Using dollarization to fight (more than) inflation

Abstract

In this paper, I discuss the benefits and dangers of dollarization. Dollarization is not only a way to control inflation with chronic monetary imbalances; it is fundamentally an institutional reform that contributes (in the margin) to checking the amount of government spending. Conversely, a poor design of a dollarization reform can facilitate the government confiscation of deposits and even relaunching its domestic currency.

JEL Codes: E42, E50

Keywords: dollarization, inflation, institutional shocks

1. Introduction

Even with the recent spike due to Covid-19, inflation as a severe problem is not a significant issue anymore for most countries. In 2019, the average world inflation rate was 4.6% (excluding outliers), with 70% of the countries having inflation below 3.2%. However, some countries are unable to control their inflation rates. In 2019 (just before Covid-19) the inflation rates of Argentina, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe were 54%, 9,585.5%, and 255%, respectively.

Chronic and volatile inflation, as seen in these countries, suggests the problem is institutional. These countries need a robust institutional framework and the right political incentives to put their monetary matters in order. Institutional problems require institutional solutions. Furthermore, an institutional solution can be domestic or exogenous. A domestic institutional solution is a reform put forward by policymakers. A notable example of domestic anti-inflationary policies is the United States’ self-control of high inflation rates in the early 1980s during Volker’s tenure at the Federal Reserve.

On other occasions, when the institutional framework is seriously eroded, the domestic policy cannot create the needed credibility to put forward a permanent institutional reform. Countries such as Argentina, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe fall into this category. In terms of Nino (1992), Ocampo (2022), and Waldmann (2003, 2004), these countries suffer from institutional anomie. In this situation, not even the government follows its legislation (the rule of government replaces the rule of law).

In such extreme cases, the institutional solution must be exogenous. Countries like those of Ecuador and Zimbabwe show that eliminating the domestic currency and adopting a foreign currency effectively eradicates inflation. It is no mystery that eliminating a currency that grows out of control and replacing it with a world reserve currency, such as the U.S. dollar, will result in less inflation. However, much confusion remains on dollarization beyond its effect on inflation. This paper looks at dollarization as a means to fight inflation and other institutional shortcomings in troubled countries.

Section two offers a simple analytical framework to understand the fiscal drivers behind high inflation rates in countries with high and low institutional quality. Section three discusses the institutional and economic preconditions necessary to dollarize. Section four presents the cases of Ecuador and Zimbabwe and comments on what we can learn from their divergent paths. Section five concludes.

2. The Analytical Framework

Following a similar approach to Cachanosky et al., (2022), I’ll develop a simple analytical framework to compare different sources that can be used to finance budget deficits.

Let total deficit (D) equal the interest (i) paid on outstanding debt (B) , plus government spending (G) minus tax revenues (T) (equation 1):

D = iB + G – T 1

In a typical country with high-quality political institutions, the government finances its budget deficit with new debt (ΔB). In countries with weaker institutions, where the central bank’s independence is not guaranteed, the government can also monetize the budget deficit (ΔM), potentially leading to high, persistent, and volatile inflation (Sargent, 2013).

I categorize these countries as mid-quality political institutions. In countries with low-quality political institutions, “other” (X) measures to finance the deficit, such as confiscations and expropriations, are also possible.

The following table summarizes the above options to finance the total deficit conditional on the quality of the institutional framework. In the case of a dollarized country, the possibility of monetizing the budget deficit is unavailable.

Table 1. Deficit Financing and Quality of the Institutional Framework

Total deficit financing options Quality of the institutional framework

D = ΔB High

D = ΔB + ΔM Medium

D = ΔB + ΔM + X Low without dollarization

D = ΔB + X Low with dollarization

Given a constant, each financial source faces a different constraint and marginal electoral cost to the government. Consider first issuing debt. Unlike residents’ obligation to pay taxes, lenders are under no obligation to purchase government bonds. Rising risk premia imposes a market limit to how much debt a government can issue in the international markets. In addition, issuing domestic debt produces a crowing-out effect limiting the funds available to the private sector. The limit of how much debt the government can issue is “imposed” by the market.

Consider second the case of deficit monetization. Inflation dynamics impose one limit. Once inflation is too high, the inflation tax collected hits decreasing marginal returns (Olivera-Tanzi effect) and, in extreme cases, a monetary collapse in the form of hyperinflation. Another limit is the electoral cost of imposing high inflation on the public. Unlike bondholders’ willingness to lend, the government can sway the public’s reaction to inflation. Political leaders can persuade a median voter subject to rational ignorance (Downs, 1957) and rational irrationality (Caplan, 2007) into believing that corporate greed is the reason behind inflation or any actor other than the central bank. A typical Latin American charismatic populist leader can effectively relax the electoral cost of high inflation and seize higher levels of tax revenue.

