Africa shows ESG is near an adapt-or-die moment

The widespread adoption of non-financial standards for assessing economic performance, often called ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) criteria, appears to have had an impact on financial markets, one that is diffuse and hard to measure. The implications of this shift to a rigid yet vague system of evaluation could be especially challenging for African companies and economies, which are highly dependent on capital flows that must now measure up to the demanding ESG yardstick.

In theory, requiring that investors and aid donors pay attention to sustainability could help accelerate innovation in Africa by encouraging recipients to adopt best practices and leapfrog development stages. The risk, however, is that the imposition of a bureaucratic scoring system could also force emerging markets into a directed and centralized form of capitalism – driving up costs, reducing efficiency and ultimately curbing economic growth.

ESG’s beginnings – and decline

ESG has become a buzzword in recent years. The acronym was originally intended to help introduce global standards for sustainable investment by using social impact issues to measure corporate performance and investment risk.

The concept emerged two decades ago in a 2004 letter sent by then United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan to several financial institutions, urging them to adopt environmental, social and governance criteria for evaluating their investments. Two years later, the UN formally launched the Principles for Responsible Investments initiative to incorporate the criteria in financial analysis and decision-making processes.

ESG is a product of global governance theory, which postulates coordination between multiple actors – mainly international organizations, corporations, investment funds and governments – based on norms and principles legitimized by the claim that global challenges and goods transcend individual states. Designed in the late stage of hyper-globalization, ESG applies the “multi-stakeholder” approach to investment devised by theorists of stakeholder capitalism.

Facts & figures

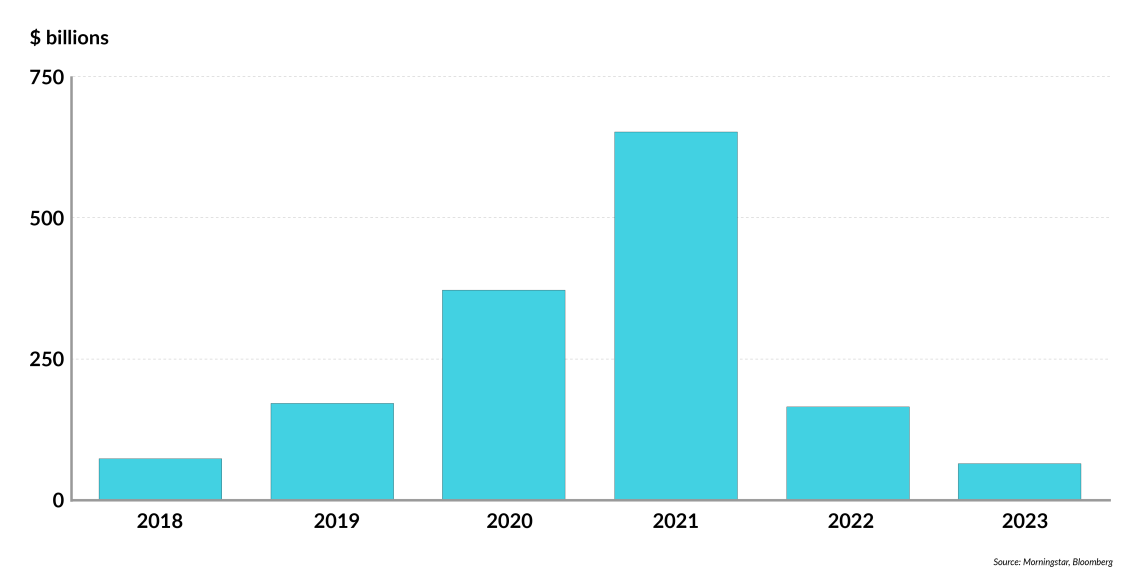

Net flows to ESG funds

Two decades after its dawn, however, ESG may be an idea whose time has come and gone. Its initial spread was accelerated by a combination of factors, including culture wars in the United States, rising climate concerns, low interest rates and, in the latter stages, the Covid-19 pandemic. One measure of its success was the near exponential growth of global ESG assets under management (AUMs), which topped $35 trillion by 2020.

