The tyranny of antitrust policy

On March 21, 2024, the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) and 16 state attorneys general announced a broad lawsuit against Apple on antitrust grounds. The suit’s crux lies in Apple’s tight control over the iPhone ecosystem. Apple says this control contributes to the smartphone’s appeal for users, while the U.S. government argues it is a way to charge higher prices and throttle the competition.

There is an exciting spin to the DoJ’s case against Apple. U.S. prosecutors argue that the company’s commercial triumphs – such as its securing over 65 percent of the national smartphone market – indicates an abuse of market power, effectively holding Apple’s own success against it.

The DoJ is not alone in using antitrust law to force companies to loosen control over their products. In the European Union, the European Commission and national antitrust agencies have filed several cases against companies that have successful products and generate revenue by controlling distribution channels and prices.

A recent example is Super Bock, a Portuguese beer. The brand is successful, and to maintain uniform prices among vendors, it sets a floor on the prices at which retailers can sell its products. The European Commission accepts this type of so-called “vertical restraint” in principle. But in Super Bock’s case, it decided that this constitutes cartelization, arguing that Super Bock was too successful in maintaining a wide distribution network and maintaining resale price levels.

The DoJ and the European Commission are both engaging in antitrust activism. The same trend is found in areas that formerly embraced entrepreneurial antitrust regimes, such as Switzerland and Hong Kong. Swiss antitrust enforcers take the stance that any type of price or distribution maintenance equals cartelization. In Hong Kong, antitrust policy gives China the leeway to eliminate enterprises and entrepreneurs that are considered harmful to the regime.

Activist antitrust policy is not just a problem; it is a threat. It poses a significant risk to entrepreneurialism, innovation and even to antitrust enforcement itself.

The goals of antitrust law

By doctrine and history, antitrust law (or, as it is known in Europe, competition law) has an optimistic view of market processes and a passive view of its own role. It conventionally allows markets to establish beneficial outcomes for producers and consumers. In this way, antitrust law is the opposite of regulation. Regulation means defining outcomes or constraints before market processes take place. Antitrust does the opposite; it lets market processes unfold to intervene only in cases of absolute failure.

By design, antitrust law is remedial – it cleans up if there is a mess. But one cannot know from the beginning whether there will be anything to clean up. In principle, antitrust policy strives to evaluate cases based on the merits of the specific economics at play. That means the economic process must have occurred before antitrust enforcement intervenes. This only makes the remedial stance of competition law more evident: Not all monopolies and cartels are harmful, only those that have already led (in the past) to detrimental effects.

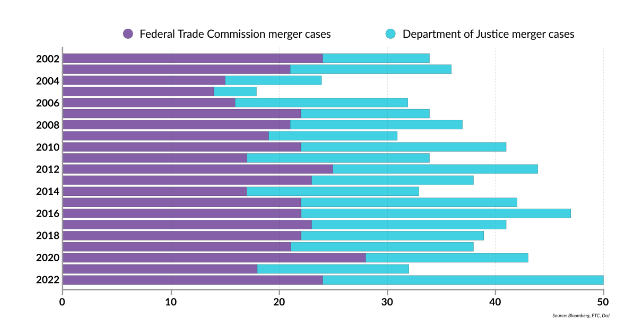

Facts & figures

U.S. antitrust merger challenges

The problem is that antitrust enforcers around the globe have departed from this economic stance and are now adopting a more activist approach. Their interventions often devolve into arbitrary exercises of bureaucratic power. Antitrust authorities, far from serving as impartial referees, frequently succumb to political pressure, industry lobbying and rent-seeking behavior – undermining the integrity and effectiveness of antitrust execution. Rather than fostering competition, antitrust agencies can inadvertently entrench incumbents, deter the entry of new competitors and distort market dynamics, leading to inefficient resource allocation and reduced consumer welfare.

When antitrust is anticompetitive

What does the DoJ’s case against Apple share with the European Commission quibble with Super Bock? Both authorities are suspicious of the companies’ success. Instead of allowing their successes to play out or be challenged by market processes, the enforcers intervene.

When used to hold down market winners, this kind of antitrust enforcement represents a misguided attempt to micromanage market outcomes and pick winners and losers based on arbitrary criteria. By penalizing firms for achieving success via superior performance and consumer satisfaction, antitrust interventions undermine the very essence of free-market entrepreneurship. Instead of allowing market forces to reward efficiency and innovation, technocrats impose artificial constraints on market winners, stifling their ability to compete.