Finally, in countries with weak republican institutions, the option of seizing funds through “other” sources (X) can have variable electoral costs to the government. As long as the leader can have the median voter side on his quest to confiscate assets from “exploitative foreign corporations,” the marginal benefits will be higher than the marginal cost of such a course of action. Iconic populist 21st-century populist leaders like the Kirchners in Argentina and Rafael Correa resorted to confiscations and expropriations on more than one occasion.

Consider now the fourth case, a dollarized country with low-quality institutions. In this case, the easy way out of the budget deficit, monetization, is not possible. Two options follow from dollarization. Either the government reduces the budget deficit or increases the debt and expropriations. It is a case-by-case empirical question of which course of action will take place in each dollarization case in a country with low institutional quality.

Dollarization is an institutional constraint (in the margin) if it binds sooner than taxes and debt when funds are needed to cover a budget deficit. If dollarization is a binding constraint to over-expanded governments, then we should observe attempts to circumvent dollarization. Ecuador and Zimbabwe show efforts to get around dollarization with different outcomes.

3. Lessons from Real World Cases: Ecuador and Zimbabwe

3.1. Lessons from Ecuador

Ecuador’s dollarization is a paradigmatic case in Latin America. It dollarized in the middle of a severe financial and economic crisis. This dollarization event is different from those observed in Panama and El Salvador. The former has been dollarized since its independence in 1904. The latter dollarized under decent economic conditions to increase international trade and reduce interest rates. But also to institutionally protect pro-market reforms in the event a new populist regime takes place.1

In the second half of the 1990s, a series of shocks and policy decisions drove Ecuador into stagflation. Between 1994 and 2000, the poverty rate climbed from 34.9% to 50%.2

In 1999 GDP fell 4.9% thanks to El Nino and the reversal in the price of commodities. The financial crises in the late 1990s contributed to the net outflow of financial capital. Besides freezing bank accounts, the government also declared the default of some of its Brady bonds. To complete a summary of the economic context at the time, the budget deficit was 5% of GDP, and government debt reached 100% of GDP.

Dollarization seems to have been the only way out of the crisis. Inflation was getting out of control, rising from 22.9% in 1995 to 52.2% in 1999. With no political support, the government had to choose between hyperinflation and major monetary reform. There were two options for monetary reform: (1) a currency board and (2) dollarization. The government discarded the currency board alternative due to the economic prospects of this monetary regime in Argentina. Dollarization, then, was the way out.3 In the words of Alfredo Arízaga (Mahuad Witt, 2021 location: 12389), Ecuador dollarized to end two lost decades, not just to get out of the current economic crisis.

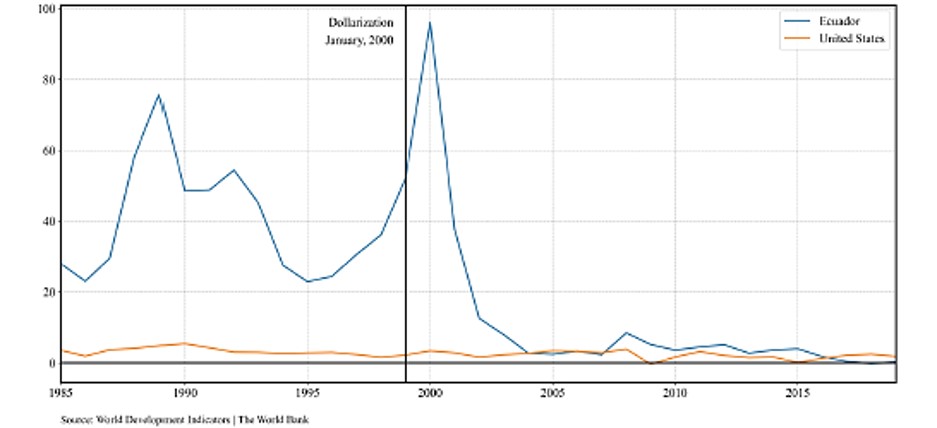

Ecuador announced its dollarization on January 9th, 2000. The impact was instantaneous. The announcement was enough to revert the drain of bank deposits and reduce interest rates. Even though in 2000, the inflation rate spiked due to (1) lags from the previous year’s exchange rate depreciation, (2) a rise in utility prices, and (3) price rounding, the effect on the inflation rate is notable. In 2001 the inflation rate fell to 37.7%, reaching 2.7% in 2003. Since then, Ecuador’s inflation rate has been similar to that of the United States (Figure 1).

