to produce reports and communiques, while its regulatory machinery continues unabated.

By contrast, the U.S. has already begun translating diagnosis into action. Under Executive Order 14192, Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation, the Trump administration has directed agencies to eliminate at least 10 regulations for every new one adopted. It has also moved to accelerate environmental permitting, energy-project approvals and other long-delayed reforms to reduce compliance bottlenecks.

The irony is that Europe faces a more acute competitiveness problem, yet it remains stuck in the consultation phase. The American approach is imperfect and evolving, but it at least reflects a governing philosophy of removing friction, not just cataloging it.

Fiscal policy challenges

Beyond regulatory drag, fiscal pressures are tightening as pandemic-era programs linger and new spending commitments accumulate, just as higher interest rates and defense demands compound budgetary strains.

The International Monetary Fund forecasts that the net debt-to-GDP ratio among advanced economies will increase by about 10 percentage points by 2030, reaching 90 percent. This threshold exceeds the point at which economists have identified that debt begins to measurably drag down economic growth.

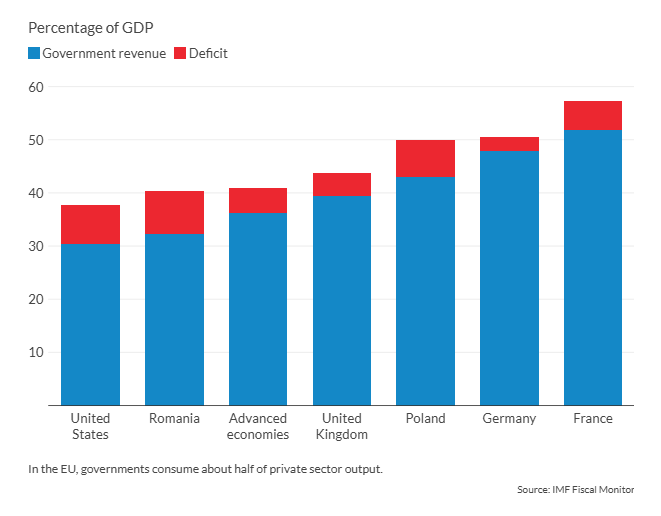

Yet the fiscal picture is not uniform. The U.S. still benefits from higher growth and reserve currency advantages, although its entitlement program spending commitments are unsustainable. Many European economies, such as France, combine high taxes with weak productivity growth, leaving little room for unexpected fiscal demands.

Others, like Poland, are only now confronting the costs of rapid program expansion, which is being layered on top of demographic headwinds. The United Kingdom sits somewhere in the middle, caught between a desire to chart a post-EU course and a persistent inability to follow through on reform. Across these cases, the pattern is clear: Governments are spending faster than their economies can grow, testing the limits of fiscal sustainability.

Facts & figures: Government revenue and deficit as a percentage of GDP, 2025

France typifies the Western dilemma. With public spending regularly more than 55 percent of GDP and budget deficits around 5 percent, fiscal pressures fuel volatile politics. Pension reform efforts sparked massive protests in 2023 when the retirement age was moved from 62 to 64. The inability to pursue stable reforms to the country’s fiscal system leaves leaders with few options. France’s tax burden on average workers exceeds 53 percent, the highest among OECD countries. Novel proposals for higher digital taxes, levies on foreign income and wealth taxes are all illusory fixes that will do more damage to France’s medium-term tax base, making the problem worse, not better.

Poland

Poland’s trajectory shows how quickly fiscal momentum can reverse. Following post-communist liberalization and EU accession reforms, Poland experienced a prolonged period of strong growth and prudent budgeting. The general government deficit fell to less than half a percent of GDP by 2018, and debt remained comfortably below 50 percent of GDP. But in the last several years, particularly post-pandemic, fiscal discipline has loosened amid a clear political shift toward expanded social transfers. The invasion of Ukraine necessitated additional defense spending just as fiscal space was beginning to deteriorate.

Despite strong fundamentals, Poland has taken a late turn into fiscal fragility, with deficits climbing above 6 percent of GDP, even as economic growth remains relatively high. Poland risks slipping into a higher-tax, lower-growth equilibrium.

United Kingdom

The UK aspired to become a “Singapore-on-Thames” after Brexit but has yet to deliver the regulatory and fiscal reforms needed to diverge from Europe’s growth path. The tax-to-GDP ratio is projected to surpass 40 percent next year (a post-war high), topped by its unfunded 4 percent of GDP deficit. Most EU rules remain on the books, planning and infrastructure barriers continue to hold back investment (which remains among the weakest in the OECD), core public services show signs of strain and productivity growth has stagnated since 2008. British policymakers learned the wrong lessons from the 2022 gilt-market crisis, turning to tax threshold freezes and corporate tax increases that reinforce the punishing high-tax, low-growth dynamic.

United States

The U.S. has an extraordinary (and extraordinarily dangerous) fiscal capacity, thanks to the dollar’s status as a reserve currency and deep capital markets, but its long-term fiscal trajectory is no less perilous. Healthcare and retirement entitlements, together with rising debt-service costs, account for nearly all projected debt growth. In 2025, the federal budget deficit was $1.8 trillion – a whopping 6 percent of GDP − and renewed tax cuts could push annual deficits above $3 trillion within a decade.

Disregard for fiscal sustainability, paired with political shifts toward protectionism and state-directed industrial policy, risks undermining the very dynamism that sustains U.S. fiscal resilience. If growth slows or interest rates rise, fiscal margins will shrink even more quickly. The near-term risk is not an immediate funding crisis but a creeping one: Ever-higher taxes to finance entitlements and interest expense will gradually erode the U.S.’s competitive edge.

Scenarios

Least likely: Consolidation and renewal

Governments commit to reducing spending-to-GDP through expenditure cuts and entitlement recalibration. Tax policy pivots from rate hikes to base-broadening and investment-friendly design. Regulatory policy shifts in favor of removing rather than adding new rules, speeding up permitting and adopting mutual recognition of standards that accept other jurisdictions’ regulations as broadly equivalent. Debt ratios fall, interest burdens ease and private investment deepens.

Most likely: Drift and stagnation

Policymakers lacking leadership and vision keep postponing tough choices. Tax thresholds remain frozen, regulations keep piling up and spending edges higher each year. Debt ratios drift upward and competitiveness erodes. Public services weaken even as budgets grow, feeding more political and societal frustration.

Also very possible: Crisis and forced austerity

A sudden shock, such as a sharp rise in global interest rates or a wider war, forces governments to implement abrupt austerity. Budget cuts and tax hikes are imposed under duress. Countries that emphasize spending restraint can recover through a virtuous cycle of renewed confidence and investment, while those that rely on higher taxes fall into the opposite trap: growth contracts, unemployment rises and strategic capacity in defense and infrastructure erodes.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/us-europe-economic-gap/