A credibility dilemma in Milei’s economic plan

Despite swiftly balancing the budget and lowering the inflation rate two months in a row, concerns continue to grow around Milei’s economic plan. Why are new positive economic results faced with increasing uncertainty?

Inflation and the “Plan Platita”

Indeed, as the graph below shows, the monthly CPI inflation rate rose from 12.8% in November to 25.5% in December and then fell to 13.2% in February. The core-CPI shows a similar behavior.

Now, this is not to say that Milei’s government is doing nothing to reduce inflation. There have been no transfers from the central bank to the Treasury under his administration (which has been the case since October 2023), and the monetary base contracted by 3.5% in February (it also contracted by 1.8% in February 2023 under the Kirchner administration). If this austerity continues, inflation is indeed expected to keep falling; but so is economic activity.

Will inflation continue to fall once the plan platita effect fully disappears? It wouldn’t be the first time that a policy aimed to control inflation fails: Not that long ago, Macri’s government implemented the popular inflation targeting framework, which failed within two years and inflation soared to new high levels. This question of mid-term sustainability leads to the main issue behind the credibility of his economic plan. Are the fiscal results credible?

Luis Caputo, Milei’s Minister of Economics, has shown primary and financial surpluses as early as January (Milei’s presidency started on December 10). Inflation expectations depend on what is expected to happen to the budget in the months to come. It is natural, then, to ask whether the observed surpluses are sustainable in the months ahead.

Answering this question requires looking at two things. First, how was the fiscal surplus achieved in January? Second, what is the expected behavior of revenues and expenditures?

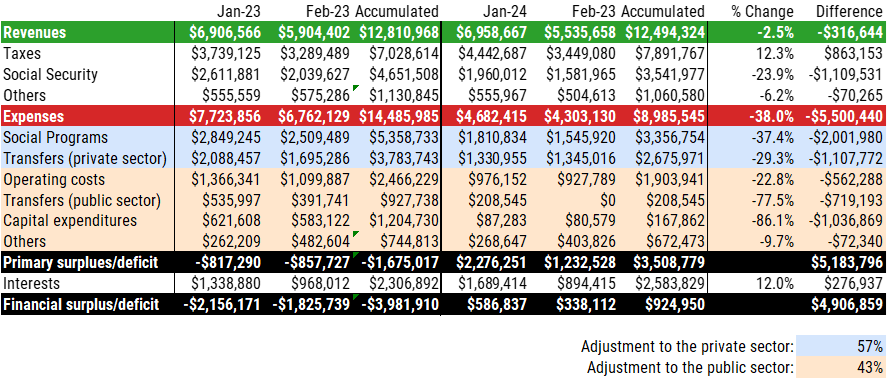

The information for the first question is included in the table below, which shows its values in constant terms (February 2024). In real and accumulated terms, fiscal revenues decreased 2.5%, while expenses collapsed by 38%. Where is spending being cut the most? Numbers show that 57% of the adjustment falls on the shoulders of the private sector, while the remaining 43% falls on the government. Contrary to Milei’s repeated statements, most of the austerity is being borne by households and the private sector, whose patience limit is unknown.1 Some of these spending cuts are achieved by postponing transfers and payments to a future month. Accrued accounting shows that in February the government had a financial deficit (not shown in the table).