On January 21st, one day after President Mahuad Witt enacted the dollarization law, he was removed from office by a military uprising. The new President, Noboa, did not only keep dollarization; he also moved forward with other needed economic reforms. Dollarization was a bottom-up process with high public opinion acceptance; no political leader dared to try to de-dollarize Ecuador openly.

Figure 1. The yearly inflation rate, Ecuador and the United States

This reduction in inflation is not a minor achievement for a country on the brink of hyperinflation and with no easy way out of its ongoing economic underperformance. Yet, dollarization was not the only reform that took place. Soon after dollarization, the government passed the Law for Ecuador’s Economic Transformation – known as Trolebús 1 and Trolebús 2. Later, Correa would revert many of the reforms that took place besides adopting the U.S. dollar.

As mentioned above, the government felt dollarization was a binding constraint, especially by Rafael Correa (2007 – 2017), who described the monetary regime as “committing monetary suicide” (as quoted in Edwards, 2019). Correa’s behavior is telling. Soon after becoming president, he mandated the creation of a liquidity fund and seized its funds. He also took possession of bonds held but the deposit insurance agency. In December 2008, he had the central bank cease the publication of its four-system balance sheet, a very transparent document showing the financial soundness of the central bank. The actual situation of the central bank and, by implication, of the financial sector became a guessing game. Correa moved on to use the central bank to seize bank reserves.

When the price of commodities started to revert in 2014, and the country’s risk premia increased, Correa announced the issuance of dinero electrónico (DE) (the first attempt to issue a central bank digital currency – CBDC). Despite the marketing campaign and tax benefits, DE failed, and Correa’s successor, Lenin Moreno, abandoned the project in 2018 (see Arauz et al., 2021)

The case of Ecuador shows that dollarization does more than put inflation under control. Even though Correa eroded Ecuador’s dollarization, he could not re-insert the sucre and avoid its institutional limits. Domingo Cavallo, former Minister of Economics of Argentina, stated that “there is no doubt” that thanks to its dollarization, Ecuador avoided reaching the “same situation as Venezuela” (Mahuad Witt, 2021 location: 319).

3.2. Lessons from Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is the only African country to experience hyperinflation, which took place under Robert Mugabe’s dictatorship (1980 – 2017). In 2007, the inflation rate reached 66,212%. In May next year, Zimbabwe issued the now famous Z$500 million bill (Zimbabwean dollar), at the time equivalent to two U.S. dollars.4 Private estimations point to a 100% daily inflation rate in November 2008. That same year real GDP fell 16%.

Figure 2. 500 million Zimbabwean dollar note – equivalent to 2 U.S. dollars when first issued

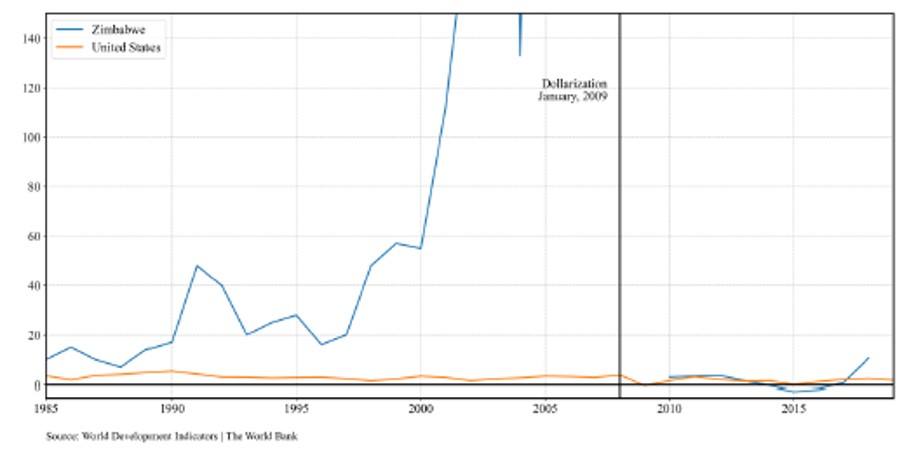

Zimbabwe’s dollarization started in February 2009. Besides the U.S. dollar, the government granted legal tender status to the currency of trade partners such as the British pound, the euro, the South African rand, and the Chinese renminbi, and banks were allowed to take deposits in any of these currencies. In 2010 the inflation rate plumbed to 3.0%. The inflation rate remained at similar levels to the U.S. until Zimbabwe de-dollarized in 2019.