Simply put, when antitrust agencies interpret success as a sign of abuse – and use success itself as proof of abuse – entrepreneurs have less incentive to improve their value propositions. This can only slow down innovation. Moreover, the arbitrary nature of antitrust activism creates perverse incentives for firms to engage in complicated compliance schemes, regulatory gamesmanship and litigation – diverting resources away from productive activities and innovation. This kind of antitrust policy is harmful to consumers and producers alike.

Technocratic omniscience

Why did activist antitrust enforcement develop? As in many other areas, it arose from a reliance on technocracy in its application and enforcement. Intoxicated by their belief in their own expertise, technocrats often overlook the inherent limitations of centralized decision-making and regulatory intervention. Antitrust agencies usually lack sufficient insight and expertise from the people actually exposed to market processes. Experience in entrepreneurism and management is notably absent from antitrust agencies.

Meanwhile, bureaucrats and technocrats abound. Antitrust agencies recruit directly from academia and are often consulted by professors and other researchers. There is a natural tendency to regard academic models as blueprints for market processes. This is paired with a widespread conviction that those who know the model also know more than the participants in market processes. Such illusions of omniscience blind antitrust authorities to the indeterminate and dynamic nature of market processes.

The complexity and dynamism of market processes defy attempts at top-down control. Enforcers struggle to keep pace with rapid technological advancements, shifting consumer preferences and global market integration. Technocrats’ failure to anticipate and adapt to changing market conditions underscores the folly of relying on centralized planning and regulatory mandates to dictate market outcomes.

Scenarios

Most likely: Continued antitrust activism

The most likely scenario is a continuation of activist antitrust policy. As antitrust agencies worldwide expand, so does their appetite for intervention. They equate intervention with good policy and use this equation to gain political influence.

Technological developments such as networked business models, artificial intelligence and the rise of Web 3.0 provide ample opportunities for antitrust agencies to take action. Instead of waiting for market processes to develop, enforcers will try to regulate these new developments using antitrust. The European Union’s Digital Markets Act and AI Act are just two examples of enforcers shifting the mission of antitrust policy from a remedial to a regulatory approach.

Most antitrust agencies act unchecked by the political leadership, which allows them to set out realities that are accepted or endorsed by the government. Antitrust policy is far too complicated to become the focus of any country’s leadership; if agencies maintain a narrative of “aiding consumers,” they are generally left to themselves. In cases where courts stop these agencies’ activism, the restraint is often temporary, only delaying the enforcement agenda.

This scenario results in less competition, less innovation, fewer successful companies and worse outcomes for consumers and producers. The EU is a case in point: Very little innovation within industries or in business models comes from Europe. Its citizens suffer from declining welfare, and its companies are less productive than their global competitors.

Least likely: Legal and political pivot

In the least likely scenario, courts take a robust stance on antitrust overreach, ensuring that enforcement reverts to its original, remedial modus operandi. Court rulings pushing back on regulatory activism will either make the antitrust agencies realize they have to return to their mandates or encourage political leaders to defang the authorities. With time, antitrust policy will refocus on cleaning up messes as they occur.

For this scenario to happen, it is not sufficient for activist enforcers to lose some court cases. The European Commission, for example, often loses its cases before the European Court of Justice. Beyond the individual cases, courts would have to incessantly make clear how far authorities have strayed from their mandates. Courts are reluctant to act in this way.

However, if this scenario were to materialize, it would ignite a wave of globalization, global competition and innovation. EU economies could catch up after decades of mediocrity and downward-sloping innovation rates.

Moderately likely: Antitrust activism goes global

The worst-case scenario for businesses and innovation is not at all implausible – less likely than the first scenario but still very much possible. Under this scenario, the activist antitrust approach becomes mainstream worldwide, and courts join the interventionist agenda of enforcers.

Also, EU-style regulation via antitrust becomes the global norm. Success is treated as evidence of abuse; companies are only allowed to grow if they share their proceeds with the antitrust agency – that is, with the government. The government’s grip over the economy would expand, and it could expect inflows of cash. Courts would stop pushing back against overbearing agencies and enable or endorse their actions.

Unsurprisingly, this would see a slowdown in global innovation and competition. A loss in competition and productivity, and finally in consumer welfare, would follow. This scenario makes everyone worse off – that is, everyone except the activist enforcers.

This opinion was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/tyranny-antitrust/