3rd Award in Vernon Smith Prize 2024

(1/2 ex aequo)

Is education a public or a private good? Who gains from being educated?

Olivia Liane Opitz

ABSTRACT

This article examines whether education should be considered a private or public good and analyses the impact of both approaches on individuals and society. An equitable and accessible education system promotes social cohesion, economic stability and innovation. At the same time, individuals benefit from personal freedom and the opportunity to use their knowledge in a self-determined way. Moreover, education is a global good that enables knowledge transfer and international cooperation. A hybrid approach that combines public and private investment maximizes individual and societal benefits and improves access and quality of education worldwide.

Introduction

When I decided to take part in this competition, I started by forming my own opinion on the subject and deciding whether education is more of a private or a public good for me. Next, I read through various scientific databases as well as grey literature to get a better overview. However, an elementary question did not occur to me until much later. As I consider this question to be fundamental to this debate, I would like to address it right at the beginning of my article. The question is: What is education actually?

One definition of education that really appealed to me comes from the Federal Agency for Civic Education (n.d.). According to this, education is much more than school,

training or reading information. Rather, in addition to school, education is understood here as a process of personal development, practical and social learning, as well as one’s own freedom and the usability of the education acquired. I like this definition so much because it sees education as being detached from the school or university context and regards it as something very human and natural – something that is equally available to all people. (Possibly add Heintze’s definition p. 113). With this in mind, I would now like to address the question of whether education can be seen as a private or a public good.

In today’s society, education is officially proclaimed to be a public good that is equally accessible to all people, regardless of social status and background. This was not always the case. Especially for the emerging society of the 19th and 20th centuries, a higher education contributed significantly to one’s own identity and the enjoyment of a school and university education was seen as a status symbol. Education provided the opportunity to escape from feudal patterns of thought and behaviour and gave its owner a certain freedom and independence (Appelt & Reiterer, 2004). To a certain extent, this is still the case today, although the standard and degree of education as a social status symbol has risen. While a basic school education, a high school diploma, perhaps even a bachelor’s degree is now possible for all motivated students, higher educational qualifications such as a master’s degree, a doctorate and particularly demanding and time-consuming subjects such as medicine or law still indicate a privileged parental home.

Those with a good educational qualification have better chances of a high income, a high social status, opportunities and freedom in life (source). In this sense, the private

individual always benefits from their own education. But what about the contribution to society? A society that produces many intelligent and well-educated citizens is indirectly investing in the stability of its own economy and its competitiveness (Musgrave, 1956/1957). Addressing this topic is therefore of such great relevance, as education, particularly in a meritocracy, can be a social policy that determines the life chances of individuals (Appelt & Reiterer, 2004). In many cases, this even has positive effects on physical and mental health, life satisfaction, income, social integration and recognition, social responsibility and personal resilience (OECD, 2018; Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2006; Oreopoulos & Salvanes, 2011; Putnam, 2000; Dee, 2004; Heckman & Kautz, 2012). Furthermore, in a society with increasing social disparities, the question arises as to what contribution education makes in an increasingly privatised education system (source).

Characteristics of Public and Private Good:

The question of whether education is a private or public good can be approached in different ways. On the one hand, the financial question arises in this context, which deals with the extent to which the education system and access to it is dependent on the family’s financial resources nowadays.