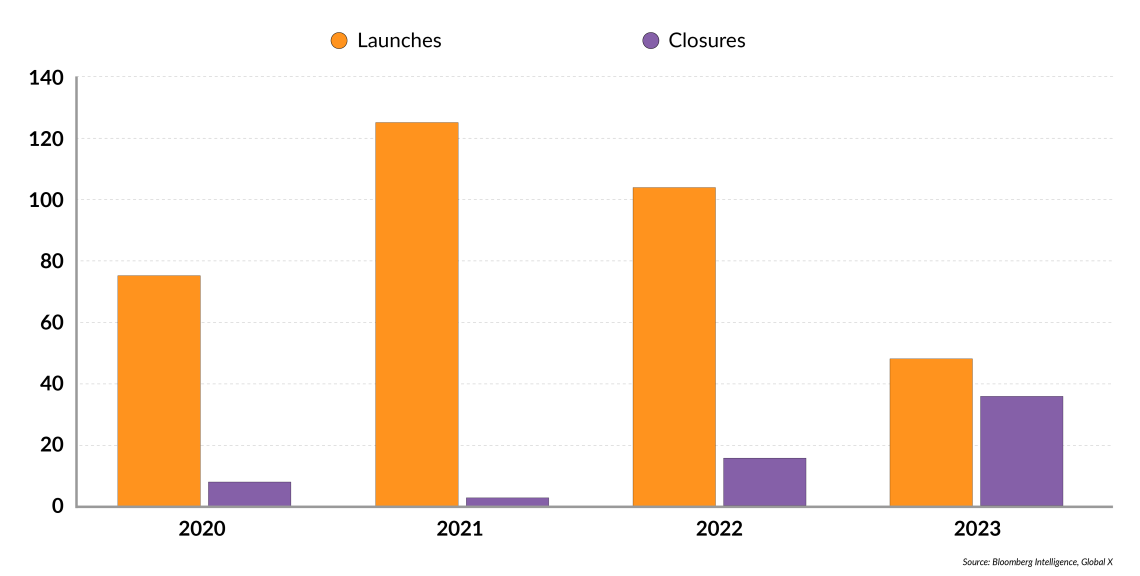

Now, economic and geopolitical trends have decelerated growth in the ESG market; one forecast predicted it would expand at an average annual rate of only 3.5 percent through 2030. There is, however, geographical nuance to this bearish outlook. While the downward trend is clearly visible in the U.S. market, where several ESG funds have closed, Europe still seems firmly committed to the principle.

Facts & figures

ESG ETF launches and closures in the U.S.

ESG’s effects on Africa

To evaluate how ESG may affect African economies, one must consider two basic critiques: performance and legitimacy. The debate over whether ESG investment funds have higher returns than their non-ESG peers continues unabated, but there is little conclusive evidence that higher ESG scores lead to more profit. However, it is undeniable that ESG’s incorporation, compliance and reporting requirements bring more regulation, bureaucracy and higher costs, posing additional challenges to African companies. Also, using ESG criteria to measure performance may serve as a disguise for companies that underperform by other business benchmarks.

Moreover, companies that score well by ESG criteria are not necessarily stakeholder friendly, as ESG funds have been found to more frequently violate labor and environmental laws, and they do not seem to perform better in corporate governance as measured by such criteria as board independence or treatment of employees.

From a strict market perspective, a combination of higher regulatory costs and a lack of measurably higher returns on investment could dent the legitimacy of ESG. The doctrine’s ambitious attribution of social and political functions to markets has also been criticized for relying on relatively vague and debatable concepts subject to varying interpretation by regulators and stakeholders across different cultural and economic contexts.

The difficulty of defining and translating ESG goals into objective criteria also makes the concept vulnerable to distortions and contradictions. One example is the deceptive practice of “greenwashing,” which has become a growing concern across several industries and has special relevance to Africa. As several recent cases have shown, the prevailing energy and food insecurity in poor countries could make complying with sustainability criteria incompatible with ESG standards for social equity, and vice versa.

Mismatched goals

ESG reflects concerns that have come to weigh more heavily on Western agendas but do not always resonate with the expectations and choices made by Africans, who face more urgent challenges. For citizens and entrepreneurs trying to overcome poverty, unemployment, energy and food insecurity, low connectivity and a general lack of infrastructure, adapting to the demands of ESG may seem an unnecessary expense.