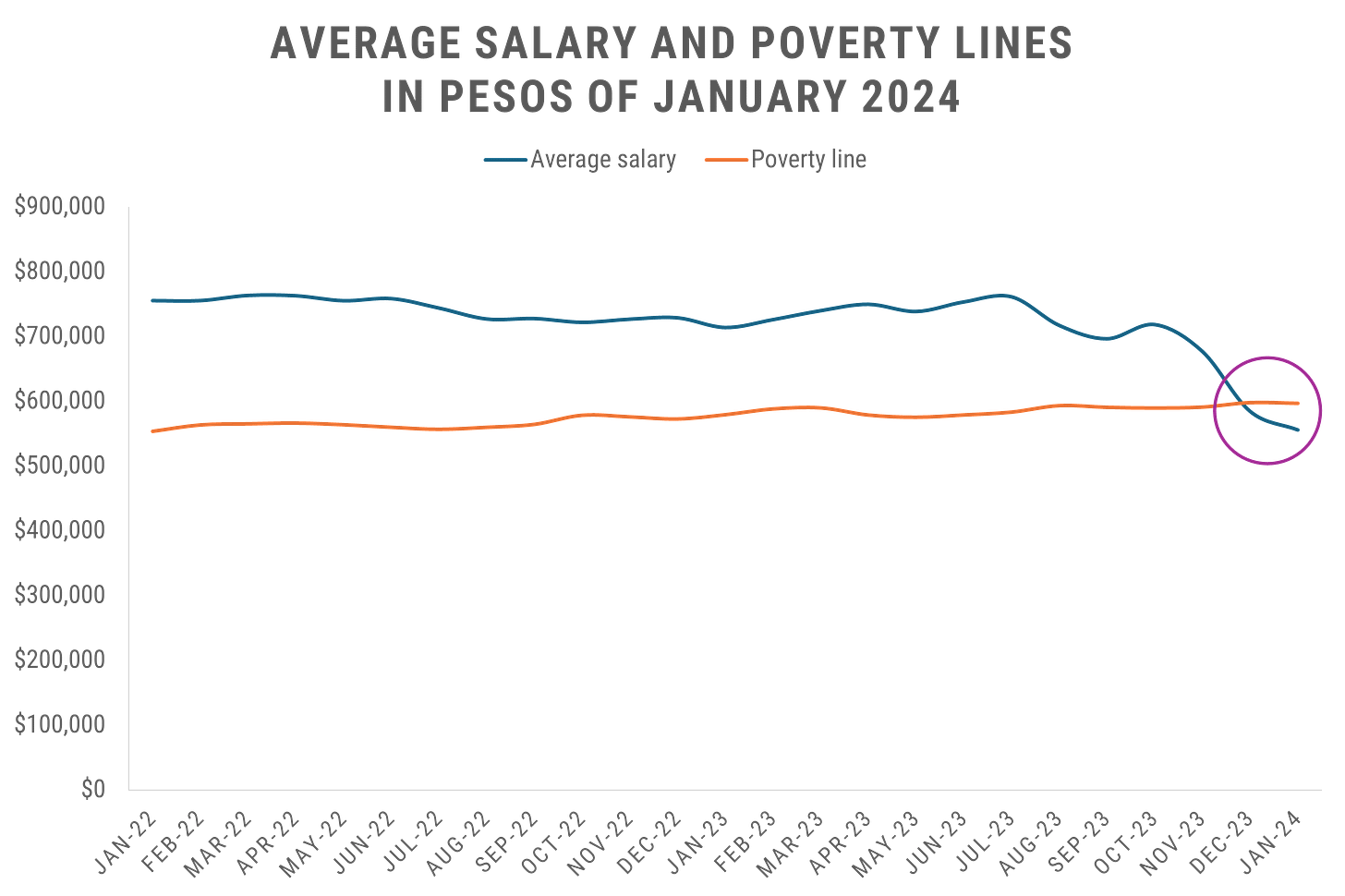

Is this sustainable? Can Milei and Caputo continue to put this level of pressure on the already suffering households? There is no data yet for January, but just in December, real salaries in the (registered) private sector fell by -11.5% and 3.7% contraction in the monthly economic activity estimator. A report by IDESA shows that retirement income levels are as low as they were during the 2001 crisis. Worrisome, Empiria Consultores shows that the average salary is now below the poverty rate (figure below). Of course, I’m not saying all of this is Milei’s fault, who received a destroyed economy, but this is the economic and social situation upon which he is adding even more pressure.

It may be the case that there is no way around adjusting the private sector. But even if that is the case, it remains a fact that it is unclear whether this situation is sustainable. It may also be the case that Milei is working towards a structural fiscal reform and that his debasement is just temporary, but the structural reform is still to be seen, leading to the second issue of the future expected behavior of revenues and expenses.

Milei is trying to have Congress endorse his necessity and urgency decree and his omnibus law. These two major pieces of legislation should produce two effects. One is a rise in tax revenues. The other one is an expected positive productivity shock by deregulating the economy and the labor market. However, Milei has only faced setbacks in Congress and in the judiciary, which suspended the labor reform chapters in his necessity and urgency decree. The increasing animosity with Vice President Victoria Villaruel does not help. Similarly, his openly aggressive behavior towards those legislators who hold the votes he needs only increases the level of uncertainty.

The legislative constraint should not be ignored.2 Before the elections, it was expected that he would be politically weak in Congress, given his political party only has a small number of seats. After the election, this expectation is now confirmed. It is only natural to see market actors feeling uncertain about the sustainability of the fiscal results observed so far not only because of the legislative defeats but also because of Milei’s reactions (not conducent to build political agreements). And if there is uncertainty about the fiscal results, there is uncertainty about future inflation. To help anchor inflation expectations, the government promised to observe a 2% crawling peg. However, if there is uncertainty about future inflation, then there is uncertainty about the sustainability of the 2% crawling peg as well.

Back to inflation: Strong and weak shocks

Disinflation is taking place through adjusting aggregate demand, not through an expansion of aggregate supply. It is possible to disinflate and grow at the same time in an economic context similar to that of Argentina. We can observe this combination taking place when Ecuador dollarized in 2000 and when Argentina imposed its convertibility in 1991.

This is one (not the only) argument in favor of dollarization in Argentina: Allow for an economic expansion while executing an aggressive fiscal adjustment and avoid the political cost of imposing an aggressive adjustment on households and economic activity. If political capital is lost due to the heavyweight imposed on the private sector, then the much-needed reforms will not take place or will be halted mid-way. Dollarization is a strong positive shock to expectations, while the current plan is a weak positive (and potentially unstable) shock to expectations.

In summary

In summary, the success of Milei’s plan rests on an economic plan sensitive to uncertainty over its sustainability. This uncertainty stems from the fiscal adjustment falling mostly on the private sector and a sequence of (not surprising) legislative failures. Additionally, the more aggressively Milei’s government fights inflation, the more pressure it puts on households. But going easy on the fiscal budget means compromising the disinflation process. In the first case, the plan may be unsustainable due to loss of political support. In the second case, the plan may become unsustainable if the 2% crawling peg is not enough to keep the exchange rate market stable.

This situation can certainly be reversed, and Milei’s plan can succeed in improving the country’s economy. No one is denying this, certainly not me. The point of this post is to understand the current uncertainty dilemma and why this can become detrimental to Milei and Caputo’s plan.

This report was originally published here: https://economicorder.substack.com/p/a-credibility-dilemma-in-mileis-economic?utm_campaign=email-half-post&r=as625&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email