Digital ID: The visible and hidden implications

In recent months, various developments, surprise announcements and newly revived initiatives have sparked controversy and debate globally concerning the implications of digital identification systems. Most recently, the United Kingdom made headlines when Prime Minister Keir Starmer in late September announced a mandatory digital identification (ID) scheme. He stated that the move was aimed at curbing illegal migration and cutting red tape, while simplifying access to public services, from driving licenses and benefits to tax records.

A key part of the scheme, however, is that it aims to deter unlawful employment by making it illegal for anybody to work without a digital ID. This is the part that, predictably, has received most of the criticism, as it shifts the onus of proving one’s status and identity from the state to the individual. Critics argue that this reversal of the burden of proof introduces a sharp element of coercion to a program the government is presenting as benign. Beyond that, there are much broader implications that need to be considered, especially because this is not an issue that affects the UK alone, but instead represents a global shift.

Global uptake of digital identification

In September, voters in Switzerland were called upon to decide on a similar policy. By an extremely tight margin, they approved a voluntary electronic ID (eID) system with 50.4 percent in favor. The eID Act establishes a state-recognized digital proof of identity, building on a public beta phase launched in early 2025. A nearly identical initiative was rejected by the Swiss in a referendum in 2021, largely due to the control the legislation would have given to the private sector. This time, it will be the federal government in charge of issuing the IDs and operating the relevant systems, which seemed to sway just enough of the vote to pass the measure.

Unlike the UK version, Switzerland’s eID will be voluntary. For those who opt in, it will be linked to their smartphone for online identification and age verification to ease access to public services, or offline, to open a bank account, for example.

These are only the most recent stories of digital ID adoption. Especially in Europe, there is an abundance of prior instances. Estonia pioneered digital ID in 2014 with its e-Residency program and now in 2025, it has over 100,000 e-residents, enabling remote company formation and banking.

Most other European countries, including Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece and Spain, have also adopted digital ID schemes, mostly operating via apps that citizens download on their smartphones. Some allow access to core services like healthcare and welfare, while others extend to driving licenses and even digital passports. While many of these initiatives are voluntary, they have already become deeply engrained in citizens’ relationship with the state.

The push toward digital ID goes beyond Europe, and the West, for that matter. India has the Aadhaar system, the world’s largest biometric ID program, covering over 1.3 billion people and linking to services like welfare payments and banking. In the Arab world, the United Arab Emirates is a trailblazer with its mandatory “UAE Pass,” which is comprehensively integrated and required to access most services. Meanwhile in Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa and Eswatini are also all advancing digital ID plans.

In Asia, Singapore’s SingPass integrates facial recognition to allow access to government and financial services; the city-state has secured over 95 percent adoption as of 2022, according to World Bank data. China’s Social Credit System, although not a single unified national system as often portrayed, is by far the most controversial of all digital ID schemes. It ties digital identification to behavior monitoring and rates the “trustworthiness” of individuals and businesses, while dispensing rewards and punishments, including access to credit and the ability to travel.

Pushback: Mass non-compliance

In mid-October, thousands marched through London to express their opposition to Prime Minister Starmer’s plans. Although the details have yet to be fleshed out, according to the BBC the digital ID will include a name, date of birth, nationality or residency status and a photo. The government has also said it would “take the best aspects” of similar systems from Australia, Estonia, Denmark and India, citing easier access to private services and child benefits as well as health and education records.

The organizers of the protest, however, view the risk of a slippery slope. They state on their website: “Fear and propaganda are the sales pitch. Digital ID is the product. It is marketed as safety but built for control. The people still have a voice and a choice. Use them. If you accept digital ID now, it may be the last real choice you ever make.” Their solution is mass non-compliance. Since the prime minister’s announcement, an official petition to the government to nix its plans has already amassed almost 3 million signatures.

The core grievances and fears of those who oppose digital IDs, not just in the UK, but globally, certainly have merit. Of course, it makes a substantial difference whether the digital shift is voluntary or mandatory, and exactly what citizen information the IDs will contain. But broadly speaking, concerns over privacy, surveillance, security, government overreach and potential abuses are all valid.