Another challenge has to do with the broader impact of ESG-oriented investment, especially through grand initiatives adopted by the European Union. In the latter case, ESG regulations affect not only investment coming from Europe, but also sales by African companies that export to the European market or fall under the definition of “supplier” in goods or services value chains. Initiatives like the European Green Deal can have a positive impact on Africa by offering new opportunities, but can also have the opposite effect by raising obstacles or even protective barriers in key sectors like energy or agribusiness.

A sharp reminder of the contradictions between the “environment,” “social” and “governance” dimensions of ESG is provided by the mushrooming demand for rare earth elements and other energy transition materials. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s copper belt, for example, mining to supply the metals needed for green technologies is raising concerns about environmental damage, corruption, child labor and human rights abuses.

African countries’ differing ESG approaches

Across Africa, significant differences can be observed in how countries and companies have adapted to ESG demands. In South Africa, environmental and social concerns have a strong tradition. The continent’s biggest equity market, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, launched a Socially Responsible Index back in 2004, while the country enacted a Carbon Tax Act in 2019 and increased the levy to 16 percent in 2024. This regulatory environment makes it easier for South Africa to align with the standards set by the EU.

Even so, persistent power outages in South Africa as well as Zimbabwe show that a lack of reliable energy remains a stumbling block to economic growth. It remains debatable whether Indigenization and Black Economic Empowerment legislation, with its recourse to resource and economic nationalism, have delivered better social outcomes for South Africans. Results on the governance dimension are also modest, as corruption and nepotism remain pervasive.

Nigeria, which competes with South Africa for the status of Africa’s top economy, has adopted a different approach. The focus of its 2060 Energy Transition Plan is energy security, setting a goal of net-zero emissions by 2060 through initiating a gradual phase-out of fossil fuels starting in 2030. Recently, the government announced that companies would have four years to adopt eco-friendly reporting standards. Other countries, like Ghana, have started Sustainability Bond programs to finance or re-finance green and social projects. However, these financing schemes are hampered by the complexity of their assessment criteria and cumbersome certification and reporting process.

Scenarios

Most likely: ESG pullback

Under a first, more likely scenario, the current retreat of ESG-oriented investment will continue, as sustainability criteria fail to take off in emerging markets, stagnate in Europe, and keep shrinking from their 2021 peak in the U.S. This could be part of a broader depoliticization of financial markets as a consequence of “green fatigue” and a political environment more skeptical about social engineering. Further geopolitical turmoil will accentuate concerns about security and value chain resilience, to the detriment of ESG concerns. This scenario will also be accelerated by the intensification of geoeconomic competition between different blocs, where regional interests replace the previous global ambitions.

Under this scenario, EU-Africa investments will further decrease. For African companies, European investment would become less attractive due to persistent higher business costs driven by the regulatory framework and ESG demands.

Less likely: ESG recalibrated

Under a less likely scenario, ESG criteria will continue to influence financial markets, signaling the end of the deglobalization (or slowbalization) wave, but still go through a process of recalibration and decentralization. While less likely, several indicators suggest this is also a possible scenario. For one thing, the expanding war in Ukraine has ushered in a grand return of geopolitics and geoeconomics, prompting decisionmakers to take a different view of value chains and energy security around the world. The conflict has also contributed to a more fragmented world, leading to greater acknowledgement that countries may decide on different development trajectories, and lessening enthusiasm for centralized financial solutions as embodied in the top-down ESG approach.

The tremendous disparities across Africa argue for a more decentralized and flexible approach to sustainable investment, which could encourage accelerated, “leapfrog” development while promoting homegrown innovations. Each country or company could set up a different hierarchy of environmental, social and governance criteria, with some prioritizing nature conservation, some focusing on renewable energy projects, and others choosing to delegate energy decisions to individual stakeholders, maximizing local freedom of choice.

From a global market perspective, this recalibration is required by the new high-interest-rate environment, which highlights the costs associated with compliance and reporting, and by internal political changes at the epicenters of the ESG movement – the EU and the U.S.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/africa-esg/