Figure 3. Yearly inflation rate, Zimbabwe and the United States

Like in Ecuador, dollarization was effective in immediately stopping inflation. It gave Zimbabwe a decade of price-level stability, an unknown condition in Zimbabwe. Also similar to Ecuador, dollarization was a constraint to unsustainable budget deficits. Especially in 2016, with a budget deficit of 6% of GDP. The following year Mugabe is removed from government. The size of the budget deficit was particularly challenging for a country with a small domestic financial market and limited access to international funds. The lack of credible funding sources and the political crisis contributed to the withdrawal of bank deposits. Because of this, the government restricted U.S. dollar withdrawals from bank accounts – U.S. dollars were kept captive inside the domestic financial market.

Different from Ecuador, however, Zimbabwe de-dollarize de jure. The government also originally set the tone that dollarization was a temporary measure, setting expectations for re-introducing a domestic currency in the future. With the U.S. dollars captive in the financial market, the government announced in February 2019 a new domestic currency to be issued by the central bank, the RTGS dollar (real-time gross settlement). The newly created RTGS was used to swap bonds and in circulation. In addition, the government mandated the conversion of all financial assets and liabilities to RTGS at a 1-to-1 conversion rate with the U.S. dollar. The process of de jure de-dollarization culminated in June 2010 when the government declared RTGS the only currency with legal tender status. Despite stabilization plans and support from the International Monetary Fund, the inflation rate went from 10.6% in 2019 to 557.2% in 2020.

4. Using Dollarization to Fight (More Than) Inflation

Dollarization is efficient in fighting out-of-control inflation. Countries with high inflation, such as Ecuador and Zimbabwe, were able to converge to U.S. inflation levels through dollarization. Dollarization is a credible commitment to a reasonable money supply. However, dollarization is neither perfect nor contributes exclusively to the problem of fast-rising prices.

As Cachanosky et al. (n.d.) emphasize, dollarizing and keeping the central bank is an unnecessary risk. Government entities and the private sector can provide services other than note issuing, typically done by a central bank (Table 1). Ecuador and Zimbabwe show that the central bank facilitates how authoritarian regimes can erode the constraints imposed by a dollarization regime. Correa was able to seize bank reserves and tried to issue the dinero electrónico because he had the central bank at his disposal. Zimbabwe was able to de-dollar-ize by launching the RTGS and restricting deposit withdrawals. The existence of the central bank also facilitated this strategy.

Figure 4. Central bank roles under dollarization

Yet, Ecuador did not de-dollarize de jure. The different outcomes between Zimbabwe and Ecuador point to an important factor. The “informal” constraint of the public opinion reactions to de-dollarization attempts is an important protection against de-dollarization efforts. Technically speaking, Correa had the tools and political power to de-dollarize, but politically it would have meant the end of his presidency. With its limitations, Ecuador is still a constitutional democracy with presidential elections.

On the other hand, Zimbabwe is a failed state where the impact of public opinion is less relevant. Politically, it was less costly for Zimbabwe to de-dollarize than for Ecuador. Economically, however, de-dollarization was very costly for Zimbabwe. The inflation rate climbed to 557.2%, and real GDP fell to 6.3% in 2019.

It is possible for a government to de-dollarize de jure and avoid high economic costs. A credible abandonment of dollarization without high economic costs is possible if the government rebuilds its credibility and balances its budget. Probably a good example of this situation is the Dominican Republic. After their de-dollarization in 1947, their inflation rate remained equal to (if not lower than) the U.S. inflation rate. The problem with Ecuador and Zimbabwe is the lack of credibility in their political regimes.