Supporters of the change argue that it has already been rolled out in many countries, and therefore it has been tried and tested without any negative outcomes. However, this does not mean that the next government that inherits this power will not abuse it, nor does it shield everyone from future cyberattacks and data breaches.

ID mission creep and state misuse

It is also important to remember that most of the existing digital ID schemes do not yet encompass sensitive information, though they may easily require it later. For example, what if the government deems that if digital ID is to be used for tax purposes, perhaps citizens’ spending habits and bank account data should be monitored too? What if the scheme suffers mission creep that sees digital IDs spread from right-to-work, to right-to-vote, to right-to-travel? What if the state eventually ends up absorbing geolocation data, contacts or communications extracted from the user’s phone? It might sound far-fetched, but the UAE already used this kind of information to enforce Covid-19 lockdown restrictions.

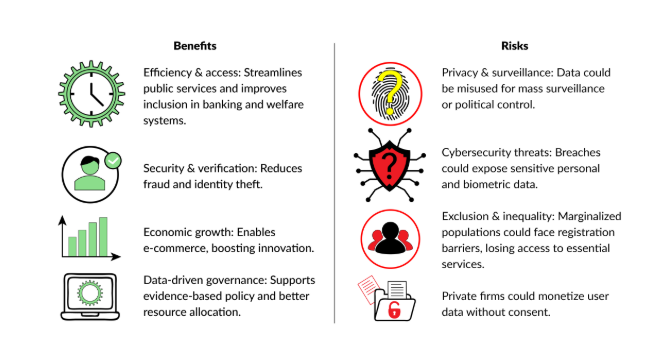

Facts & figures: Benefits and risks of digital ID

It is crucial to consider the less obvious risks going forward, to anticipate how these systems might evolve (or devolve) a few steps down the road, especially considering how new technologies like artificial intelligence can supercharge them. The economic and financial implications are particularly alarming, as digital IDs intersect with money flows, markets and the actual livelihoods of real individuals.

Take the social stratification and inequality implications for instance. Small businesses clearly face higher barriers and costs to adapt to digital verification requirements than large corporations that already have robust tech infrastructure in place. This disparity could stifle innovation and competition, eventually leading to further centralization.

On the employee side too, there is a chasm: If digital ID is required to be able to work, then only people that must work are obligated to have digital ID, meaning that the very rich or those with passive income would be able to avoid ever getting one. That is already creating a two-tier society, in which privacy and freedom from government surveillance becomes a luxury reserved for those who can afford it.

Even if data protection measures are taken seriously, if governments start accessing more types of information, it becomes easier to build multilayered profiles of an individual. For instance, location data, combined with employment or bank account information and perhaps the contacts saved in one’s phone can be used to extrapolate the person’s most likely political inclination. In other words, governments do not have to explicitly gain access to all facets of an individual’s private life to profile them to a dangerous extent – they can gather a few key data points and let statistics and AI do the rest.

Scenarios

Almost certain: Universal adoption of digital ID

It is nearly inevitable that digital ID schemes will become universally adopted sooner or later. The train has already left the station, as we can see from the many countries that have either completed the digital shift or are in the process of doing so. The only real question is whether the prevailing model will be the mandatory version, as the UK is proposing, or the voluntary one, which most governments currently have in place.

Most likely: Adoption will not be mandatory, but “encouraged”

Should the push to make digital ID mandatory be met with overwhelming public opposition, protests and non-compliance campaigns, as we have already seen in the UK, then the governments that attempt it could roll it back to a voluntary model to ensure political viability. This could delay mass adoption, but most likely not for long.

This is because even in this case, adoption could be “encouraged” or indirectly coerced, by offering various advantages and perks to those who choose to embrace the digital ID. This would look similar to the vaccine mandates during the Covid-19 crisis, which in many cases did not outright force people to get vaccinated but made their lives very difficult if they did not.

A similar approach could be adopted to get citizens on board with the digital ID. Preferential treatment when accessing public services, added burdens in accessing banking services, education or new hurdles and red tape to travel or to open a new business, could certainly push a lot of skeptics toward adoption simply for the sake of convenience.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/digital-id-implications/