China trapped in a cycle of deflation

When Xi Jinping became president in March 2013, there was widespread optimism across China. At that time, many Chinese economists held a linear viewpoint, believing that the country’s development would progress continuously. However, today, China finds itself trapped in a deflationary cycle.

Deflation occurs when weak demand leads to falling prices for goods and services, especially industrial products. Food staples are typically less affected. This price decline results in consumers and businesses refraining from purchases as they expect even lower prices in the future, which can trigger drops in wages and set the stage for a recession. China has been experiencing continuous deflation, with prices falling for six consecutive quarters. Traditionally, Beijing has responded to deflation with aggressive monetary easing and fiscal stimulus. However, since the Covid-19 pandemic, the government has taken a more cautious approach to prevent a rise in debt.

Facts & figures: China’s persistent deflation

The GDP deflator, or implicit price deflator, is a measure of inflation that compares the value of goods and services produced in a specific year at current prices to the prices from a base year. Source: Bloomberg

From optimism to hard reality

Professor Justin Yifu Lin from Peking University represents linear thinking in China. In 2015, he predicted that China would reach the “high-income stage” in 2025. The World Bank defines a high-income economy as one with a gross national income (GNI) per capita exceeding $14,005 in 2023. Between 1978 and 1998, China experienced its low-income stage, with GNI rising from $190 to $820. The lower-middle-income stage lasted from 1999 to 2009, followed by the upper-middle-income stage from 2010 to 2023.

Despite Professor Lin’s optimistic predictions, harsh realities have unfolded. President Xi’s strict zero-Covid strategy and ineffective economic policies have decisively led to a significant contraction in China’s economy. The decline is alarming, especially since officials stated in 2017 that China’s middle-income population had surpassed 400 million. Furthermore, the Xi administration unequivocally declared that China had successfully eliminated poverty in 2020.

On the contrary, a December report revealed troubling findings. Professor Li Shi, the director of the Institute of Sharing and Development at Zhejiang University, conducted research indicating that approximately 65 percent of the country’s population does not meet the middle-income threshold. This translates to around 900 million individuals living in low-income conditions, which Professor Li defines as a monthly income of less than 3,000 yuan (approximately $412).

Professor Li highlights a significant income disparity among these 900 million people, noting that some in the group earn amounts nearing the middle-income level while others remain in relative poverty. If we consider individuals in China whose “actual disposable income is less than 3,000 yuan” – including those who may seem to earn more due to ongoing mortgage and car loan payments – the reality is that many struggle to get by on incomes below this threshold. As a result, the total number of people facing such financial struggles could be even more significant than previously estimated.

Professor Li’s forecast closely aligns with the statement made by former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in 2020. At that time, Premier Li claimed that 600 million people in China, or 40 percent of the population, were earning a monthly income of just 1,000 yuan (approximately $137). China’s National Bureau of Statistics later remarked that this figure aligns with the nation’s fundamental economic conditions. Given this context, one must then also consider the economic downturn following the pandemic, which has led countless businesses across the country to either shut their doors, lay off employees or slash salaries.

Challenges in economic reporting

In line with President Xi’s principle of sharing “good stories of China,” many official reports portray the situation only in a positive way. For instance, authorities recently revealed through the 2023 Personal Tax Settlement Report that over 600 million ultra-low-income earners make less than 3,500 yuan monthly. The same applies to China’s official gross domestic product (GDP).

In this context, two Chinese economists have surfaced with claims that contest official data and have since experienced suppression by the authorities. One of them, Gao Shanwen, who serves as the chief economist at SDIC Securities and previously held a position at China’s central bank, has suggested that China’s GDP “is overestimated by three percentage points per year and 10 percentage points cumulatively” for the period 2021-2023. His assertions stem from a noticeable disconnect between the reported figures for growth, employment, consumption and investment. Mr. Gao pointed out that the current level of unemployment starkly contrasts with the official economic growth rates, forecasting that there are roughly 47 million fewer new jobs than expected.

Adding to this critical perspective, Fu Peng, an economist at Northeast Securities, recently highlighted that weak consumer spending is primarily due to declining real estate prices. This drop has caused negative equity for some middle-class homeowners. As layoffs and pay cuts create a sense of panic among the middle class, many are now significantly cutting back on their spending.