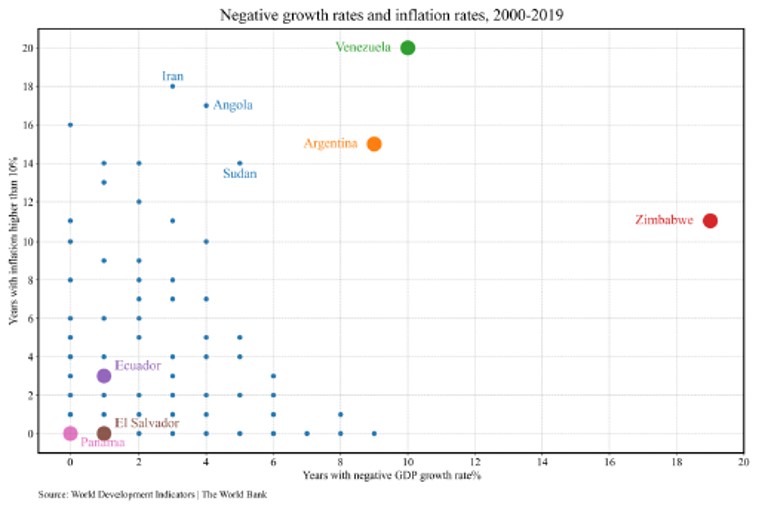

Having clarified this point, let’s return to countries where dollarization is discussed as a potential reform, such as Argentina and Venezuela. These countries suffer from institutional anomie and are not only poor performers in terms of inflation, but they also depict poor performance in terms of real output (Table 1 – replicated from Ocampo (2023)). These countries do not debate whether dollarization is the right tool to cut down inflation by a few points to regular rates; they discuss if it is the right tool to eliminate unsustainable inflation and underperforming real output. For these countries, dollarization is more than a monetary reform; it is an institutional shock whose credibility rests on its difficulty to revert by local politicians. When the institutional preconditions for standard policies and models are absent and cannot and domestic policymakers cannot provide them, they must be “imported” from a credible monetary institution.

Figure 5. Poor inflation and real output performance, 2000 – 2019

5. Conclusions

Dollarization is more than a monetary policy reform that can be used to eliminate inflation. At its core, dollarization is an institutional reform that includes credible and robust constraints on monetary policy. As a result of this combination, inflation is under control.

Real-world cases of dollarization provide a few important lessons. The first is that dollarization is effective in quickly reducing high inflation, as the case of Ecuador shows. The second one is that dollarization can be implemented in different ways. For example, it is not the same as how it works in Ecuador, El Salvador, Panama, and how it did in Zimbabwe. Finally, maintaining the central bank after dollarization is an unnecessary risk. The central bank is the door used by populist leaders to seize deposits, erode dollarization, and try to reissue a domestic currency.

Nicolás Cachanosky

Center for Free Enterprise

University of Texas at El Paso

500 West University Avenue

El Paso, TX 79968, United States

ncachanosky@utep.edu

XVII International Gottfried von Haberler Conference, Vaduz, May 12, 2023.

1 Consider the recent attempts by Nayib Bukele to displace the U.S. dollar by legally adopting bitcoin.

2 Source: The World Development Indicators (The World Bank). The poverty rate is measured as percent of population at $3.20 (2011 PPP) a day.

3 There are different accounts of who had the initiative to dollarize and how the events played out. For an insider account, see Mahuad Witt (2021). Also see Beckerman and Solimano (2002).

4 Today Z$ 500 million bills can be bought as a collectible item.

References

[1] Arauz, A., Garrat, R., & Ramos F., D. F. (2021). Dinero Electronico: The rise and fall of Ecuador’s central bank digital currency. Latin American Journal of Central Banking, 2(2), 1'10. https://doi.org/j.latcb.2021.100030 [2] Beckerman, P., & Solimano, A. (Eds.). (2002). Crisis and Dollarization in Ecuador: Stability, Growth and Social Equity. The World Bank. [3] Cachanosky, N., Ocampo, E., & Salter, A. W. (n.d.). Lessons From Dollarization in Latin America in the 21st Century. The Economists’ Voice. [4] Cachanosky, N., Salter, A. W., & Savanti, I. (2022). Can Dollarization Constrain a Populist Leader? The Case of Rafael Correa in Ecuador. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 200(August), 430–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2022.06.006 [5] Caplan, B. (2007). The Myth of the Rational Voter. Princeton University Press. [6] Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harper & Brothers. [7] Edwards, S. (2019). On Latin American Populism, and Its Echoes around the World. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.76 [8] Mahuad Witt, J. (2021). Así dolarizamos al Ecuador: Memorias de un acierto histórico en América Latina. Ariel Colombia. [9] Nino, C. S. (1992). Un País al Margen de la Ley: Estudio de la Anomia como Compo-nente del Subdesarrollo Argentino. Emece Editores. [10] Ocampo, E. (2022). Fiscal and Monetary Anomie in Argentina: A Legacy of Endemic Populism. UCEMA Documentos de Trabajo, 836. [11] Ocampo, E. (2023, February 10). ¡Si se puede dolarizar! [Blog]. Dolarización En Ar-gentina. https://dolarizacionargentina.substack.com/p/si-se-puede-dolarizar [12] Sargent, T. J. (2013). Rational Expectations and Inflation (Third). Princeton University Press. [13] Waldmann, P. (2003). El Estado Anómico. Derecho, Seguridad Pública y Vida Cotidiana en América Latina. Nueva Sociedad. [14] Waldmann, P. (2004). Transicio n Democra tica y Anomia Social en Perspectiva Com-parada. In W. L. Bernecker (Ed.), Sobre el Concepto de Estado Anómico (pp. 103–124). El Colegio de Mexico.