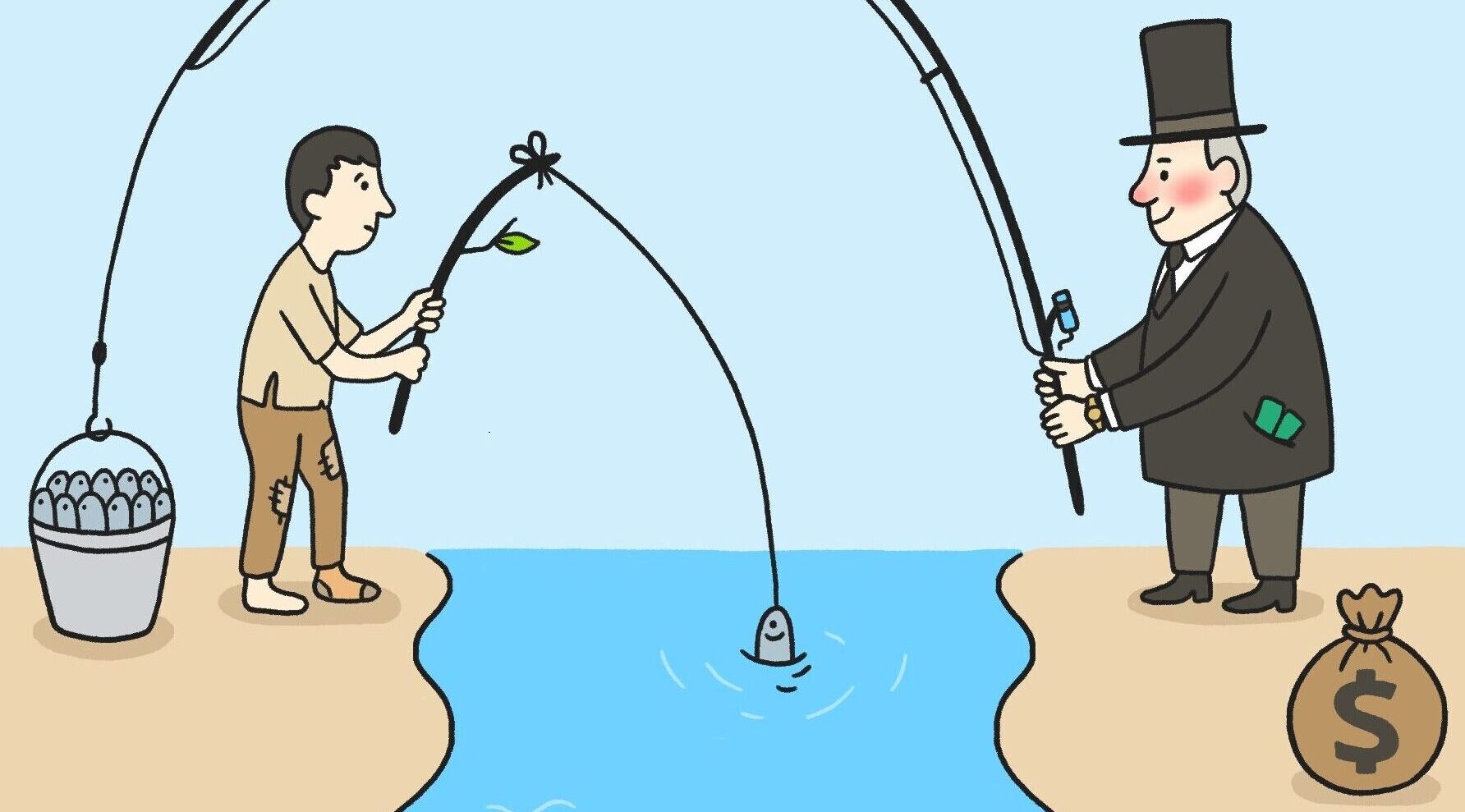

Another possibility, however, would be to find out who ultimately benefits most from education. Is it the individual private person who receives social recognition, a higher level of financial resources and opportunities through a good education, or is it the state and society that benefits from the knowledge spillover of well-educated citizens?

Samuelson (1954) addressed the question of what distinguishes public from private goods early on. He argues that public goods are neither rivalling nor exclusive. If applied to the education system, this definition would hardly apply, as the quality of education is heavily dependent on the financial resources of the family and its access is rivalling in the sense that there are only a limited number of (good) school and university places, which are preferentially allocated to pupils and students with either good grades or good financial resources. Even if it is not clear from his work that education is a private good, as he also brings the idea of a hybrid and quasi-public approach to the table, according to which basic education should be provided publicly while higher levels of education should be supported by private funds, the tendency of this argument suggests that education as a whole cannot be understood as a purely public good.

Elinor Ostrom suggests that education should be collaborative and locally flexible in order to maximise positive externalities (Ostrom, 2005). Such a sustainable approach promotes participation, but could compromise the comparability of qualifications, which should remain at a standardised level. Richard Musgrave therefore favours hybrid funding that combines public and private funding to ensure social inclusion and economic stability (Musgrave, 1959). This model can expand access to education but continues to pose challenges in terms of fairness and resource equity (Samuelson, 1954; Ostrom, 2005; Musgrave, 1959).