Facts & figures: Household contribution to real GDP growth, year-on-year percentage change

This decline in purchasing power is not a short-term phenomenon but a structural shift. Mr. Fu is skeptical of the current government’s ability to alter this structural problem. He says, “Due to the depth of the problem, it has been difficult for the government to reverse the rapid shrinkage of the middle class through measures to stimulate the economy by adding leverage.” Mr. Fu’s analysis holds weight, given that China’s real estate sector represents 70 percent of the nation’s household wealth. If the crisis persists, it could erode both consumer and business confidence.

China’s economy underperformed last year, and despite introducing official relief measures, the desired results have yet to materialize. The real estate crisis has intensified, local government debt remains high, consumer spending is weak, exports are underwhelming and there is a noticeable outflow of companies and capital from the country. While the central government has implemented various strategies to boost economic growth, these stimulus measures are no longer as effective as they were in 2008.

Xi Jinping’s failed endeavor in structural change

There are three traditional engines of economic growth: infrastructure investment, real estate and exports. In recent years, the first two of these engines have significantly stagnated. The real estate sector, which contributes around 20 percent to GDP, is no longer the driving force it once was; instead, it risks becoming a drag on economic progress. Meanwhile, infrastructure investment, accounting for approximately 24 percent of GDP, can no longer be pursued as freely as before due to local governments’ substantial debt burdens.

President Xi hopes exports will rejuvenate China’s economy. Since 2020, he has been striving for a structural transformation, aiming to shift away from traditional economic drivers like real estate and domestic consumption. Instead, he has focused on developing high-tech industries and exporting products in sectors such as electric vehicles, car batteries and solar panels. Respectively, China’s exports have surged. However, his approach to economic diplomacy has faced significant pushback from other countries.

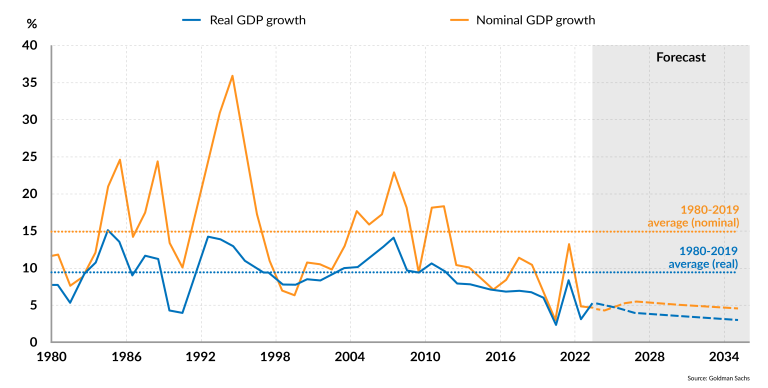

Facts & figures: China GDP growth, year-on-year percentage change

Government initiatives for economic recovery

As China’s economy experiences a significant decline, the challenges of daily life for young and middle-aged citizens are escalating to the point that some individuals struggle to afford even their next meal. The sharp rise in foreclosures, the increasing number of homeless people and the growing trend of indiscriminate victimization all highlight the troubling issue of so-called “returning to collective poverty.” The central government is aware of these pressing concerns and expressed that they require extraordinary urgency during the Central Economic Work Conference held in December.

President Xi committed to improving conditions for middle- and low-income groups, highlighting plans to raise basic pensions for retirees and urban and rural residents. He also pledged to increase financial subsidies for medical insurance and enhance efforts to protect people’s livelihoods, aiming to improve their sense of achievement, happiness and security.

Key decisions from the recent economic conference included plans to increase the fiscal deficit ratio in 2025, issue more ultra-long-term treasury bonds and cut interest rates to ensure abundant liquidity. Policymakers advanced a “moderately loose monetary policy,” signaling China’s financial strategy shift toward a more accommodative approach in 2025. The fiscal deficit target could be raised to 4 percent of GDP from 3 percent. The People’s Bank of China is expected to ease monetary policy by buying treasury bonds, facilitating increased government borrowing to stimulate the economy. Additionally, a 40-basis point cut in the policy rate is possible, which would be the largest reduction since 2016. Currently, the Chinese central bank’s benchmark interest rate is 3.1 percent.

Despite announcements highlighting “increasing government spending,” there is insufficient emphasis on “boosting consumer spending” to drive overall consumption. Up to this point, President Xi has focused more on his concept of “new productivity” through manufacturing than on prioritizing improvements in people’s quality of life. The central government seems more inclined to continue allocating resources toward manufacturing initiatives − despite global pushback against the country’s perceived dumping practices amid its manufacturing overcapacity − instead of addressing the need to increase citizens’ incomes. Ultimately, President Xi’s pledges could be little more than an open-ended ideal, rather than a concrete commitment.

Scenarios

Very likely: China’s deflation will not bottom out in 2025

Recent economic data indicate that China’s economy is likely to remain trapped in a deflationary cycle for an additional two years. The weaker-than-expected Consumer Price Index and Industrial Producer Price Index highlight this ongoing deflationary trend, likely worsening already sluggish domestic demand. China’s deflation is creating a vicious cycle, resulting in higher unemployment and reduced consumer willingness to spend as people anticipate lower future prices. To effectively address the issue, deflation cannot be solved merely by printing more money; it requires a holistic strategy.

It seems unlikely that President Xi will alter his longstanding habits. He tends to place excessive emphasis on boosting the capabilities of the high-tech manufacturing sector, particularly within state-owned enterprises, and on government intervention. This top-down focus often comes at the expense of creating a supportive environment for private enterprises and providing targeted assistance to the population regarding income. Additionally, support for the service sector is often overlooked.

The greater concern among the economic community in China and globally is whether the country’s real estate crisis matches the property bubbles experienced elsewhere. If it does, this suggests that China faces a cyclical issue: It will eventually hit rock bottom and recover. The key question now is when that inflection point for recovery will happen. One thing is clear: China’s deflation is unlikely to reach its lowest point this year.

Likely: China to take advantage of Trump’s unpredictability

President Donald Trump has indicated plans to implement a 10 percent import tariff on goods brought into the United States, with a steep 60 percent tariff explicitly aimed at Chinese imports. Additionally, the new Trump administration is debating the potential removal of China’s permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status, which has granted China the most-favored-nation treatment since it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. This change could significantly hinder Chinese exports from becoming a key driver of the country’s future economic growth.

Revoking China’s PNTR status is expected to have a more severe impact on China than on the U.S. A simulation by the Institute for International Economics of how stripping China of that status would affect economic development predicted a 0.6 percent decline in China’s GDP in 2025, while the U.S. would only see a 0.1 percent drop. Additionally, the U.S., European Union and even some BRICS countries have started boycotts or restrictions on Chinese dumping in addition to tariffs. Given these circumstances, China’s economy is much weaker today than when the last trade war erupted.

However, some observers overlook a key point: President Trump’s unpredictability in trade policy could work to China’s advantage. His approach raises concerns that Beijing may take advantage of this unpredictability and take advantage of his close relationship with Elon Musk, who has significant investments in China.

Unlikely: Collapse of the Chinese economy

It is important to note that while China’s economy faces significant internal challenges and intense external pressures, it is not on the brink of collapse just yet. The country still has several advantages. During the first three quarters of 2024, the value added by industries above the designated scale grew by 5.8 percent compared to the previous year. Specifically, the value added from high-tech manufacturing and equipment manufacturing industries in this category saw annual increases of 9.1 percent and 7.5 percent, respectively. This demonstrates that critical sectors are thriving despite the broader challenges.

The recently released Global Innovation Index Report 2024, published by the World Intellectual Property Organization, highlighted that China has become one of the fastest-growing economies in terms of innovation over the past decade. For example, advancements in electric vehicles and renewable energy technologies have positioned China as a leader in these sectors. Crucially, this surge is driven by the economy being a vital lifeline for the Chinese Communist Party. As a result, President Xi may feel compelled to respond to economic demands, even if only as a temporary measure.

This report was originally published here: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-deflation/