Arguments for Treating Education as a Private Good

This small excerpt of academic perspectives on this discourse shows that it is not so easy to view education as completely private or public, as there are so many different aspects to consider. However, this is only theory. However, a look at the reality of the German and Austrian education system shows that there is a clear gap between the winners and losers of the education system, which is widening (Thöne, 2012). Among other things, this can be attributed to the decreasing number of public educational institutions and the simultaneous increase in private ones. This fact in itself would not be a cause for concern if the conclusion could be drawn that society is increasingly affluent and more willing than before to invest more money in their children’s education. While this may be true to a certain extent, it should not be forgotten that this can never apply to the entire population and that the increasing privatisation of individual education systems excludes this socially weaker section of the population. This fact alone would be enough to recognise that education can by no means be defined as a purely public good, but there are many other aspects that can support this thesis.

If you consider, for example, the fact that public schools and universities generally offer a far greater number of additional programmes, ranging from language and sports courses to additional qualifications and internship opportunities, which give students the opportunity to establish themselves in privileged circles in the world of work at an early stage, you quickly realise that the type of education a young person receives can play a decisive role in determining where they later establish themselves in society. However, the additional programmes offered by public schools are not the only plus point. Private educational institutions also have a higher number of teachers spread over a smaller number of pupils, which means that individual pupils receive more individualised support, which in turn greatly benefits the performance of the pupils and the quality of teaching. Another advantage of public educational institutions is their greater autonomy and flexibility in designing the curriculum and type of education (Lubienski & Lubienski, 2014). Increasing privatisation should therefore be viewed critically insofar as the associated inequality jeopardises educational equity within society. Due to the selectivity of pupils and the financial support of parents, private educational institutions enjoy advantages that can hardly be offered by public representatives. In fact, studies have shown that pupils who have attended a public school often achieve better academic results and aspire to higher educational qualifications than pupils who have attended a public school. However, this is not only due to the school, but also to the socio-economic background of the students (Bundeszentrale für politische

Bildung, 2023).

With regard to the question of whether society or the state or the private individual benefits more from education, it could also be argued that an educated private individual can not only enjoy the aforementioned advantages of a good education, which has a positive impact on their life, but that they are also able to decide freely at any time whether and how they want to use the knowledge they have acquired for the benefit of society. This consideration would also support the thesis that education can be seen as a private good to a certain extent in terms of profit.

Government Support and Positive External Effects of Education

But what about the other side of the coin? What are the arguments in favour of considering education as a public good?

Education as a public good not only strengthens social justice, but is also a strategic investment in the economic future of the state. A comprehensively educated population increases the innovative strength and competitiveness of the national economy by producing a more qualified labour force and promoting entrepreneurial potential (Dee, 2004). Musgrave emphasises that state-funded education can stabilise long-term economic growth and reduce dependence on social benefits. Thus, through high public spending on education, an equitable education policy creates not only social benefits but also economic efficiency and resilience (Musgrave, 1959).

If we want to delve deeper into the question of social and state profit, we could ask ourselves whether the entire education system and the subsequent world of work are possibly geared towards serving economic growth and the good of the state and society. Through a standardized and public education system, values, ways of thinking and perspectives could be imparted to young people in the interests of the latter, which would develop them into productive, intelligent citizens. Although a high level of intelligence is desirable, a critical and independent way of thinking is not, which would like to break out of a smoothly running social machine and free itself from it. Is it not the case that a higher level of education also opens up better career prospects, which in most cases go hand in hand with greater responsibility, influence and the right to have a say in public affairs in addition to better pay? A promotion to a higher position is often accompanied by more intensive and longer working hours, which again benefits the state and society. The individuals concerned rarely ask themselves whether this makes them happier, as they are often blinded by a high salary and social recognition. Time for leisure activities, friends and family could be neglected – but at what cost?

Analysis of the German Education System: Inequality and Access Barriers

The increasing privatisation of the education system, especially in Germany, is exacerbating the social divide. Private educational institutions tend to attract more affluent

families, which can lead to an elite educational class and social inequality. This development creates financial hurdles that make access difficult for young people from low-income households, as fees and additional costs are incurred. From the point at which families with a lower income are unable to overcome this financial barrier, quality educational opportunities remain reserved for socially disadvantaged children, which again increases the already existing inequalities (Appelt & Reiterer, 2004). But why does the state not intervene in this inequality, even though it sells education as a human right?

The state benefits from the increasing privatisation of education, which is accompanied by higher cost sharing by parents, as the private institutions cover a large part of

the costs themselves in this way. This reduces the burden on the public education budget by shifting the funding to the families who are able to pay for a good education for their children (Appelt & Reiterer, 2004). The budget can thus be invested in the education system in a different way – for example, in the financing of public educational institutions (Lubienski & Lubienski, 2014).

While basic school education is still adequately supported by the state in most cases, equal opportunities at higher levels of education such as university and higher education are already declining significantly. Particularly in intensive and time-consuming study programmes such as medicine or law, where a part-time job can severely impair academic performance, teenagers and young adults from socio-economically disadvantaged families are automatically excluded. Although study grants and scholarships are available, the funding is far from sufficient to cover basic living costs, especially against the backdrop of rising rent and food prices, and scholarship places are limited and in most cases linked to outstanding performance. This can put students under additional stress on top of an already heavy workload. However, these subjects in particular are known for particularly good salary prospects – so the vicious circle is increasingly unfolding. In conclusion, education can be considered neither entirely a private nor a public good, as its benefits enrich both the individual and society. Equitable access to education promotes social cohesion, democratic participation and economic stability, thus strengthening the state and society (Musgrave, 1959). At the same time, individuals benefit from their education through higher incomes,

personal freedom and the opportunity to decide for themselves how they want to use their knowledge (Samuelson, 1954). Education as a global good also contributes to the international dissemination of knowledge, innovation and co-operation. A hybrid model that combines public investment and private contributions provides a fair basis for maximising individual and societal benefits while promoting global educational quality and access (Ostrom, 2005; Lubienski & Lubienski, 2014).

This view emphasises education as a tool for personal fulfilment and global development, which requires a fair and inclusive system to fully exploit the dual values of education for the benefit of individuals, society and the global economy.

Olivia Opitz studied Geography BSc University of Vienna and International Health & Social Management at MCI Innsbruck. Ambitious, helpful and professional are the qualities that best describe her attitude to work. She speaks Germaan, English and Spanish.

Bibliography

Appelt, W., & Reiterer, E. (2004). Ist Bildung ein öffentliches Gut? Zeitschrift für internationale Bildungsforschung und Entwicklungspädagogik, 27(3), 4–8. https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2014/9281/pdf/ZEP_3_2004_Appelt_Reiterer_Ist_Bildung_ ein_oeffentliches.pdf

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. (2023, 15. Mai). Privatschulen sind besser als öffentliche Schulen. Stimmt’s? https://www.bpb.de/themen/bildung/dossier- bildung/522257/privatschulen-sind-besser-als-oeffentliche-schulen-stimmt-s/

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. (n.d.). Bildung: Begriffsbestimmungen. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Abgerufen am 17. November 2024, von https://www.bpb.de/themen/bildung/dossier-bildung/503718/bildung-begriffsbestimmungen/

Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence (NBER Working Paper No. 12352). National Bureau of Economic Research.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w12352

Dee, T. S. (2004). Are there civic returns to education? Journal of Public Economics, 88(9-10), 1697–1720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.11.002

Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. (n.d.). Entwicklung der Löhne in Deutschland: Trends und Analysen. Abgerufen am 17. November 2024, von https://www.boeckler.de/pdf_fof/97302.pdf

Heckman, J. J., & Kautz, T. (2012). Hard Evidence on Soft Skills. Labour Economics, 19(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014

Lubienski, C., & Lubienski, S. T. (2014). The Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private Schools. University of Chicago Press.

Musgrave, R. A. (1956/1957). A multiple theory of budget determination. FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, 17(3), 333–343. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40909134

Musgrave, R. A. (1959). The Theory of Public Finance: A Study in Public Economy. McGraw-Hill.

OECD. (2018). Education at a Glance 2018: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2018-en

Oreopoulos, P., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: The Nonpecuniary Benefits of Schooling. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1), 159–184. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.1.159

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36(4), 387–389.

Thöne, U. (2012, 13. August). Bildung als öffentliches Gut. Gegenblende. Abgerufen von https://gegenblende.dgb.de/artikel/++co++c9cb31ee-e536-11e1-adc0-52540066f352